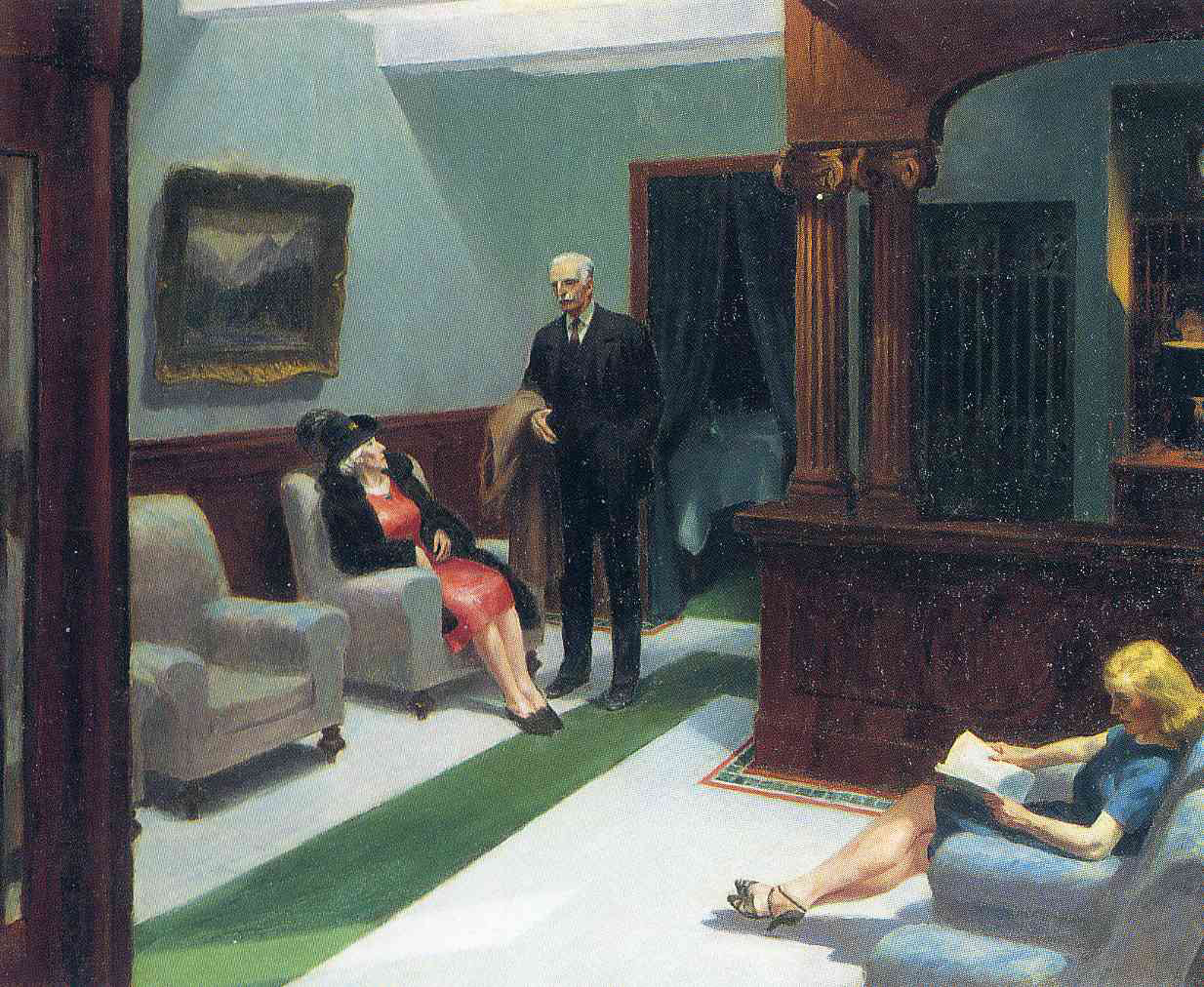

The Lobby

You are a fast first glance in my direction when you walk in the door and you are tired and your day is long and you are looking for a place to give yourself over to the heaviness of sleep. I am the rustle of movement to your right that tells you I am here, that someone is here, even before you see me. And when you see me, I am the face that meets your own. And it is framed by the dark wall, and I am wearing the green dress, and in this time and in this place, I am framed. And you are the greeting that echoes back my own, and I am the quick quip while I run your credit card, and you are the face on your driver’s license that I check each and every time, a set of matching eyes squinting back into mine. And then, my shift is over and the rest of your day falls into something unknown to me like colored sand into a glass beaker. I can’t see through it anymore.

Now it is the next day, and I am calling you a cab. And then you are outside, and in the peculiar cloistered world of a small hotel lobby nestled in a Chicago side street, you don’t exist anymore. And then I glance up while I’m flipping through the deck of daily check-in cards and catch the profile of your silver head of curls on the bench out past the window, and realize you are still here: always were. And just like that you exist again. Just like that, you always have.

