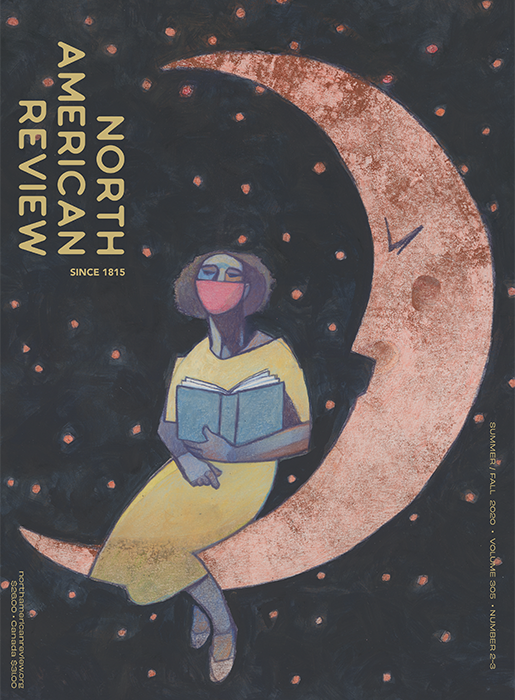

305.2-3 Summer/Fall 2020

Buy this Issue

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

From the Editors

Cuando la Historia duerme, habla en sueños: en la frente del pueblo dormido el poema es una constelación de sangre.

When History sleeps, it speaks in dreams: on the forehead of the sleeping people, the poem is a constellation of blood

—Octavio Paz “Hacia el poema (Puntos de partida)” “Toward the poem (Starting points)”

The needless, widespread suffering—of the pandemic, of unemployment, of violence in the street—has woken some fundamental questions that might otherwise have remained dormant: what is a government for if it refuses to promote the general welfare, much less domestic tranquility? What are political parties for if one of them refuses to argue with intellectual honesty for its principles, if they seem to have traded in those principles for power? What are the police for if they refuse to protect and serve? In the United States 132,000 deaths and still climbing. George Floyd murdered in Minneapolis, Tony McDade in Tallahassee, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, and more and more and countless more. Rubber bullets, tear gas, batons.

Next to these crises, it hardly seems commensurate to ask: what is art for? When the North American Review was founded in 1815, the editors firmly believed it was their duty to discover, promote, and shape a uniquely American literature, anxious to prove their worth against Old World models of artistic excellence. They were the educated elite of Harvard, a handful of young affluent (need it be said “white”?) men, “the wise and the good” who knew exactly what art was for. Their editorial policies were decidedly conservative and cautious, on the question of slavery at best agnostic. Their chapter advances the plot of a long nationalistic narrative of white supremacy and privilege that even now its rapt audience has trouble recognizing as a fiction, something first imagined and then brought vividly, terribly to life.

After living within this fiction for so long, how is it possible to tell another story? After recognizing the fiction for what it is, how is it possible not to try? “When History sleeps,” writes Octavio Paz in 1951, “it speaks in dreams.” This is what art is for: to dream more deeply, more beautifully, more strangely, more justly. If artists are to take seriously the founders’ call to form a more perfect union, they must understand it as an aesthetic imperative to create something different, to see anew, to revise—a job that writers and editors should be well-prepared for. The Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky’s oft-cited technique of defamiliarization is not meant simply to achieve shock value or literary cleverness. Rather, it has the capacity to awaken actual human perception so that we suddenly see through the old myths and tired metaphors we’ve lived by for so long. “When History wakes,” concludes Paz, “image becomes act, the poem happens: poetry moves into action.” Art requires of us a dream from which we must wake to action.

“What drives our reckless behavior?” asks Scott Russell Sanders in his forthcoming essay collection The Way of Imagination. “How is our violence toward Earth linked to our violence toward one another? How can we curb that violence? How can we begin undoing the damage we have caused? What would a peaceful, sustainable, and just way of life look like, and how might we achieve it?” The big questions that haunt Sanders continue to haunt NAR as well. We can’t pretend that the words in this issue offer definitive answers, but they do speak in dreams we hope are stirring and restorative.

