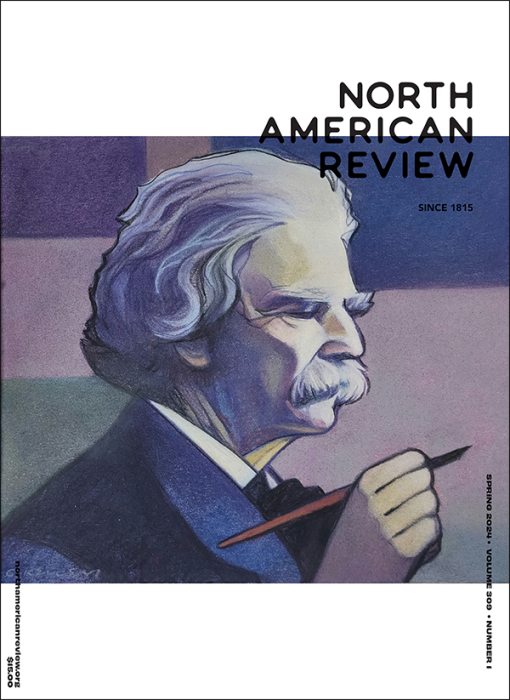

309.1 Spring 2024

Buy this Issue

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

From the Editors

These hints, dropped as it were from sleep and night, let us use in broad day. The student is to read history actively and not passively; to esteem his own life the text, and books the commentary. Thus compelled, the Muse of history will utter oracles, as never to those who do not respect themselves. I have no expectation that any man will read history aright, who thinks that what was done in a remote age, by men whose names have resounded far, has any deeper sense than what he is doing to-day. —Ralph Waldo Emerson, “History” (1841)

Since late last year, the decades-long Israeli- Palestinian conflict has escalated dramatically, to say the least. The October 7 attack by Hamas killed 1,200 Israelis. Thousands were injured and hundreds more taken hostage, leading to massive and ongoing retaliation by the Israeli military and regular exchange of rocket fire from both sides. As of this writing, the death toll in Gaza sits at an estimated twenty thousand. Millions of Palestinians have been uprooted. These are bleak facts. Heavy, heartbreaking facts. From the distant vantage of North America, many impassioned responses by perceived allies and enemies alike have drawn clear political lines, separating those who belong on the side of justice from those who deserve our scorn. Such entrenched enmity assumes the impossibility of sympathizing with the plight of one group without also harboring hatred toward the other. The steady stream of bad news is dispiriting, and the images of death and suffering are difficult to witness—and sometimes to understand. Grief reigns.

In her ethereal poem “Anticipatory Grief as Phases of Moons,” selected by Diane Seuss as the winner of this year’s James Hearst Poetry Prize, Tara Mesalik MacMahon describes the feeling of all-pervasive grief as an elusive thing that “I cannot un-picture,” as “thoughts I cannot unthink,” as something that “I forget to understand.” Inescapable, ineffable, inexplicable. Grief has a way of folding time into itself so that you exist in a perpetual state of memory and anticipation, neither waxing nor waning but doing both at once. When fully unfurled, grief presents us with an emotional palimpsest.

The Holy Land of Israel and Palestine can itself be read as a grief-ridden palimpsest, retaining the social and political traces of the last seventy five years since the First Arab-Israeli War, with all of its greater and lesser eruptions of violence and temporary reprieves. Everything that has transpired before threatens—or promises—to do so again, not as a cycle but as something that has never truly ceased. “The past is never dead,” said the perceptive lawyer Gavin Stevens in Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun. “It’s not even past.” Indeed, the past is alive in Gaza—and elsewhere—bringing with it despair, dispossession, displacement.

Wars have always been concerned about place—who gets to claim it, to name it, to define and defend its borders. Who is included and belongs, who is excluded and does not. No matter how steady the hand that draws their contours, maps are still wishful abstractions that cannot help but distort material reality—too often leading to real material suffering in the real material world. The current conflict is a case in point, reminding us how deeply and inevitably we are immersed in the froth and churn of history. However much we wish it were otherwise, history does not flow in a single direction like a river. It eddies and circles back, crashing against the causes of its own effects.

History is an ocean, not a fable agreed upon, written by the victors. Nor is it simply a checklist of dates and facts, nor the biography of important people doing important things, nor a chronicle of events objectively recorded, as though that were possible to produce in the first place. Rather, history is a cosmos, infinite because it consists of our ever-shifting relationship to the past—and to the present and to the future, for that matter. We would do well to heed Ralph Waldo Emerson’s advice, quoted in the epigraph, to respect ourselves, to consider our own lives the proper text of history, to realize that we all make history every day, whether we want to or not.

Nodding to Emerson’s 1841 essay “The Over- Soul,” the poem that appears on the last page of this issue as a kind of “final say,” John Warner Smith’s “Oversoul,” articulates an apt historical challenge for us in this fraught moment: “I am the history of one and many more. / What, then, have I to say of the past?” What, indeed? As a Black man, when Smith becomes “the slave, the trader, and slave master,” he acknowledges our national palimpsest, pointing to the founding injustice of our American “declaration of freedom” that was written upon “a deed of slavery.”

Emerson’s concept of the Over-soul overrides and encompasses Self and Other, I and Thou, collapsing difference and asserting a fundamental Unity. Within each of us we have access to love, wisdom, virtue, beauty, freedom, truth, justice. Very American. Very idealistic. Emerson insists “that there is no profane history; that all history is sacred; that the universe is represented in an atom, in a moment of time.” In these pages you will read several sacred histories that reveal the universal as they render the particular, the atom, the moment. Many of the stories, essays, and poems focus on specific artists (Salvador Dalí, Robert Burns, Walker Evans) and specific places: present-day Philadelphia, 1930s New York City, post-pandemic Chengdu, mid-century Topeka, near-future Los Angeles, post-industrial Manila. “Stories about places are makeshift things,” writes Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life (1974). “They are composed with the world’s debris.” The task of the storyteller is to render the particularities of the everyday lived experience in a place, not to stand on high and observe it as an abstract system. So, too, history is composed with “the world’s debris” we gather.

You will also find in these pages “Mark Twain’s Playground,” an essay by Matt Seybold, resident scholar at the Center for Mark Twain Studies at Elmira College. In it he describes being immersed in the history of Elmira, New York: “I cannot walk to work, grab a coffee, or take my kids to a playground without wading through the residue of the deep-pocketed political radicalisms of Gilded Age Elmira.” Seybold is alert not only to the landscape as he interacts with it but also as it had once been in the nineteenth century, finding in the debris and residue through which he wades the elements of a new story—new because it is meant for us today. “But my vivid historical imagination only makes me more keenly aware of how those idealisms, which animated Mark Twain’s most-famous works, all written while residing here, have faded, frayed, or ultimately failed.” Contemplating Twain’s idealisms brings the present age into starker relief, asking us to consider how to keep our own from failing. What are our hopes, our committments, our contributions?

Seybold cites William Dean Howells’ staunch belief that Twain should be taken seriously as a writer and thinker: “Mark Twain was literature.” Howells articulates this conviction in more detail in “Mark Twain: An Inquiry,” from the February 1901 North American Review, noting that Twain was always as much a philosopher as he was a humorist, whose “ethic sense of … duties, public and private” compelled him to take on “the graver and weightier things.” In the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, Mark Twain published dozens of pieces in the NAR, including twenty-five chapters of his autobiography, which he had otherwise embargoed for a century. We return the spirit of Twain to our magazine as we confront the multitude of “graver and weightier things” today, including Seybold’s engaging and illuminating essay, Gary Kelley’s portraits gracing the cover and interior, and the publication of a 2025 desk calendar (available now at the NAR store online!) featuring a quotation per day from our nation’s most eminently quotable humorist and philosopher. ⬤