And when I stick my head out the door to see why your cab hasn’t arrived, I exist to you again, I am once again real in your world, and this is temporary, and when you lift your chin to meet my gaze we exist to each other, and this is temporary, too. This is all temporary. And you were here to see your infant grandbaby for the first time and you think that is the miracle, but actually, I think all this is the miracle. And you think that I keep popping out to see if your cab is coming. And I am, and there are three separate cabs coming now from three separate cab companies to ensure that at least one is coming, but when it does, there’s something else that gets away. You are gone, and I think the way you are gone, when you are gone, mirrors the way any of us are gone when we are gone.

And nobody tells you how many times we go, over and over and over, before we go. It is another morning, another day, another guest, another me in another dress. Her name is Sheila. She is set at the table by the window, bathed in cool filtered light from austere Chicago spring; she is drinking hot coffee and handwriting loopy scripted postcards. We speak, for some reason, about Bambi and the Wizard of Oz, how many children’s stories are unspeakably sad as a grown-up. Her grandson is graduating high school, and this reminds her of her other grandson who never will. She tells me where he went. St. Louis Children’s Hospital. She needs for me to know where he went. They are going, now, and her husband is slipping me a twenty and she is saying goodbye to me with this ancient sadness that cannot be placed, and I can’t think of what there is to give her to fix it so I grab a handful of hotel-branded postcards from the drawer and hand her a short stack because one doesn’t seem like enough. And I hope that it is enough, and I know that it wasn’t. We mattered to each other by dint of what we lacked: there was something we needed out of each other that we were fundamentally unable to give.

And I wonder what we are to each other now. A paisley shirt on an ambiguous morning. Steam rising from a cup of coffee. A postcard in the mail and a stack unsent. And the truth is that Sheila has made me think of my own grandmother, Gloria, who is out there but only in the way of a distant planet or perhaps an alien on its surface, miles and years out of reach for reasons that, like most such things, everybody can explain and nobody can explain. This woman, my mother’s mother: an invisible shadow cleaving to the shape of my life. She is nothing in my memory but a few snapshots ending at age eleven and a pile of letters returned to sender which grows by one by the year.

Here in the lobby, I exist in a series of stills.

I write to Gloria again that summer on a hotel-branded postcard. I plan to hand it on my last shift to Walter, the grouchy mailman who circuits our lobby near-daily to hurl with high velocity a pile of envelopes at the front desk, and without a word, limp in broad strides to the coffee bar, cutting a patient line of guests to help himself to generous volumes of coffee, cream and sugar. My coworker, Jason, groans and bends over to thump his head on the desk violently at the sound of Walter’s roll-cart breaching the door. He knows that in ten minutes, one of us will be furiously sweeping sugar granules off the coffee bar where he has spread them like a crop duster. When I see Walter for the last time, I wave goodbye and the postcard stays in my bag. It lurks still in my bedside drawer. I cannot tell you why. We cannot answer our own riddles.

We are passersby, and that is so little, and we are passersby, and that is so much. I realize this watching Walter, warring with Jason over relentless sugar crumbs; watching stereotypically, mythically Midwestern families gather in the lobby all hands-on-shoulders and raucous laughter that fades, each and every time, into nighttime’s silence. I realize this learning the rhythms of the lonely ones who loop by and by again like the midnight train on its trundling circuit; I realize this clustering at the big windows with the whole lot of them to watch the wheedling fire-trucks or the angry summer stormclouds roll by as if we were all living here, and living here forever; as if the windows will always be the windows and the view always the view; as if this is our home and the thing we will remember it as. We are all living upstairs forever, in these moments, even though none of us ever were. I am simultaneously a part and not a part of anything that happens here, just as I am, really, a part and not a part of anything that happens anywhere.

Nobody knows my last name, my coffee shop order, the way I wind my way slowly home. They only get my blinking eyes, my fast rise at the sound of the front door, rising as if I have always stood. They must think that I have always stood. And maybe I have. This place was built in 1923. Al Capone tunnels wind yards below our feet; allegations of hauntings hang in the air. We play unceasing loops of classical music and big-band oldies. A gentleman – we refer to them all as gentlemen, even when they’re not – arrives in a suit and a conference lanyard with a hardcased luggage and stops in his step to take it all in and tells me in hushed tones, “wow – it’s like stepping back in time.” The next day I do my hair in pin curls and clip my bangs with pearled barrettes, because if I am working in a room which steps back in time, I too, must step back in time. This room is my world now. These hours are my clock. This place is the frame that holds me and for a while, I let myself be held.

