One of the most salient revelations in The Great Gatsby, the origins of Jay Gatsby, née James Gatz, is embedded in Chapter 6 of the novel. We learn of Gatsby’s upbringing: a farm boy from North Dakota raised in poverty. He goes to college but drops out because he’s ashamed of having to support himself as a janitor.

Edward Fitzgerald, Fitzgerald’s father, whose wicker furniture business failed and who then lost a subsequent job with Proctor and Gamble, was reduced to living off his wife’s inheritance. In Fitzgerald’s celebrated novel, the author imbues Gatsby with fierce ambition that leads to a meteoric rise and then an infamous fall. No doubt the real-life failure of Edward Fitzgerald imprinted itself on his young son and became what one might call “the backest backstory” for the author.

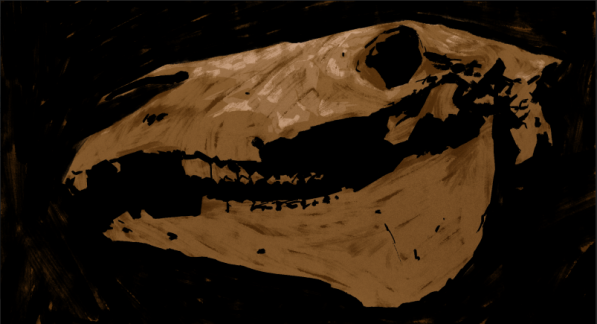

My father, also a furniture merchant, went bankrupt like Fitzgerald’s father. Often I wonder if I’ll ever be finished with how much this business failure dominated our family’s life and figured into my relationship with my father. Or if I’ll stop writing about it, even when I think I’m not. My latest story, “The Horse Burier", in the bicentennial issue of North American Review, only made this more apparent to me. The premise concerns that of the son burying a horse and needing his father’s help. The story’s events, taking place in rural Colorado between characters of vastly different background from my own, could not be further from my experience. And yet the central conflict, about “buried” resentments never resolved, thrives on a silence between father and son, as did my own experience. The “backest back story” is realized in the story when—spoiler ahead—the son starts to “bury” the father alive. In my case, a metaphorical act made literal here.

My father, also a furniture merchant, went bankrupt like Fitzgerald’s father. Often I wonder if I’ll ever be finished with how much this business failure dominated our family’s life and figured into my relationship with my father. Or if I’ll stop writing about it, even when I think I’m not. My latest story, “The Horse Burier", in the bicentennial issue of North American Review, only made this more apparent to me. The premise concerns that of the son burying a horse and needing his father’s help. The story’s events, taking place in rural Colorado between characters of vastly different background from my own, could not be further from my experience. And yet the central conflict, about “buried” resentments never resolved, thrives on a silence between father and son, as did my own experience. The “backest back story” is realized in the story when—spoiler ahead—the son starts to “bury” the father alive. In my case, a metaphorical act made literal here.

My father is long dead, I’m in my sixties with grown children, and yet if I peer deeply enough into my NAR story I see it’s engendered by a personal backstory that though it may have grown distant over the years has nevertheless lost none of its force; it’s just gone deeper underground, interred by the downward pressure of time and personal history.

What writer wants to lose his or her furthest backstory? You may want to resolve it in life, but not in art. Sometimes you will think this backest backstory has disappeared all together. You may have to track its fainter movements, detect its subtler traces. You may have to gentle it out of hiding. But it hasn’t vanished. Its consequences, shape, signature, familiarity, and boldness are still there, inextinguishable. Had Fitzgerald lived past 44 he would still be writing about how the rich are different from you and me, trying to redeem his father’s losses. Meanwhile, I’ll go on writing through the disguise of fiction about seeing my father lock his store’s door for the last time and what that meant about heartbreak and failure to him, and to me.

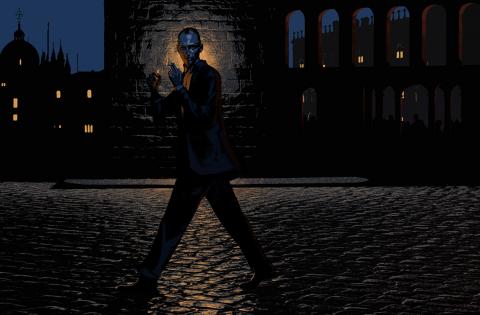

Illustrations by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review, the most recent was in our bicentennial issue 300.3, Summer 2015 which is shown above.