On June 16, 1944, George Stinney, a fourteen-year-old black boy, was executed by the state of South Carolina for the murder of two white girls. George was so short he had to carry a Bible to use as a booster seat when sitting in the electric chair. He was so young the death mask would not fit his face. He took five full minutes to die, the mask slipping off to show his eyes melting, his body convulsing.

There was no evidence that George had committed the murders. There were no actual witnesses to the murders—in fact, George had an alibi for the whole day in question. The “confession,” which George denied having made and which had not been recorded or written down, was the fabrication of three white police officers. But after a single day trial, an all-white male jury returned a conviction and death sentence for the fourteen-year-old boy in less than twenty minutes. George’s family had been run out of town by its white citizens so that he did not even have the comfort of his mother’s arms in the days he was imprisoned before his one day trial and ensuing execution.

A few days ago, on December 17, 2014, the state of South Carolina overturned this conviction as wrongful and unjust.

On November 22, 2014, Tamir Rice, a young twelve-year-old black boy was playing in the park in Cleveland, Ohio. Police arrived and immediately opened fire on Tamir. In the minutes that the twelve-year-old boy was bleeding out onto the pavement, the shooting officers did not deign to attempt CPR and save his life. Tamir Rice died at the hospital a few hours later.

One cannot avoid the similarities in the cases of George and Tamir. Both black boys, both executed by the state without cause. One was given the farce of a “trial,” the other was not. We have regressed it seems, from allowing even that when it comes to black boys.

Tamir Rice’s shooting happened two days before a grand jury decided not to indict another white police officer for shooting another unarmed black boy named Mike Brown six times. I couldn’t process it. I understand this is what is called shock. I was numb. The only conscious thought I had was to love my two-year-old baby boy, love every minute with him because I did not know how many days until he, too, could be shot down to contain the “threat of his skin;” Aiyana Jones, a black girl, was seven and also unarmed when white police officers, again uncharged, shot and killed her.

That day of Tamir’s death, I heard the echo of June Jordan in my head saying that “self-love is the most revolutionary act.” My baby boy is the best part of myself. I would spend the day with him, loving him. I would take him to the park and his favorite places. That would be my protest.

We took baby boy’s buckets and shovels with us, and like magnets, a small group of boys flocked to us in the sandbox. They looked so young, with their knocking knees and beautiful afros; I thought they were seven years old. “Are you in second grade?” I asked them. “No,” they told me, “we are in seventh.”

I did the math in my head and realized they were twelve. I remembered twelve was the age Tamir Rice was when he was shot. “Twelve,” I repeated. “Twelve.” They did not know why I started to cry. But they looked so young. They looked like babies. I was seeing their blooded brains and stomachs, bleeding out onto the playground. Twelve, with a gun, shot down.

All that day I had moments of sudden tears, not crying, just water slipping out from my eyes.

In April, 2014, Cliven Bundy and a group of middle aged white men drew guns and yelled threats at federal agents and police officers. ‘I’ve got a clear shot at four,” one of Cliven Bundy’s men is reported as threatening.

Stated Assistant Sheriff Lombard: “They pointed weapons.” And: “we were outgunned and outmanned.” But Bundy and his men, unlike the unarmed black children, were not shot dead, or even arrested.

It is, you see, about unequal application of force and justice depending upon race. It is about police brutality and racial profiling.

Darren Wilson, the white cop who killed Mike Brown called him a “hulk,” a “demon.” A witness called him a nigger. This is how they see us. Not as human. It has been documented by psychological studies that black children are seen as more criminal and not as young as white children are perceived, and the police act with increased violence accordingly when facing black children.

When I was a young girl of color growing up in Los Angeles, California, I wanted to become a writer to help end the virulent racism and sexism I had experienced, beginning when a white classmate called me “nigger” and pushed me off the swings in second grade. But now, as a black mother of a black boy, the systematic, often state sanctioned acts of violence by white men upon black bodies have become realer to me than they have ever been. Trayvon Martin, Aiyana Jones, Jordan Davis, Renisha McBride, John Crawford, Akai Gurley, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice. The list is endless. I realized that the only way I would be able to keep my son safe would be to use my writing to help make the world a safer place for black boys walking.

They call you a “political writer” then, as if that were a bad word. But everything is political. "Political” is only given a negative connotation when it is thrown at people of color for writing about our experience of living.

They call you a “political writer” then, as if that were a bad word. But everything is political. "Political” is only given a negative connotation when it is thrown at people of color for writing about our experience of living.

“How many of us have been told not to write about race? That, just by writing about your experience in the world as a black person your book is ‘too political' and will not sell?” I asked my peers at the Junot Diaz’s Voices of Our Nations Arts Fellowship a year ago and nearly all of my brothers and sisters of color raised their hands.

I know I will be told this again and again—as does nearly every writer of color. It is said in workshop as critique, by those in the industry as dismissal. But that doesn’t matter because there are more important things. There are some things that need to be said. There are some moments in history when, if you are a writer and been gifted with this uncanny ability to observe and make meaning in harmonious forms, you have a responsibility to look. To bear witness. As Junot Diaz said at VONA: “those of us who have been systematically erased or marginalized throughout history have a right, a responsibility, to speak for those of us who now cannot.”

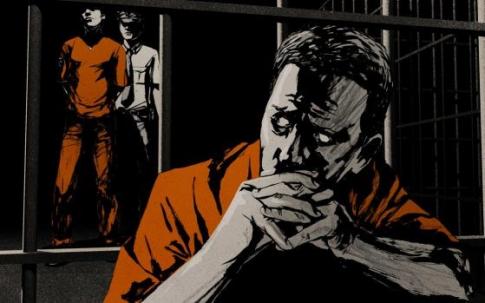

Illustrations by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review, most recently in issue 299.4, Fall 2014.