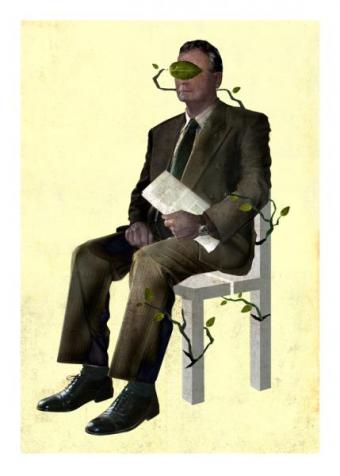

When people ask me what I write about, I sometimes tell them that I am drawn to visionaries with blind spots, especially would-be scientists or artists, or especially figures in history whose ideas were progressive for their time, but are now regarded as absurd, or as pseudoscience. One of my first published stories was about Eliza Farnham, the first matron of the women’s wing at Sing Sing prison, who attempted to reform prisoners using phrenology. Around that same time, I wrote a story about the Hungarian doctor known for founding the practice of iridology, diagnosing health ailments by studying the patterns in his patients’ irises. I am particularly interested in these idiosyncratic ideas—theories we might laugh at now, or criticize for their harmful biases—because of the way these characters seek to understand intangible, invisible things by reading the tangible, visible surfaces of the body. There is something alluring about such systematic coincidence, even though it is so often false.

“The Skin of a Rabbit,” my story that is included in the fall issue of North American Review, features one such “visionary with a blind spot.” The story, which appears in altered form in The Good Echo, my debut novel, due out in November, was inspired by the life and work of Weston Price, a dentist and nutritionist with unconventional theories about dental health and nutrition, and how they shaped our bodies and minds. Many of Price’s ideas seem like common sense to us now—namely that whole food, local diets are good for us—but in the 1930s, when Price was writing and researching, he had fallen out of favor with the National Dental Association, a professional organization that he had founded, because he was so committed to focal infection theory, the theory Clifford Bell, my fictionalized version of Weston Price, is busily developing in “The Skin of a Rabbit.”

“The Skin of a Rabbit,” my story that is included in the fall issue of North American Review, features one such “visionary with a blind spot.” The story, which appears in altered form in The Good Echo, my debut novel, due out in November, was inspired by the life and work of Weston Price, a dentist and nutritionist with unconventional theories about dental health and nutrition, and how they shaped our bodies and minds. Many of Price’s ideas seem like common sense to us now—namely that whole food, local diets are good for us—but in the 1930s, when Price was writing and researching, he had fallen out of favor with the National Dental Association, a professional organization that he had founded, because he was so committed to focal infection theory, the theory Clifford Bell, my fictionalized version of Weston Price, is busily developing in “The Skin of a Rabbit.”

Like my characters, Clifford and Frances Bell, Weston Price and his wife eventually followed Price’s ideas to the proverbial “ends of the earth,” spending much of the 1930s traveling to remote villages in Alaska and Switzerland and Sudan, seeking people who still ate traditional diets of unprocessed foods. Together, the couple collected samples of milk, meat, and blood, grains and soils. They photographed children and adults grinning for the camera to reveal their fine or rotten teeth, the shapes of their faces, the particular sets of their jaws. But Price’s ideas, like many ideas, were bound by his time, and by the limits of cultural paradigms. In the story of Clifford Bell and his keenly observing wife, Frances, I consider what it might have been like to visit such places, to try to understand the ways of life of the people there, and to try—and often fail—to separate nature from nurture, fate from historical and cultural context.

Phrenology, iridology, and eugenics. Religion, art, and science. Our systems of understanding the world often prove flawed, or at least limited, but in our acts of dedicated reading and misreading, I see that the passion of the monomaniac is not unlike the passion of the writer, toiling for years on her novel, the scientist seeking a cure, or the artist refining her vision. And such passion is magnetic, even—or especially—when the passion’s light is blinding.