Around 5:30 PM on Monday, December 8th, 2014, a couple down the road from me, Patricia and Stuart Little, both in their 70s, returned home from a shopping trip. When Mr. Little fell while getting out of the car, Mrs. Little was physically unable to help him up. At that time, like most houses along the rural Creek Road, the Little's were in the dark, owing to a storm-wrought power outage which rendered the Little's home phone useless. Presently there's no steady cell service in this remote part of Vermont, so Mrs. Little struck out across the snowy field to fetch help from the neighbors.

In Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, which was a one of the last precincts in America to be electrified, this delayed or lacking linkage to grids and networks means that people who live here are, by necessity, deeply and directly tethered to each other.

These kinds of connections tend to withstand power outages and missing bars on smart phones. Like mycorrhizal fungi running under the soil, exchanging information and resources between trees, there is a secret service contract between residents of the Kingdom, an unwritten "thou shalt look after your neighbor" system here. My next door neighbors exemplify this, once calling to inquire if I had broken up with my boyfriend, noting, "We haven't seen his car in your driveway lately." We have not, I replied, saying he was simply busier these days than before.

Well, guess what, they'd clued in sooner than I had. Yup, I soon learned, he and I were done.

Alternately, they often checked in to see if I was, "Ok" saying, "There's a lot of snow on your car, and it hasn't left the driveway recently. We wanted to be sure you were alive in there."

My poem "Migration of Baling Twine" was inspired by these kinds of mundane connections that bind us together. My poem (full disclosure) is also a love child born from the coupling of Nancy Willard's poem "The Migration of Bicycles" and author Helen Scott Nearing's passage about "love" as a connective substance. I was inspired by Nancy Willard's playful poem included in her collection, In The Salt Marsh (Knopf, 2006) where she observes the behavior of bicycles with the same intensity as a wildlife biologist chronicling a pride of lions, reporting how they operate singly "balanced on one foot like a clam" and in clusters, "...a whole pack / will stand for hours in the rain." As anyone whose ever strolled through a backcountry barn knows, baling twine is as ubiquitous as bicycles in the city--so commonplace as to be invisible, and yet... Helen Scott Nearing, author and co-author of a kind of back-to-the-land Bible, The Good Life, later wrote (I have to approximate, as I can't find the passage right now) that she believes this world is held together by ordinary strands of love crisscrossing the globe. Long before the internet she said that she thought our loving thoughts crossed the distances like a spider's silk and made a net that kept the planet in tact (or something like that).

Another piece that secretly informs "The Migration of Baling Twine" is William Stafford's poem "A Ritual to Read to Each Other" with its threat of broken links and severed ties: "For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,/a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break" and its consequent, "lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark." Any connection, Stafford suggests, be it a fungal strand, a transcontinental phone call, a loving bond, an artery to the heart, or a piece of twine tying the door open, is subject to rupture, a rupture that could equal disaster.

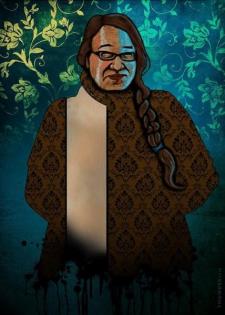

Mrs. Little never made it to the neighbor's house. The combined circumstances of grave illness and no power to call out meant that Mr. Little was unable to rescue the wife who'd set out on behalf of saving him. He was discovered inside his house in medical distress by a relative who visited two days later, whereupon, the relative alerted authorities of Mrs. Little's disappearance. She was found, halfway across the field, no longer alive.

Despite all our connectivity, both it and our humanity are fragile, fallible, friable as baling twine, anything but foolproof. The warning contained at the end of Stafford's poem haunts the Littles' story, haunts all our stories, "the signals we give--yes or no, or maybe--

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep."