Last night was the kind of night in San Diego that starts to make interesting promises about spring. At 10 p.m., the air smelled like flowers, and the curving sidewalk leading to my new apartment was littered with a scruffy blend of dropped white blossoms and palm-sized sweet gum leaves.

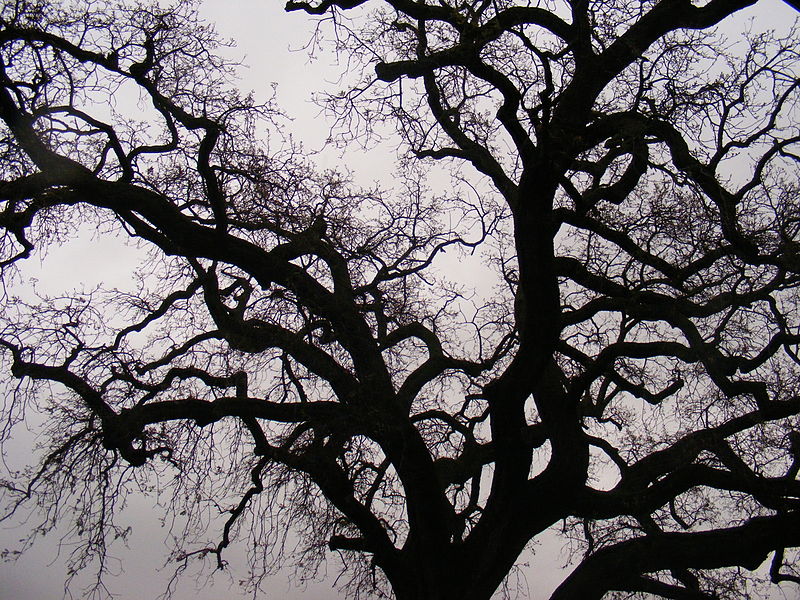

In fact, I have been watching this one dark-skinned tree in particular for several weeks, since I first moved in. Feeling a little heartsick these days, I walk beneath this tree every morning en route to my parked car and offer a little unofficial prayer that its reckless blooming will shower something brave and amazing down on me.

Last night, though the air smelled like flowers, bad dreams ripped me from sleep three times so that I woke up in the dark, soaked in sweat, and texted my sister in Washington, D.C. When will I start feeling better?

Her reply came in the morning, along with the sun: Honey, it’s hard to say.

I had made myself three promises to start the new year: Be brave, be honest, and listen carefully. Last June, a great poet read through my manuscript excerpt and told me, starkly, that I risked nothing in the poems, making them pretty much unlikeable and unreadable.

“You’re hiding your face,” she said. “Stop doing that and start over.”

James Baldwin writes beautifully about fear and safety. “That one resist at whatever cost the fearful pressures placed on one to lie about one’s own experience.” “Art is here to prove, and to help one bear, the fact that all safety is an illusion.”

“It is a total risk of everything, of you and who you think you are, who you think you’d like to be, where you think you’d like to go—everything, and this forever, forever…The price of that is high. The price for that is to understand oneself.”

And this: “Whatever one’s journey is, one’s got to accept the fact that disaster is one of the conditions under which you will make it.”

We all learn tricks to survive in some way the homes in which we were raised, I suppose. For myself I learned perfect control and absolute confidence. I slept with my hands on the handles of these knives; they seemed to me my best chance at safety.

Here is what Jane Cooper writes about safety: “I had to get through the perfectionism of those early poems, to learn that no choice is absolute and no structure can save us.” She quotes Anaïs Nin: “In order to create without destroying, I nearly destroyed myself.”

After the great poet’s advice, I realized it would not be possible to play it safe in my personal life and simultaneously take risks in my poems. There would have to be risk in both places, or safety in both places, and Baldwin had already advised me that actually, there is no safety in any place.

“Universal concern is not enough,” Cooper writes.

Once I thought I was about to die. Anchored poorly in a Caribbean winter storm, we woke up before dawn sort of nightmarishly near a jagged shoreline. Huge jade swells shambled the 72-foot, unmoored sailboat under our care roughly toward the sea cliff. Rain hammered my whole body and the whole world into dumb noise.

You don’t have a choice but to be brave in a situation like that. Possibly, it doesn't even count as bravery.

You just miserably do the things that need to be done (namely, steer the out-of-control, bucking-bronco vessel into blind storm, in your undies, watching terrified as a man you love dangles himself like a piñata over the swell-buried prow, looking for shallow reefs) until he finally says things like, It’s OK, the storm is clearing, I’m proud of you, dry off, go back to bed, I’ll be down in a minute.

