Oh, yes—like most poets and writers, I receive rejection letters:

- Some are merely form notes, pre-printed.

- Some are form notes asking the poet/writer to send work again.

- A few are form notes with personal, hand-written notes added, complimenting the work and asking to see more of it. Or personalized emails.

- A very few are personal letters or emails that mention specifics about work and ask to see more.

In this era of Submittable and other submission managers where work is sent online and then accepted or rejected the same way, there are often no notes at all. What does this all mean, you may ask?

Maybe it means nothing except that different editors have different styles of replying. Even the form note, pre-printed by snail mail or inserted into email, may mean nothing except differing methods of dealing with a large number of submissions. And, yes, this is the place that I must (full disclosure) admit I am a journal editor as well as well as a poet and a writer. . .

So let's go back to the title of this essay. Most rejection isn't personal.

- What you submit may not be the kind of work a magazine publishes. Did you read issues to see if you think it is well-matched to yours?

- You are not being rejected because of your cover letter even if it's very brief or long and cites the 100 journals in which you have published work. Or because the editor doesn't like your ornate font.

- You are generally not being rejected because you have blond or black hair, because you weigh too much or too little. You are not being rejected because you have or don't have an MFA in creative writing or because you don't have a university teaching job.

- You may be rejected because you sent the editor dream poems and he/she has just accepted a lot of dream poems. Apply this also to poems about children, grandchildren, adulterous spouses, dying parents, friends, or spouses.

- You may be rejected because the editor feels you have submitted work that is anti-feminist, racist, or politically incorrect for her/his publication. Even this is not personal. Some editors welcome controversial or confrontational work and feel political correctness has gone too far.

On the other hand, you may find work accepted because you are young, foreign-born, non-Caucasian. Or your submission may be accepted because your writing comes from a state seldom represented in a journal, or because your occupation (other than writer/poet) gives interesting insight into what you have submitted. Embrace that. (When my 6'4" son was in high school, he decided that if anyone gave him a job because he was tall, he'd take it. In other words, use anything that seems to be to your advantage.)

Still, read this next part carefully: A few rejections are personal.

- You may have withdrawn work previously accepted by some journal to publish it elsewhere.

- You may have annoyed the editor by submitting more poems than the guidelines stipulate or submitting work outside of the submission period.

- You may know the editor but not be on good terms with him/her. (This happens. I seem to have been permanently blacklisted by an editor whose travel poem about twirling in Vietnam in a blue skirt I rejected. Before the blue-skirt incident, her magazine had published my work regularly. And I did write a long personal note and ask her to submit more poems to me, which she didn't do.)

- Or you may, like me, not be young enough for an editor to expect you'll become suddenly, wildly famous. (It's okay. Calm down, we should all love young talent, fresh promise, even when it gets them accepted and you rejected.) Very good minor poets are important, too.

So here is my advice for you:

- Keep sending out work. You can't be in any creative field long-term if you cannot deal with rejection.

- Send written work/poems you feel are "finished" to the best of your ability.

- Only submit your best work, whether the submission is to the New Yorker or to a less well-known publication.

- Lastly, it's all right to fail. Rejections should make you stronger. They should make you want to redouble your efforts to write well, to receive fewer rejections, and to feel you are succeeding.

Susan Terris’s most recent book is Ghost of Yesterday: New & Selected Poems (Marsh Hawk Press). She is the author of 6 books of poetry, 15 chapbooks, and 3 artist's books. Journal publications include The Southern Review, Denver Quarterly, The Journal, North American Review, and Ploughshares. A poem of hers from Field appeared in Pushcart Prize XXXI. Susan's piece, "Before Cortez," appears in issue 295.2 of NAR. She's editor of Spillway Magazine. Her book Memos will be published by Omnidawn in 2015.

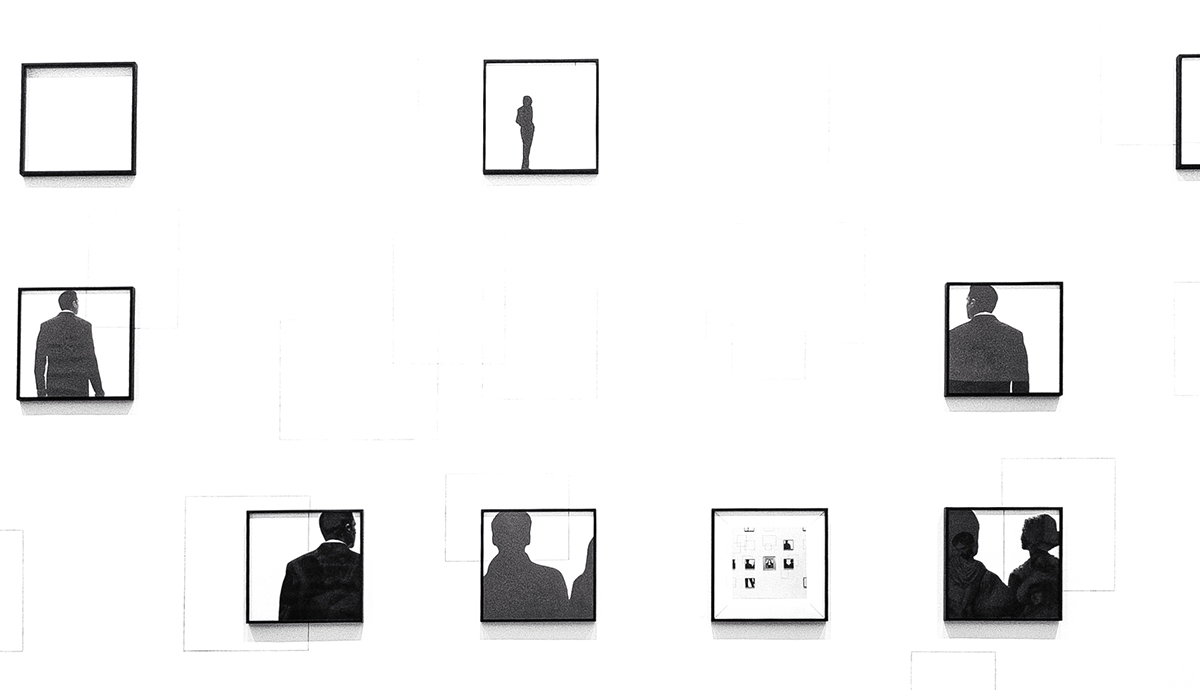

Photograph by Quadell.