And I think in this frame I might be real in a way I am not even real outside of it. I am so little to you, and so little you to I: the momentary glance, the fleeting smile, the dance of etiquette, the brief championship of language over silence. They say my job is simple and it is. I am here, only a face, in the words of T.S. Eliot, to meet the face that meets you. But I am, in this face that meets you, here; in this linen dress, in this frame, I am here. To be here feels like, for as long as it lasts, the only thing in the world that is real.

Here in the lobby, I exist in a series of stills. You all exist in a series of stills. We use the phrase “snapshot in time” for a moment in time because in any given moment, distilled down to the hairbreadth of a hairbreadth of a second, down to the single point a line could, hypothetically, furl back into, we are exactly that: a snapshot. A person in still image. A life in stills. I used to have a kineograph book as child. You flipped the outer edge of the pages with your finger to run from top to bottom quickly and what unfurled before you was a short, analog form of video: the images changed almost fast enough to be happening on the television. And ever since then I wondered if the smoothness we feel is an illusion.

Late night after my last shift ends, I lie awake instead of sleeping – awake for things upon things upon things, that day the sole fell off my shoe, the hurricane of luggages when an entire national soccer team descended on us at once, stolen mini-bar vodka on cancelled cards and stolen sheets in overstuffed backpacks on their way out the door, doodled hearts on honeymooners’ keycards, champagne in a basket, false alarm fire alarms, locked-out late-nighters and locked-in oversleepers, early mornings and late nights, this lobby a million ways, and I, awake for it all. For the maintenance man who talked me down, or up, rather, off the floor, for the second-floor housekeeper who taught me how to tuck in pillowcase edges and ended every front desk call with thank you baby and eventually, love you baby, for months of crippling laughter, practical jokes, and the countless small chronicles of unsung heroism that make a hotel functional and a life livable. But there’s more. The sort of thing that’ll keep you up for life if you look up at it in full blast. Summer storms scrawling on the great front windows. The quiet rustle of a turning page that tells me you are here. The small concavity at the bottom of an emptied coffee cup, joining a pile of emptied coffee cups in the kitchen sink at the end of a day’s check-outs. Faces that have already slipped through memory, as mine in yours, hands that held my own and then shrank into an untouchable past, the ordinary and casual loss we must swallow like a daily pill, in the lobby or in the street or at the last of anything.

They say that grief is a process of letting go of old objects and substituting them, ever so gradually, with new ones. We are changing out, changed out, we are snakes shedding their skin. All of these miniature losses, a thousand scales unleashed from the body. Change is not really change at all. Every new substitution retains a trace of the old. The trace is ancient, interminable. The trace is embedded in our soul, and one might say, in our DNA. Loss is regenerative, continuous. Grief never ends and ends every day. Love is always old and new. Plato suggested we can never know what we don’t already, in our soul; never love what we don’t already love. What he might have added is that we can never lose what we have not already lost.

Grief never ends and ends every day. Love is always old and new.

You are passing, you are passing out of sight fast as a twenty-four hour Standard Queen turnover, you are passing like a taxi in a Chicago side street, like a line of women in my ancestry walking into the unknown. And I know, as you grasp my hand over the ballast of the desk and won’t let go for a little too long, that when you hold me, you are holding onto someone whose name I will never know. We are more than ourselves. We love more than each other. The great wound and salvation of love is that we will never entirely understand who we are to one other, our shadows falling onto other shadows in our lover’s eye, the shape of our soul cleaving to imprints stamped by the shapes of all they have ever known. We will never entirely know who it is we love or who it is we are when we are loved.

It’s not just that we once built gingerbread houses together, me and you, Gloria – you are the riddle under the riddle, the hot breath in the mouth of the Sphinx, the molten core at the heart of the earth binding me through my mother’s and her sister’s depths and waters. I am your child’s youngest child, I am your youngest grand-, I am the final fruit of a generation that before it was mine, was yours. I am your substitution. You are the original wound, though yourself only repeating – ninety years of flesh under the scab, the poisoned, colorful seed at the heart of my growth. You are my destiny retrospectively seen. Your lavish taste for words, my literary origin; your incurables, condemned to repeat. You are the butterfly that flapped its wings in my Brazil.

And you are also nothing to me now but a few snapshots in a short history and an unsent postcard in a drawer. And my striking, wild grandmother rustling in a navy sequined dress – do I remember it in the real, or only from that old photograph, a skeleton whose movement, whose shake and rustle was only fleshed in by implication, the way the sight of a vase fills in its invisible far side? And in all conceivable likelihood, the next time I see her face again, pale as the moon and as still, she will be gone. And we all say see you next time here at the swinging lobby door, but they don’t know that moving across the country in a month’s time I will be gone, and none of us know when we will be gone. And what we get of each other, what little rubs off on the skin: I hope to God that it’s enough. Because what I get of you will always leave me, and it will also never leave.

Recommended

I Have Only Dreamed You Dead, For Now.

Encounter

Schizophrenic Sedona