⬤

Our current moment of pandemic is echoed in many of the poems in this issue, as in Maria Nazos’s “Quarantine Triolet” (“I ask you: how much longer can you go?”) and Michael Spence’s “An Ill Time,” which takes its title from Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year. Other poems are just as timely, like Charles Harper Webb’s send-up of contemporary conspiracy thinking in “Conspiracies” and Lynne Potts’s take on US- Russia relations in “Dog and Pony Show.” Martha Silano’s “Beatitudes from the Heart of the American Southwest” gives us glimpses of a man “wearing a Make America Hate Again t-shirt” and “Trump/Pence on every third billboard until we reach the outskirts of Hurricane: RESIST.” As an antidote, Diana Babineau’s lyrical narrative “The Brush” lovingly remembers “daily / rituals of hurt,” and in “The Reunion” we float with Alice Friman “in the currents of a dream” and “the warm bath of belonging.”

We’re excited to present the winner of the 2020 Kurt Vonnegut Speculative Fiction Prize, Kate Osana Simonian’s poignant, technology-enhanced Cyrano de Bergerac narrative “The Problematic Douchebag Collective,” selected by final judge Andy Duncan. Two other stories, Rebecca Bernard’s multi-perspective flash fiction “Here in the Future” and Alyssa C. Greene’s formally inventive “Retrospective,” bring us into speculative near- futures while we’re taken back in time to World War I France in Aimée Baker’s “Men Without Faces,” a quiet story of a woman’s husband returning from the front transformed; 1950ssmall-town Nebraska in Jacqueline Eis’s “The Treasure Map,” which recounts a widow’s fraught relationship with her dead husband’s ne’er-do-well brother; and that momentous day in July 1969 in R. Clifton Spargo’s contemplative story of childhood, “Someday Man Will Walk on the Moon.” In another story of childhood, Jeannine Ouellette’s “The Climb,” the young protagonist escapes the specter of violence, and Molly Anders’s humorous “Flight Risk” tells of an attempted escape of a very different kind. Sarah Cypher’s keenly observed “Ghost Town” traces the rapid dissolution of a relationship in a gentrifying Oakland neighborhood, aptly accompanied by artwok by Oakland artist Adia Millet. Roderick Townley’s magical story “Forgiven” follows a poet as he comes to terms with a brief past love affair in France. In Stephen Pett’s “The Keeper's Watch” two grown children attend the execution of their Mormon father, a “messianic magnetic madman,” and in Aurelia Wills’s “The Restoration” an alcoholic divorcee invites two Mormon boys knocking at the door inside her apartment. A new nurse working nights in the psychiatric ward of a hospital in Molly Quinn’s “Service Stars” gets attached to a particularly troubled patient.

In her essay “Chronologies” Rachel Wilkinson interlaces personal history with Walter Benjamin’s flight from Paris to escape the Nazis in 1940, and Richard Goodman’s “Arina” transports us to “the land of painters” in the pre-gentrified Soho of 1980. Many of the other essays in this issue take on masculinity from a range of different perspectives. We follow Leslie Heywood’s preoccupation with three “beings of the male gender” in “Grace Go I”: a dog, a boy, and a man; Joshua T. Anderson explores the gruff masculine violence roiling just below the surface in North Dakota; in “The End of Something” Brandon R. Schrand reflects on the death of a classmate who drowned in the Alexander Reservoir in Idaho; and Rachel Hanson paints an affectionate portrait of fellow river guide “Scary Larry” in “Conscientious.”

Featured in this issue is work by artists Leila Nadir and Cary Adams, presenting their series of eight Microbial Selfies throughout these pages. (Nadir’s essay “Cold War” also appears in our Summer 2013 issue.) Two other writers here present visual work: Raphael Dagold’s poems are accompanied by photographs from his time working in Kyrgyzstan, and Elizabeth Sims’s essay “Taking the Cure” is accompanied by photographs of the natural hot springs in the Eastern Sierras, along with works from her Prima Materia series. Two striking portaits by Joseph Lee appear in these pages, and finally, Lehuauakea Fernandez’s watercolor on page 146 “speaks to the beginnings of the universe as told through the lens of the Kumulipo, the Native Hawaiian procreation chant,” offering the possibility of light and hope in this time of fear and darkness. ⬤