Writing poetry and living ordinary life are slightly different in that these are on-your-honor systems when it comes to being brave and honest. There is choice. Consider the smaller acts of cowardice, like crappy tips and comb-overs. Disguising your upbringing to suit a social setting. Pretending indifference when actually you are not indifferent.

Once I tried to write a poem about how hard it is to write a poem about sexual violence.

My poetry mentor slapped his palm on the poem and said, “I’m showing up for this poem, and this poem is not showing up for me. I am ready to hear what the speaker really wants to say, but clearly the speaker is not ready to say it.”

Rilke writes: “I live my life in circles that grow; / upon it all their lines seem to press. / Though I may not manage the ultimate circle, / I will give it a try nonetheless.”

Driving through a Minnesota snow in late November, I tried to answer a friend’s question about love. Namely, yes or no? She said, You know the answer in your body. She said, When I count to three just open your mouth and let the truth come out. She counted to three. Trusting her, and feeling hopeful, I opened my mouth. Nothing came out. No yes. No no.

I don’t know who I am, is what I finally said.

But you have to try for something anyway. Anne Carson writes, “It has to do something to be a weapon.”

Truth is not the wickedest weapon, but it can unfortunately be both a party trick and a bad bargain. As in, I’ll tell you the truth if you give it a warm welcome. Truth does not always get the welcome it wants. A true poem can still be a bad one.

My friend lets me cry on the phone for 45 minutes last week. I am sitting in a parked car watching my beautiful dark-skinned tree show off its ridiculous snowy blossoms, annoyed that it is not safekeeping my heart that way I have asked it to. “I like this new you,” he says. “It’s like you’re human.”

Being human, as you know, is not a party trick. When people say “human,” they mean “imperfect.” Or they mean, “You remind me of me.”

“A tongue has one customer, the ear,” Rumi writes. And: “This is how it always is / when I finish a poem. / A great silence overcomes me, and I wonder why I ever thought / to use language.”

“All I can eat is peanut butter,” I tell my sister in Ventura. Then I listen carefully.

“You are being stupid and dramatic,” she says.

Because I love making art, and I love being alive, I am trying to be brave, to be honest, and to listen carefully. And so far this year, interestingly, it’s been the perfect fail. All pain, no gain.

Jane Cooper writes: “I seemed to have made a mess of my most intimate friendships, and poetry—that gift for seeing far and seeing through—now looked less like a source for renewal…than the house-wrecker.”

The dark-skinned tree is absolutely losing its blossoms. “All stories stop,” Christian Wiman writes. Shiny green leaves unpeel from the branch. Back to the business of growth, because all stories necessarily continue, too.

When I was little, we had pet rabbits. They grew wilder and meaner over time, so that feeding them became a terrifying chore that involved hurling armloads of carrots and celery into the big wire hutch beneath our backyard orange tree. Petting them eventually became out of the question. We were lucky to just watch them vault around the hutch like vicious, souped-up kangaroos, or rampage my mother’s tomato and strawberry gardens.

The trade-off, I guess. My poems rarely let me pet them these days. They’ve lost their good manners. I can’t get close enough. Braveness is a moving target, with teeth and some fury.

A poetry mentor once wrote to me: “Stop saying things about your poems that you wish you were brave enough to say about yourself.”

Petting a bunny might be a waste of time, but so actually are rabbit bites. I like to overemphasize the risk of injury to my yoga students when teaching potentially dangerous poses. (And isn’t anything potentially dangerous?)

“You will get hurt,” I promise my students. “So listen carefully to your body when it talks to you.”

And fuck you, bunny poems.

I am on a date. We bend over the same taco plate. He says, There’s something caught in your hair. He untangles what turns out to be a little stemmed, dried-up blossom and then tucks it into his buttonhole, no biggie.

“Dylan,” he tells the bartender.

“Flowers in her hair,” the guy agrees, keeping an eye on Sochi 2014.

The lyric, because life is hilarious, comes from Dylan’s “Shelter from the Storm.”

Carson: “This would be hard / for you if you were weak / but you’re not weak.”

And: “people need /acts of attention from one another, does it really matter which acts?”

Poems, like anything else you risk to love, will take you out like a shark attack. Like a bunny bite. And then life does this thing where it imperfectly and astonishingly moves on.

Emily Vizzo is a San Diego writer and educator who recently completed her MFA in writing at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. A National Writing Project fellow with the San Diego Area Writing Project, Emily currently teaches yoga at the University of San Diego. She completed her first poetry manuscript at the Vermont Studio Center in August, and her North American Review essay, “A Personal History of Dirt,” was recognized as a notable essay for Best American Essays 2013. “A Personal History of Dirt” is featured in issue 297.3. Emily serves as assistant managing editor at Drunken Boat and volunteers with Poetry International.

Photo Credit: J. Smith