“Why become a storyteller?”

I’m tempted toward the snappy reply: “Because I so narrowly made it through, it’s my duty to blaze trail for the others.” For many years that duty angle, that in-spite-of defense, sustained my craft safe and separate, until I took my debut novel on the road last summer. I’d envisioned a safari, my inner Theodore Roosevelt tugging the moustache, hard eye gnawing the monocle, my novel -trophy a withered stuffed animal gone blooded buffalo slung upon the bow of the Spycar. “Bully!”

-trophy a withered stuffed animal gone blooded buffalo slung upon the bow of the Spycar. “Bully!”

Yet many times after readings I sat halted by a newer humility, the identity-part I called clumsy slightly better displaced.

In writing, I’ve come to value small progress. To write that thriller was to first investigate what said, “boo,” till I said, “boo” back—then transform that toad into lilies, or a comet--or let it go hop; boo who?

The craft helps me see—within, without—the two in harmony. Composing or revising, I groove in the mind-camera’s three dimensions – but with sound, smell, taste – eve indigestion—as real as the physical, practical reality to which I must return for provisions. I love the community of other writers, the connection on the page or on the screen or across the worktable. And the reader: when lights go on in the eye of the beholder—. Nothing beats that! Yet as author, fact is, I’m always steps behind the awareness, reaching – thinking, perhaps, I’ll include a detail that grabbed me years ago--a detail my innards know has made the scene real--a chime that also tells me that this inclusion, in some mysterious and invisible way, has righted a part of my life: written in, written out.

A muggy summer’s evening in 1992. A clapboard cottage in rural Tidewater, Virginia, where I worked, then, building marinas. A break from nightly writing.

Back of the peeling old mower shed, I pause where the land breaks off sharply to a deep, treed ravine that separates my sight-line from a nearby Baptist Gospel camp. Sitting on that mossy edge, smoking like many nights, the sermon drifts from beyond the eye-level tree tops in chunks the preacher’s words obscured by leaves—except for the muffled yet steady flow, with passionate bursts, dips, and runs of whomever is saving souls that night.

Soon the close, humid air goes cool. Dusk turns the tree-crowns to a sea. Then, forty feet above me the sky splits, spilling thunder, lightning bolts, a bath-warm cascade. And, as quickly: silence—dripping—a mist rising in silky wisps. Upon it, a musky, nourishing smell that fills my lungs with strength.

The sermon resumes.

Sense of the American south.

Walking toward the house for a towel, I halt. A fat droplet hangs at the lower tip of the mower shed’s flaking white rake board. Looking close, I see its baggy lens has entrapped an image of my tiny white cottage, my pickup truck, my yard, the barbecue grill—bulging image, everything upside down the globule obeying every law of physics, breaking every rule of subjectivity, yet not bursting.

I was thirty-two that summer that moment I decided to quit my job, get a degree in English, and commit to a life of writing the sublime and unhallowed.

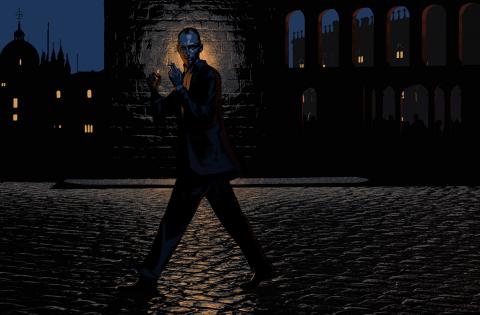

Twelve years later, while preparing to face Nick Giaccone, the retired detective who will take her down, my novel’s arch-villain, The Illuminator sees her world inverted, distorted within a water drop that dangles from an icicle’s tip. We see the droplet falling. She closes her eyes, leans forward, and catches it on her tongue.

Tom Lukas‘s home is in Seattle and Bogotá. He received a Ludwig Vogelstein grant to finish his first novel, Contrapasso, or, a Season of Consequence, for which he seeks a publisher. Tom is featured in issue 294.6, November-December 2009.

Illustrations by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review issues 298.4, 299.1, 299.3, 299.4, and most recently in issue 301.1, Winter 2016.