From Poetry to Fiction: The Imagined Self

Poetry was my first genre. The pleasures of metaphor, compression of expression, and the controlled line appealed to me in ways that prose did not, and when I first began writing—and then publishing—I never thought I would write anything but poetry. Of course, critical essays and book reviews were part of my work, but those always felt as though they came from a different quadrant of my brain. Poetry was my genre.

My first poems were also very personal, and my early books, taken together, are almost a memoir in verse. Those poems felt urgent, needing to be written before I could do anything else creative. Maybe it was therapy; maybe it was self-discovery; maybe I was using my own life as a way of understanding what cultural imperatives do to an individual personality. Maybe all of the above. I don’t know, but what I do know is that I was also feeling my way through my own narrative, in tight, often quite short, pieces.

Writing about the self has its limits, though. By the time I was writing my most recent book of poems, The Gold Thread, I was writing about historical people and situations, using characters and situations from my scholarly work in Early Modern British literature. The shift happened during a trip to Wales one summer. I had a grant to investigate the recipe manuscripts left by seventeenth and eighteenth-century women in the National Library at Aberystwyth, and my intention was to get as much information, for my teaching, about domestic life from that period as possible. And I learned an enormous amount—but what came of my time in Wales was not an academic book but a series of poems about those women, some largely imagined and some based almost entirely on details that they’d recorded. That experience changed my poems.

My genre, however, was also ready to change. The poems got longer. Then poems became parts of sequences of poems. I had always been a poet who needed an idea for a book in order to frame individual poems, but the book suddenly seemed like a long poem itself. Then a friend, after reading those recipe-manuscript poems, told me that I “really should write a novel.” That comment must have festered somewhere, because not long after, when I was in a bookstore, at the historical novels shelf, I chose what I wanted, then turned to my husband and said, “I’m going to write a novel.”

That night, I opened the laptop and began writing the book that became The Altarpiece. I already knew, somehow, that my main character was a young nun under Henry VIII (I had been doing quite a lot of scholarly research about these disappeared women), and that she was about to be evicted from her convent at the beginning of the Reformation in England. Beyond that, the writing had to tell me what would happen.

And it did. As a poet, I was a fitful, stop-and-start writer, working in small episodes of furious writing throughout the day. As a novelist, I now write in the evening—every evening—in one long sitting, usually working until my brain wears out. This change happened suddenly and I didn’t plan it, except for that first decision to put fingers to keyboard after dinner. I think about the novel in progress off and on all day, and I often research specific details of clothing, medical practices, development of weaponry, and food availability during the course of a day. But the writing always happens in one session—and it (almost) always happens in the evening. I’ve now finished the second novel, City of Ladies, which will come out in October 2014 and am currently revising the third, The King’s Sisters.

Do I still write poetry? Yes, though not as frequently as I did. And I still write critical prose, as well as blogs and short essays for my own website. Those can happen any time of the day. Maybe I need the stillness and peace of the darkness to hear the voices of characters, the leisure to let them do what they must. Maybe I need that stretch of time before bed to give the characters time to plot and plan.

In the late stages of writing the third novel in my Cross and Crown series, I find, surprisingly, that in fact I may be coming back to those personal concerns of my early poems—the lives of women and how they are shaped by the force of personality against circumstances—but in a new, fuller and less personal way. And that gives me a freedom from self that actually allows me to explore many selves more completely. Poetry and prose seem to have dovetailed, as have my creative writing and my scholarly reading, so that I feel less as though I have left poetry and autobiography behind than that I have built them into another, larger imaginative world. Do I still write poetry? Yes, and I probably will until I stop writing altogether. In my fictional characters in historical settings, however, I can create an entire world of women—and men—who are not me, but who think and feel as completely as I ever felt the pressure of my own life in those early poems.

Sarah Kennedy is the author of the novels The Altarpiece (Knox Robinson 2013) and City of Ladies (forthcoming October 2014). Her third novel, The King’s Sisters will be released in August 2015. A professor of English with at Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia, Sarah Kennedy holds a PhD in Renaissance Literature and an MFA in Creative Writing. She has received grants from both the National Endowment for the Arts and the Virginia Commission for the Arts and is currently a contributing editor for Shenandoah. Sara is featured in issue 294.3/4.

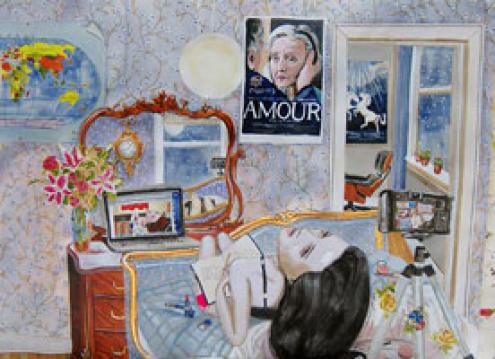

Claire Stigliani (b. 1983) is a drawer and painter known for her works inspired by paintings, photographs, magazines, posters, YouTube clips, literature, performance and plays. These works explore the act of watching and being watched and blur fiction with reality. Her recent shows include The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, The Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, (WI), The Dean Jensen Gallery, Milwaukee, (WI), RussellProjects, Richmond (VA), and the Jenkins Johnson Gallery (NY). She is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art in Drawing, Painting, Printmaking and Photography in the School of Art at Carnegie Mellon University. http://clairestigliani.com/drawings.html

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings