Readers of the North American Review may remember from the Summer 2010 issue Silas Dent Zobal’s story “Wretchedness,” which begins with this virtuoso sentence:

Salvation goes like this: I’m bulleting snowballs single handed—the right’s occupied with a tumbler of gin—at two youngsters, whose forgotten names cause me to question the nature of memory, on a snow-covered lawn that ain’t mine when Carmen, my on-again off-again spouse, brings her father, Boyd E. Plumley Jr., and her sister’s second husband, Deputy Cooke, screeching to a halt on the two-lane in the Deputy’s cruiser, flashing emergency colors.

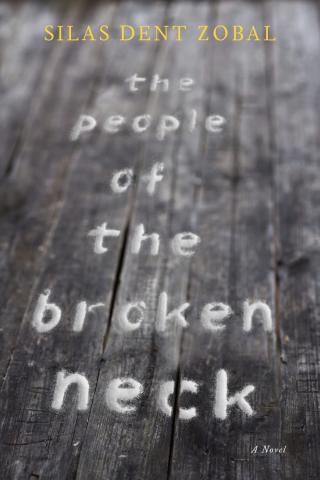

With such a compelling voice (and a stop-and-start syntax that comes “screeching to a halt” itself), how could you not want to go on this particular narrative ride? “Wretchedness” later appeared in the pages of Zobal’s collection of stories The Inconvenience of Wings (Fomite Press), named one of Kirkus Reviews’ Best Books of 2015. Earlier this year, Unbridled Books published his first novel, The People of the Broken Neck, which Publishers Weekly calls “A tour de force of a debut novel.” I call it in my review in the current North American Review online “an exquisitely rare novel, at once a page-turning thriller and a meticulously crafted work of literary art.” I had the pleasure recently of corresponding with Zobal about his new book. Unsurprisingly, he was deeply thoughtful and insightful in his answers to my questions.

J. D. Schraffenberger: First of all, Silas, congratulations on the publication of The People of the Broken Neck. It’s a truly remarkable novel, and I’m excited to talk about it with you.

Silas Dent Zobal: Thanks, Jeremy. I loved writing this novel.

JDS: You don’t have a military background, but you describe Dominick’s Army Ranger experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq with precision and authority. I’m assuming that his comfort and familiarity with guns is not something you share, nor is his suffering PTSD. I suspect that you must have done a lot of research to render these moments believable, but I’d like you to talk more about this process—not just reading about but also the narrative need to inhabit characters who are very much different from yourself.

SDZ: Yes, this book took a lot of research in different forms: reading soldiers’ memoirs helped, and studying up on articles about PTSD, and having long conversations with a friend who’d recently returned from Iraq. There’s more, and maybe it’s useful in a craft sense, but what really interests me about your question is the phrase “narrative need.”

Right now, I think there are two opposed and necessary narrative needs: the first is a drive to inhabit characters who are like us (i.e. to bulwark notions of self and so define otherness); and the second is a desire to inhabit characters who differ from us (i.e. to foray outside the self’s bulwark and so open the self to revision).

The first need is, I think, the purview of much literary realism, science fiction, fantasy, mystery, romance, etc.—in short, stories that aim (sometimes unconsciously?) toward affirmation. Other stories (sometimes consciously?) aspire to, even if they fail to reach, a re-envisioning.

They’re both important, I think, both necessary. But when I’m writing I’m usually more drawn to looking outside of my experience. Let me go one step further—but, as I’m not interested in moral hegemony, I’ll only assert the following for me and not for you. For me, it’s a moral imperative to move outside of myself to whatever degree I am able. When I don’t, I feel like an ass.

JDS: In some ways, this is a follow-up question. People are always interested in inspiration and influence. My question is not about specific influences, like reading Hemingway or living in Washington. Rather, I want to know about the transformation of experiences into fiction. How do you reshape or refashion your life so that it becomes the lives of completely made-up people?

SDZ: I start with experience (the bon mot “write what you know” holds water momentarily) but then, in short order, experience or the known leaves my writing feeling hollow and disengaged. A pale simulacrum of the real. That’s when I begin to sense that the known simply isn’t enough. We must, I think, give our work what we have, but then we have to give it more. And there’s nowhere else to go but to the unknown.

(Also, when I stick to what I know, I’m bored. And I think the reader will be, too.)

In an interview for the Paris Review, Hemingway said, “From things that have happened and from things as they exist and from all things that you know and all those you cannot know, you make something through your invention that is not a representation but a whole new thing truer than anything true and alive, and you make it alive, and if you make it well enough, you give it immortality. That is why you write and for no other reason that you know of. But what about all the reasons that no one knows?”

In every one of my stories and novels, what I know—the people, the places, the subjects—are apparent, but each thing that I know has been disassembled into bits and pieces and reassembled alongside bits and pieces of what I do not know. In this way, I am always surprised. Purpose rides alongside accident. Each successful sentence is made from a fortunate mistake. What I have written becomes something other than a failed representation of what I have known, something larger and truer and, at least for me, more real than the real.

JDS: Your descriptions of land and landscape, specifically trees and water, are prominent in this novel. They don’t fade into the background but feel essential. Elsewhere you’ve referred to Eudora Welty’s essay “Place in Fiction,” in which she writes, “Place absorbs our earliest notice and attention, it bestows on us our original awareness; and our critical powers spring up from the study of it and the growth of experience inside it.” As a writer, how do you think about—or even through—place?

SDZ: I suppose that we’re always thinking through place—that we don’t have any other choice. That is, place is the seat of thought, the context from which thinking begins. A baby notices pain when it accidentally touches something hot, and the baby begins to discriminate between the thing that burns and the thing that is burnt.

What makes this interesting, to me, in terms of the writing process, is trying to, through place, give some sense of how character is formed not simply by an interior (what is inside them) but by an exterior (what is outside them). That is, I think that we use place in very complicated ways. As we separate the self from its surroundings, place give us, as Welty writes, our “original awareness.”

Silas Dent Zobal

Maybe this original awareness defines itself though metaphor? Maybe we define our interiority with metaphors taken from the places we’ve known. I was born in the Pacific Northwest, and I find that landscape haunting, and I think that’s because in its mist and mountains I see the original metaphors by which I defined who I am.

That’s an overly complicated answer. I blame you for this, Jeremy. Here’s the simple answer. I like to pay a lot of attention to the places that I’m in. I like to be outdoors. I’m living in France, and so I’m seeing lots of interesting stuff (Roman ruins, medieval architecture, etc.), but what I like most is getting out to where I can see landscape, water and trees and mountains. Maybe this is because in Bellingham, WA, we don’t have Roman ruins or narrow medieval streets, and so I can see myself most clearly reflected outside, in places that remind me of the archetypal landscape of my childhood—mist on Bellingham Bay in the morning, and wet lodgepole pines, and the first spill of light over Mt. Baker and the Twin Sisters.

Maybe, too, that outside world—the one that the self is defined in antagonism to—reminds me how narrow-sighted I necessarily am, and how controlled and human my range of vision is, and this can give me limited, momentary corner-of-the-eye glimpses of what’s outside my understanding, which is humbling but really exciting, too.

Sometimes I think that existing is an act of ungodly egotism. Sometimes I can feel the strain of it, the constant effort of defending myself so that I hold distinct from the laurels and the dew, from which I am not, in any sense beyond my own insistence, really distinct at all.

JDS: In my review of The People of the Broken Neck I refer to you not as a stylist but as a literary perceptionist. Perhaps this term is only a matter of semantics, but I wanted to make a distinction between on the one hand what I think some readers believe about great prose stylists, which is that they know how to “write pretty,” and on the other hand what I think you and other great stylists are doing, which is much deeper and as much about epistemology and how we know things as it is about formal, aesthetic effects. In other words, your lyricism is not just about singing a lovely song or showing off your chops. It does real narrative work. I guess my question, then, is about your relationship as writer to the form, to language, and to the larger literary effects you’re after in your attention to style.

SDZ: First, what a nice review, Jeremy! What I like most is the review’s thoughtfulness and consideration. In the opening, you talk about the differing styles and aims of John Gardner and William Gass. That’s a good moment. I like both of them—and I can agree and disagree with either side of the argument.

To the degree that lyricism, as in Gass’s literary pyrotechnics, calls attention to itself, it does run counter to Gardner’s “vivid and continuous dream.” Maybe I’m just greedy, but I want both. I want to have my cake and eat it, too. (Likewise, I want The People of the Broken Neck to do the work that one might expect from a commercial novel and a literary novel.) Of course I want to create an urgent and continuous dream. What fun! But at the same time I want to balance Gardner’s dream with moments of lyricism that flicker toward waking us. Self-conscious moments that suggest an awareness of artifice, that question the possibility of any real narrative continuity.

Maybe narrative continuity arises from, to borrow your phrase, our “narrative need” to draw boundaries and reinforce established notions of who we are. And maybe lyricism comes from our “narrative need” to dissolve distinctions—in the way that metaphors seek to dissolve distinctions—between one thing and the next.

JDS: More than any other novel I’ve read recently, The People of the Broken Neck appeals to the reader’s sense of smell. A lot of readers will be familiar with the idea that memories can be triggered by specific smells—and you certainly demonstrate this to great effect, especially with the character Dominick—but even beyond this particular effect, why is your novel so…well, smelly?

SDZ: To an extent, I think that my novel is smelly because place is smelly, too. For example, here in France, it’s common for people to pee in the streets. Alleys and nooks are stinky.

A few years ago, a virus attacked my nasal nerves. After this, I smelled a nearly constant phantom smell—a kind of burnt medicinal baked good. Weird, right? It wasn’t so terribly unpleasant, but it was disconcerting. This faded after a year or so, but afterward my sense of smell wasn’t as strong as it used to be. I really missed it. Without a strong sense of smell, there was less sensual depth to the places around me. “God,” people would say, “smell that?” No, I didn’t. Sometimes this was kind of nice, but I was literally missing something.

I’ve read a lot of fiction with a strong visual sensibility but which doesn’t pay much attention to the other senses. I want my characters to interact with each other with all their senses. I don’t want to sanitize. When I think about smelling things, I imagine molecules entering nostrils. I want the inside and the outside to intermingle. My characters should sniff otherness, should smell the fire before it burns them. They should chew each bit of otherness before they swallow. Maybe otherness, in the act of being consumed, is consuming us too.

Anyway, my sense of smell has come back. Here in France, I’m doing a little dance to celebrate being able to smell all that pee.

JDS: A lot of the smells described in the novel are woodsy smells (“sweet woodsy smell of sawdust,” for instance). So, too, are characters described in wood terms (the children’s faces “like two halves of a split log,” Sarah’s face “like burled wood,” King’s “beech-twig arms”). I thought of this attention to wood—as well as the specificity of trees (beeches, cherry trees, plum trees, dwarf apples, fir, oaks, white pines, ponderosa pines, hemlocks)—as indicating a desire to touch and therefore know something elemental—a desire not only from the characters but also you as a writer. Why do you suppose you find yourself coming back to wood in this way?

SDZ: Maybe because I’m stuck with what I know, and I know a little about wood. Maybe because I grew up in the wooded Pacific Northwest and so, like D. H. Lawrence, I believe “that I am I. That my soul is a dark forest. That my known self will never be more than a little clearing in the forest.” Maybe because I do a bit of woodworking—a dovetailed box, a tiger maple spoon, a mortise-and-tenon bench. Maybe because arborification is a false answer to personification, and false answers are all that I have. Maybe because I have a small collection of field guides with names like Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Maybe because the names of trees are so damn lovely. Or maybe because, when I breathe deeply, the divide between the human and the inhuman smells more like egotism than truth.

JDS: I’m interested in this novel as a thriller—and how you handled working within and against the conventions of this commercial genre. What were the challenges of plot and character?

SDZ: Can I say something that some people won’t like? All stories are conventional. Narrative is a convention. It feels like it governs our lives only because we are so used to it. We are characters who live inside narrative’s clean lines. It can be lovely in there, when the story is kind to people like you. But it can be brutal, too. No matter the narrative, when we are young we struggle to believe in ourselves. As we get older and older, it is harder and harder to remember that who we are is a story.

Fuck highbrow and fuck lowbrow. I want to take pieces and strategies from all kinds of books that fit into all kinds of genres. Commercial work tends toward the plot heavy. Literary work can seem dismissive of plot. What I found most challenging was to believe in characters who were not real. But then the characters took on weight and substance and so it became equally challenging to remember, to remind myself that they were no more real than me.

JDS: I hesitate to ask any easy and expected questions, but I’m genuinely curious about what you’re working on currently. I’d also be intensely interested to hear how you see (or don’t!) politics and contemporary social phenomena influencing you as a writer—or if you think that our current historical moment is pressing itself into your work at all. You’re currently living in France, so I’d also be interested to hear how being abroad changes (or doesn’t!) your perspective on what’s going on here in the United States.

SDZ: I’m trying to write a new novel but I can’t tell you what it’s about. I’m not shy or superstitious or intent on withholding anything. What little I have so far is incoherent. This may be because of the current political climate, which also feels incoherent to me. This election made me angry, and then glum. Doesn’t hatred make you sad? Why do so many of us act like we’re cheering for one side in a football game?

I am oversimplifying. Yes, I am. But I haven’t worked my way out of my sadness yet—so I don’t know the longer-term effect on my work. Short term? It’s slowing me down.

JDS: Thanks for an enlightening conversation, Silas. I think a lot of people are going to read and be deeply moved by The People of the Broken Neck.