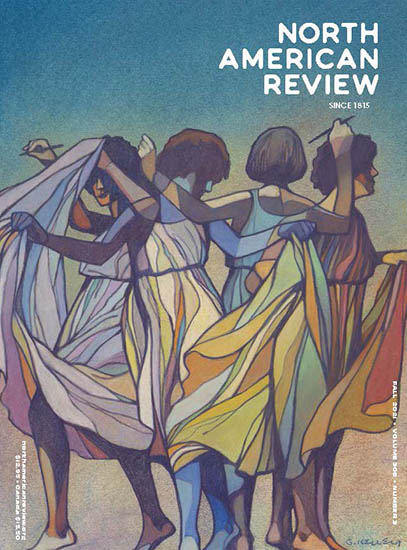

306.3 Fall 2021

Buy this Issue

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

From the Editors

The poem “Interferon'' is set against the backdrop of WWII. The poet, scientist, and Holocaust survivor, Miroslav Holub, writes: “Likewise, cells infected by a virus / send signals out, defenses / are mobilized” and a few stanzas later, describing a quilt shop that converted to a theatre, “In times when what is needed / is a steel cover for the whole continent /.../ In such times men of the world / usually turn to art.”

In the long reach of history, when societies prosper, they create art. Think of Europe in the Middle Ages emerging from the bubonic plague to the Renaissance; trading along the Silk Road helped China’s Tang dynasty flourish; the riches of the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Empires. But what of the empty spaces? The Dark Ages of Europe? The first white settlers in North America? When it is hardest to survive, is that when we need art the most as Holub suggests? Is this a moment when art feels like an extravagance, not a necessity? Artifacts, not art, tell the story.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, along with small businesses, art institutions have shuttered—either temporarily or permanently. Certainly, this pandemic has prevented the creation of art, and as we begin to unmask and breathe out agony and distress, we see so much of what was previously invisible. Graphs break down stark realities: the sick and dead, who has access to vaccines, disparate death rates in communities of color, the burden of childcare on women, the growing divide between the rich and poor, states playing politics with mask ordinances.

And while this is not the NAR’s first pandemic, it is the first time the magazine has been edited, designed, and put together by a team of all women editors. Feminist and poet, Adrienne Rich, moved away from formal verse, while writing her third book and caring for an infant. She said of the process, “I begin to feel that my scraps had a common consciousness and a common theme, one which I would have been very unwilling to put on paper at an earlier time because I had been taught that poetry should be ‘universal,’ which meant, of course, nonfemale.” As we editors labored over this issue together--while taking care of a new baby, working part time jobs, and navigating divorce--the pandemic has illustrated that it is often the burden of women to be in two places at once. At the time this issue is going to press, the Nineteenth Amendment turns 101, and we want to dedicate this fall issue to all women occupying (or on their way to occupying) spaces originally designed for “nonfemale.”

In this issue, you’ll find the results of the 2021 Terry Tempest Williams Prize in Creative Nonfiction. Our judge, Jane Alison, selected “Passive Voice” by Kate McGunagle as this year’s winner. McGunagle’s essay details the agony of revictimization as she takes part in an international trial in hopes of bringing her rapist to justice. Throughout, she reveals how language is both a third layer of victimization and the only way to set herself free. Runner-up Gustav Hibbett’s essay, “Endurance,” tackles racism in the creative-writing workshop and the therapist’s office using an evocative metaphor of high-jumping. Finally, honorable mention Lena Crown’s quiet essay “Pomegranate Girls” explores interstices in a mother/daughter relationship: sexual violence as intergenerational silence. These essays challenge us to confront how American society enables gendered and racialized violence.

By happenstance, this issue contains new work from notable poets living in the midwest. Kwame Dawes’ poem “How to Dream” is both lamentation and celebration for lost homelands, music, and culture. Debra Marquart’s gentle elegy “When the First Love of the One You Love Dies“ moves from a prom photo to “dumb luck recipient /of love’s sweet misfortune, a heart / improved through misery.” Of note is also Kathleen Rooney’s poem that laudes the simple act of smell, and like so much of the work presented in this issue--made during the COVID-19 pandemic--it offers a meditation, a moment of art, during times when art is hard to make, but needed nonetheless.

We’d also like to extend a warm welcome to Emily Stowe, our part-time managing editor who joined our team full time in August. If you’ve interacted with Ms. Stowe, whether you are a writer, artist, or subscriber, you’ve appreciated her calm presence, bold aesthetic sensibility, and joyful sense of humor: the managing editor’s office now features neon textile art and at least one portrait of Jeff Goldblum. We are delighted to have her aboard.

In addition to her experience in the behind-the-scenes business of running a magazine, Ms. Stowe’s background as a visual artist makes her a valuable addition to our team, as she’s the person responsible for initially selecting and procuring artwork. We try to offer a variety of media in each issue, and this time Ms. Stowe focused on collage, photography, mixed-media textiles, and relief printmaking. Each artist in this issue is new to the NAR, and we are thrilled to introduce readers to their beautiful work. ⬤