Locust Infestation

I don’t mind the locusts. I have been eating bugs since before it was cool; I was living on them, the summer I turned 34. I measured the cicadas by my age – they came the year I was born, the year I turned 17 and got my license, and then the year I was so hungry, 34, a down-out kind of year.

I say I never minded locusts, but that year I was 17 and the cicadas came, I minded. We had just survived Hurricane Sandy; I made money ripping rotten sheetrock off of the frames of my neighbors’ houses and bought my first car from a guy on the north shore, where things weren’t as wet. It was silver, a little smaller than I would have liked (the back seat wasn’t all I had been hoping for), but the real problem was the windshield wipers. On their highest settings, they couldn’t compete with the fuckers dive-bombing the car while I waited to pick up Evie. She worked at a Pathmark further out, and I didn’t want her walking home alone at night when she got off the train. I would sit in my car, a mixture of anticipation and annoyance bubbling up from the pit of my gut.

How satisfying those bugs were, on an empty stomach, for an angry heart.

Those nights were what I had been waiting for: Me, with a car; me, newly taller, newly stronger, newly devirginized. I wanted every night to be like that first one, but instead of staring into my eyes and kissing me with a smiling mouth, like that first night, she would stare at the cicadas through the windshield, fascinated and horrified. I would try to kiss her at her door, get her to sneak me past her sleeping parents, but instead she would do a terrified skip-hop-run towards the house, jumping away from the bugs as they flew at her. I could hear them crunching under her feet and I watched as she ran, and I stared at her body, of course I did. By the time I made it to the door after her she would give me a quick, violent peck on the cheek and dash inside. I watched those dimples on her back, above her jeans, that always showed when her shirt rode up. Then the door would close, and I would go home, swatting bugs, angry with them, frustrated, if you know what I mean.

When I was 34, I tore at them with my teeth. I don’t want to get into how money was tight, how I heard that Evie and every other girl I thought I loved had kids by then. How high school friends were so easily found on the internet, smiling in everything from book jacket photos to Times wedding announcements. How I owned exactly three t-shirts and a pair of pants. How satisfying those bugs were, on an empty stomach, for an angry heart.

I don’t want to get into how I pulled myself up out of that hunger. It wasn’t a Rocky montage. It wasn’t because I pictured Evie waiting for me on the other side of gnawing lack and poverty. It was because that’s what humans do. We survive. Without a lot of thinking. Without a plot line or sappy movie ending waiting for us on the other side.

I see my neighbors now struggle with the locusts. The crops are gone; we are all now on a low carb, high protein, bug-based diet. Keto had nothing on this. They eat them and try to catch them and gag all the time. But they do eat them, and they do trap them, and they need them. They are human, and they try to survive. I laugh now when I think of Evie hopping away from cicadas. Cicadas would give us some variety, I think. Cicadas are a bit heartier than these locusts. I laugh, and then I pause, and then I take another bite.

Recommended

The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

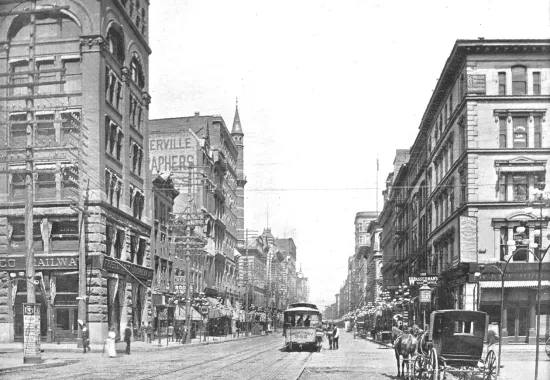

A Picture of Stack Lee

Crossing Paths