To Slip the Cable Free: Why I Wrote an Epic Poem from issue 295.3

A three-week bout of vertigo struck me when I moved to Maryland in 2011. I found a surprising remedy in running. Also unexpected, the state’s hilly trails, glittering with schist, furnished a sense of adventure I had not known since college. Gradually, my vertigo-turned-verve desired its own story. I imagined a girl runner who loses her house to foreclosure and must save her family and community after a speculative collapse of the oil economy. Yet when I tried to pen the story, I could not get far beyond sixty pages.

Prose felt so plodding in contrast to the running girl’s pace. My narrator creeped around like Tom Jones in Henry Fielding’s eighteenth-century novel. The narrative sounded diary-like, even without the datelines.

In spite of point-of-view shifts and populations of characters, novels even today sound solitary to me, a voice in the reader’s ear, or self-talk while a narrator recollects the past (or, weirdly, the unfolding present). There is a speed governor on how fast one can whisper or recollect. Style should match theme—and I wanted my runner to race!

Around that time, looking for a book to read to my twelve-year-old son, I shelf-picked Robert Fagles’s translation of The Odyssey. Reading together was a dying ritual; Miles was ready for longer novels with more adult themes, but they simply did not hold up to nightly read-alouds. Even Dan Brown’s thrillers are hard to sustain over hundreds of pages. Crafty old Odysseus was my last gamble.

We read the entire epic with joy, laughing over anaphora such as “Dawn and her rosy red fingers” and the bard’s almost clockwork praise of “the choicest cuts of meat.” My voice found a rhythm, partly chanting, partly a gruff general listing of the details of his campaigns and journey home:

They slipped the cable free of the drilled stone post

and soon as they swung back and the blades tossed up the spray […]

so the stern hove high and plunged with the seething rollers

crashing dark in her wake as on she surged unwavering,

never flagging, no, not even a darting hawk,

the quickest thing on wings, could keep her pace […]

Only now, after writing an epic poem myself, do I fully appreciate how this passage would differ were it to appear in prose. The epic catalog rolls forth, each description, each line another wave. Many novelists would have edited out the alliteration and assonance. The original sentence is much longer, and even this redaction would be broken into three or more independent clauses in prose—or trimmed by half because, however pretty, it may not push the plot forward. But poetic license in an epic never sounds false since, after all, it is a poem. The same elements that would have sounded false and self-indulgent in prose make an epic poem “the quickest thing on wings.”

Without much thought for the long odds of publishing an epic poem in today’s marketplace, I began to write my adventure about the girl runner in verse. I set myself the constraint of using pentameter, and in revision, tried to reword each line into iambs.

Almost every draft now sailed along. (Maybe the Muse is grateful for the invocation that starts every epic!) Sure, there was long labor, and the patrons of Baltimore coffee shops eyed the madman tapping out beats of ten. But each line of ten beats built on the next. What I am trying to express is that meter is NOT just a nod to tradition. Something else has been forgotten in the predominance of free verse.

Meter has its own hand in narration.

As prose writers try to allow characters their own voices, just so the meter spins its own yarn. Iambs, like any metrical foot, really describe a relationship between neighbors; two syllables sound longer or stronger in relation to each other. As a result, writing in meter must be as organic as animal husbandry.

Shakespearean actors rely in a similar way on meter’s aid. Guthrie Theater veteran Bill McCallum told me, “It's much easier for me to learn verse lines than prose lines, even within a Shakespeare play. Once you get a feel for the way the meter works, the necessary right word comes naturally and falls comfortably within the speech. If you get the wrong word, it feels wrong and interrupts the flow of the speech.” How many times I, too, nixed the wrong word, line, or plot whim because the meter barred admission!

I understand why the epic form largely died out with the industrial age. Why would gritty realism—Dostoevsky? Dickens? Sinclair’s The Jungle—try to sing? The elements that define the form scarcely fit; history and the news have taught us, perhaps rightly, to cast a critical eye on adventuring heroes and divine intervention. (At the same time, I thought there must be an approving god when my book, after rejections from agents and publishers, found its proper home with Ilium Press, a small, Spokane-based indie that majors in original epics.)

The epic is worthwhile precisely because it is not a diary. It is intended for a community gathered to hear what they most need in the face of colossal, inhuman forces. That is why the long monologue is such a natural and rousing feature of the genre. In good part, the adventure belongs in verse in order to be remembered. The audience—and my preteen son—could sit through 500 pages of The Odyssey for the very reason that it runs and sings.

E.C. Hansen’s poem “Shopping at Super-Target with Death” appeared in the summer 2010 issue of North American Review. His first book, The Epic of Clair, is forthcoming in September from Ilium Press.

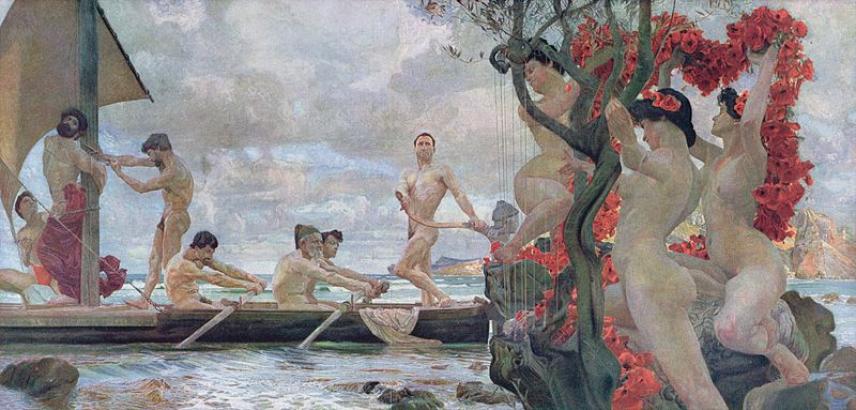

Painting by Otto Greiner (1869-1916)

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop