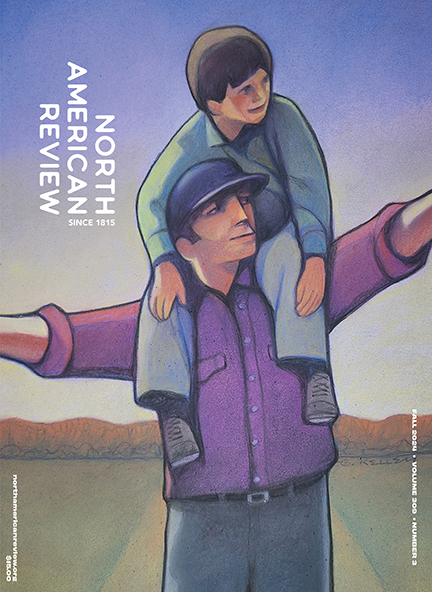

309.3 Fall 2024

Buy this Issue

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

FROM THE EDITORS

Every US election tests the American experiment anew. Are you ready for the one upon us now? What grade should we expect to receive in 2024? Have you studied each side’s ideas on the economy and employment, taxation and trade, immigration and national security? If we’ve learned anything about electoral politics in recent years, it’s that most voters don’t make their selections by analyzing policy proposals. The most reasonable white papers, unfortunately, do not always win.

On the left and the right, twenty-first-century politics has simmered in a bitter stew of antiestablishment, anti-incumbent populism. Power to the People! (As long as they’re our People!) This deep distrust of American institutions includes TV news, big business, newspapers, but especially government itself: Congress, the presidency, SCOTUS. As a result, for better or worse (too often the latter), voters are just here for the vibes. In internet parlance: “He gives Little Dictator Energy.” “She is mother.” Would you prefer the vocal stylings of Kid Rock or Stevie Wonder? The athletic accomplishments of Hulk Hogan or Steph Curry? The wit and wisdom of Tucker Carlson or Mindy Kaling? The vibes could hardly be more different.

Also on offer are two divergent visions of fatherhood. On the one hand, the patriarchal model places the father at the center of the domestic universe. He is the ultimate authority. He must be pleased. He must be obeyed. His ideas of what it means to be male or female must be heeded and performed dutifully. He thinks about the Roman Empire every day. His world, his life, his wife must all be painted the same sickly shade of trad.

On the other hand, what if conventionally masculine characters were tempered by principles of care, empathy, and understanding? A hunter would advocate for gun control. A football coach would sponsor the Gay Straight Alliance. A military man would defend reproductive freedoms. This father supports strong women. He is full of joy. His cheesy jokes must be endured. He gives Big Dad Energy. He is mother.

Which one are you vibing with?

Patriarchy hasn’t changed. It’s trad as ever. You might assume Papa’s got a brand new bag, but he’s only recently begun saying the quiet part out loud. Sometimes he even screams it. He is obsessed with the decline of your fertility. He wrings his hands over depopulation. He worries he’ll be replaced (Meow?) by childless cat ladies. (Hiss!) He explains in great detail his version of The American Dream: a postliberal, authoritarian, Christian nationalist future. It’s not a fantasy. It’s a project.

How should we respond?

Edith Ronald Mirrielees has a suggestion. From 1909 to 1944 she taught literature and creative writing at Stanford. Among her students was John Steinbeck. Appearing in 1921 in the North American Review, her essay “Concerning Fathers” analyzes the image of the father in English novels since the eighteenth century. She describes an index ranging from fool and boor, to insufferable bore, to fullsized tyrant, asking what we are to make of “this brood of blackguards, this monstrous regiment of fictional fathers that whines and blusters and sneaks and bullies.” Concerning fathers indeed. Mirrielees’s answer is simple: mock them. “A flouted tyrant is scarcely a tyrant at all.” In other words, call them what they so obviously are: weird.

This issue of NAR presents a range of toxic, absent, or otherwise dysfunctional fathers. In “Mysteries of the Father” Beverly Burch examines why fathers matter at all: “What is fathering and what essential thing does a man provide?” In his allegorical horror story “Father’s Work,” duncan b. barlow dramatizes a father’s excruciatingly protective love for his son. Dorothy Bendel’s “The Trouble with Angels” describes running away from the abuse of her father into a Catholic shelter for homeless youth. Laura Nagle’s “We Were the Ambers” hints at the specter of a religious father’s wrath. Jason Prokowiew’s “Why We Stole” reveals his violent father’s childhood surviving Nazi-occupied Minsk.

Sophie Collins Arroyo’s essay “What Salitre Cannot Touch,” selected by Toni Jensen as the winner of this year’s Terry Tempest Williams Creative Nonfiction Prize, tells the story of Rafael Cancel Miranda. In 1954, he and three other independentistas took to the United States Capitol building, unfurled the Puerto Rican flag, and fired guns down into the gallery of the House of Representatives, injuring five congressmen. Cancel Miranda served twenty-five years in Alcatraz: “A laminated printout hanging in the isolation cell read, ‘Discipline is systematic training to secure submission to authority,’ a quote attributed to Alcatraz Warden James Johnson.” Alcatraz was built upon these pillars of patriarchy: Strict Discpline. Submission to Authority. Threat of Violence.

One hopes the vibes of Gary Kelley’s cover art “Homegrown in Iowa” may serve as a balm to all this patriarchal rot, showing a literally supportive father encouraging his child to look toward the horizon. To mark sixty years of the NAR in Iowa, all of the visual art featured in this issue is homegrown. Thanks to a generous grant, each artist’s work will be on display at the the Hearst Center for the Arts in Cedar Falls from September 26 to November 27. Support is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Iowa Arts Council, which exists within the Iowa Economic Development Authority. If you happen to visit the gallery on Tuesday November 5, don’t forget: that’s the day of our big test. ⬤