On writing: "Plenty, Hay" from issue 299.1

I like to think of my poetry as non-fiction, and in large part it is. I often struggle with ideas or images which are not, strictly speaking, part of what actually happened. Of course, this is a foolish response: what works in order for the poem to construct a more viable connection with the reader (or subject matter), or access a higher order truth, or in some other way makes it a better poem is what ought to matter. Nevertheless, I continually confront myself as a writer in these circumstances, and then frequently confront the poem as well. I am happy to report that I have gained efficiency in this process, though I doubt I will ever conquer it entirely. Perhaps that is what is best for me as a writer, that urge to stay with reality as my experience is what defines to some extent my voice as a poet.

Still, it makes me inordinately happy to write a poem that does not require struggle in this way, as in this poem. Though I recognize how valuable conflict is to writing in general, there are times when my writing has more value in its verisimilitude and quietude, even when a deep conflict resides within it. I like to think this is such a poem, or at least, I experience it as such. It also reflects my desire to make poems which I imagine to reside somewhere in the realm of the accessible. I realize this is not always a popular decision, and I have been derided for even considering the idea. Nevertheless, for me this poem is strongest in its simplest moments, and so too is my writing in general. I have a strong urge to craft things that relate to a common experience and in language with which this experience can be commonly shared. I have no objections to poetry that strives otherwise, and I fail just as often as I succeed.

That said, I think this particular poem works fairly well in that space. It also shares some common themes with a lot of my writing: the accessibility, the alignment with experiences more concrete than imagined, and also a sense of rural life, of evocation of place and people and time, and a (rather) simple narrative. I write quite a bit, and a large portion of it is me exploring the edges of what made me, me. In my case, so far my answer has been something like the people I knew, the places I lived, my family, and my sense of self. I don't suppose any of that is different or groundbreaking, but I think in some way it’s what makes me happiest as a writer: that, of course, these experiences are what has made most of us ourselves. This is a long-winded way of saying “I write about what I suspect most people write about.”

This poem is also aware of those which have come before it on the same subject. I love, for instance, Carruth's “Emergency Haying,” and a few poems by Joyce Sutphen are especially present as the poem opens. The first important moment for me as a writer happens when the poem turns to confront my ideas about what writing (about haying here) is and means. I am eternally grateful to my writing for this, allowing me an outlet by which I can work with and work out my own struggles, especially when those struggles are with writing.

Of course, there are many other services my writing provides me with. For example, this poem allows me to be ashamed in a somehow less shameful way, and to express it as if to almost make amends for my failure. I admire the bravery of writers who are able to reveal incredible things about themselves which no one would ever bring up at a party, and most would never share even with their spouses or family. It’s not a voyeuristic admiration; it’s cathartic and jealous. Somewhere in all of us—it has been my experience—are things we are deeply afraid of admitting to anyone, even ourselves. Its not hard to see in this poem that it is too late for me now to express and reveal this shame to anyone who might have mattered on a personal level, but the revelation for the self is a powerful thing, and I am better for having revealed it not only as a poet, but as a person.

Poetry is an ancient institution, and so it can be difficult to wrestle with as a poet, and easy to feel insignificant or powerless. The truth for me is that we as writers, reader, and editors get to define what we want the institution to become, which is a far more powerful thing than our perceptions of how important we might be to what it is now, or was in the past. I like to think each of us, as we read, write, edit, purchase and interact with poetry, could be in some way conscious of this. Not afraid, not obsessed, but aware. Certainly in my own writing, this is my grandest pursuit. At least, it is for now.

William Stratton, I currently live and write in Newmarket, New Hampshire, where I teach for the University of New Hampshire. My first full length collection of poetry, Under The Water Was Stone, is due out in May of 2014. My poems have been previously published or are forthcoming in: The Cortland Review, 2River, Pif Magazine, Best of Pif Magazine, Untitled Country Review, Spillway, North American Review, and The Lindenwood Review, where my poetry was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

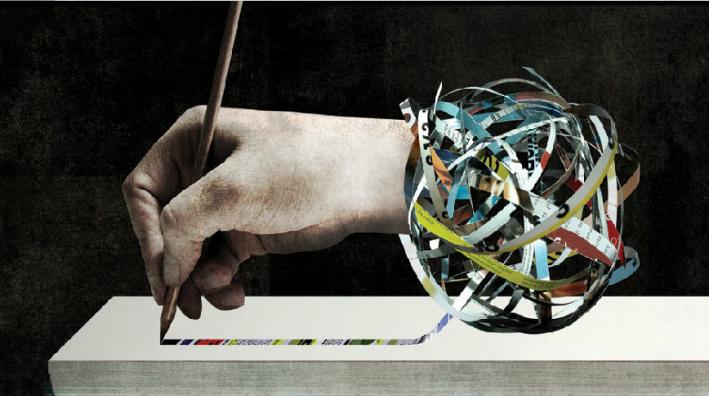

Anthony Tremmaglia is North American Review‘s featured artist in today’s post. He is an Ottawa-based illustrator, artist, and educator. His clients include WIRED, Scientific American, Smart Money, HOW, and San Francisco Weekly. His art is available at art is available at Saatchi Art.

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings