Writing for Dummies

I am mostly—most conventionally—a newspaper columnist and film critic. I have done this sort of work for just over 30 years now; before that I played ball and guitar in punk rock bands and worked strange jobs that sound more romantic in hindsight than they in fact were. I am a product of a land grant university who disappointed his mother by walking away from law school after two years.

I have also written songs and stories, and here and there a few poems, which I keep meaning to gather up and send off to people who might tell me if they are good or not, who might collect them in a chapbook I can give away to my friends.

When I am asked to talk to students about “my writing life,” I generally tell them I feel I was as unlikely as anyone to have a “career,” and that I consider myself fraudulent and inadequate even to the modest tasks I am asked to do—to produce a few cogent lines of English that won’t embarrass my employers.

I tell them it is hard for me; that no one is more conscious of how imperfect my work is than I am. I know every clumsy word, every rhythm, every banal expression, every forced unfunny joke. All I can offer in my defense is that I’m doing the best I can. I try very hard to do good work. And that I respect my readers.

And that is the truth—though only part of it.

What I don’t tell them is that I am also a little brave.

Most people probably agree with the famous basketball coach’s assessment of writers: It’s no big deal, most of us learn how to write in the second grade and then move on. Reading and writing are fundamental skills, of considerable benefit in some lines of work, but nothing that serious people ought to think too much about. You master a vocabulary, you ought not be too damn enthralled by mere words. There is too much real work to be done.

I suppose I have always been blighted in this way: I am distracted by the gleam and nap of words, by the way they can be made to dance and sparkle and glow with animal ardor. I find it impossible to take them for granted, or to accept that one is as good as another, even when what you are making is basically a mortar for advertisements.

There are no synonyms, Flaubert knew, only the right word and a hundred million wrong ones. While expediency might call for a quick six inches, I can’t do that. I can fill the hole, I can write to a specified length, I can even murder my darlings—but I can’t do it quickly or ruthlessly without considering how I might have done it better.

I am word-bit, obsessed with the mouthfeel and tunefulness of them. For me, a chapter of Fitzgerald is like a spill of glitter on a moon-burned beach—there is copper and bronze amidst the gold, and some of the jewels are paste, but it is all treasure. A sentence of Henry James can be like a long, winding tunnel negotiated by torchlight. There are baroque grottoes on either side, it isn’t difficult to become lost. Hemingway’s words jab and pound; working the body before going off white in your head.

I love what writers can do, the especial mind-to-mind transmission from writer to reader, the genuine telepathy that might be achieved.

What is essential, once you get past the utilitarian stage where you’re using words as glyphs and you begin to see their mutable auras, is the rhythm of writing. It is so much like music that some people who write for a living or aspire to write for a living are simply deaf to it. The ear is the chief organ. It commands and instructs. It is all you need, it damns you when you slide off-key, it reminds you of how far short you fall of the sound in your head.

And it’s frustrating, because you rarely catch the jazz the way you think you should and because the tone-deaf don’t much care either way. Most people think that newspaper columnists write about the issues of the day, or how much they hate certain kinds of politicians, or about the life lessons they learn when their kid finds a turtle in the backyard. They think it is about gossip or a national consumption tax or how people aren’t as good these days as they were in the way back.

No.

The dirty secret of some newspaper columnists is that—for some of us, at least—our putative subjects are just excuses to write. This is how it is for me; I have a few opportunities every week to blow a solo in the semi-public of a newspaper’s pages. I can try stuff out—and I can fail. The nature of this dead tree technology—this fish wrap—is it is forgiving; you mess up and in a week it’s forgotten.

Some approach it differently: there was a much-beloved columnist here who bragged that he rarely spent more than a few minutes in the morning on his columns. I don’t believe it, but that is what he said.

Others probably think of themselves less as writers than as informers or maybe even entertainers. I don’t know about anyone but me, but I write deliberately and cut far more than I submit for publication.

And I don’t expect everyone to get it; people get into all kinds of things—into Bix Beiderdecke and white pinots and internal combustion engines. We all have our enthusiasms. I’m just trying to explain mine.

But you must remember the trick is not in the feeling or the seeing. It’s not in the reception of sensation. A tuning fork is not a song. Sincerity of emotion, pain of creation, hours with a thesaurus and a rhyming dictionary, they don’t matter much. Maybe they don’t matter at all.

Anyone who writes for a newspaper ought to keep in mind that there are all kinds of audiences out there—and it’s only the most basic one that’s reading for mere information. If you’re a columnist, you are compelled to at least attempt to stimulate thought. And if you’re a writer, then you aspire to affect the human heart through what you ought not be ashamed to call your art.

So what if it’s cooler to pretend that it doesn’t matter? That you’re just one of the boys who got a little lucky and that you don’t take it all that seriously? Fine—it’s safe to be a cynic, to snark, to revel in the cheap and easy, to court the mob by assuring them they’re the best, most sensible sort of people, to dismiss that which you can’t bother engaging as pretentious.

I don’t do that, though. I freakin’ aspire. I write columns the same way I try to write poems, to write songs. To me it’s all the same thing. I try to find the key, and the rhythm.

And I work hard at connecting with whoever may be attending on the other side of the wall.

I know there’s probably no one there. But I keep on anyway.

Philip Martin is a columnist and the chief film critic at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, as well as the “monkey in the nose cone” of the blood, dirt & angels blog (blooddirtangels.com). A finalist for the 2012 James Hearst Poetry Prize for his poem “Ray Chapman, Killed by Pitch August 16, 1920.” He is the author of two collections of essays, The Shortstop’s Son and The Artificial Southerner. A singer-songwriter who won a national contest in 1981, he recently released his first solo album, Gastonia. Over the past 20 years, Martin has won more than 30 regional and national journalism awards. Martin lives in Little Rock with his wife and editor Karen and three rescued terriers. Philip's poem, "Ray Chapman, Killed by Pitch August 16, 1920," was featured in the 298.2 issue.

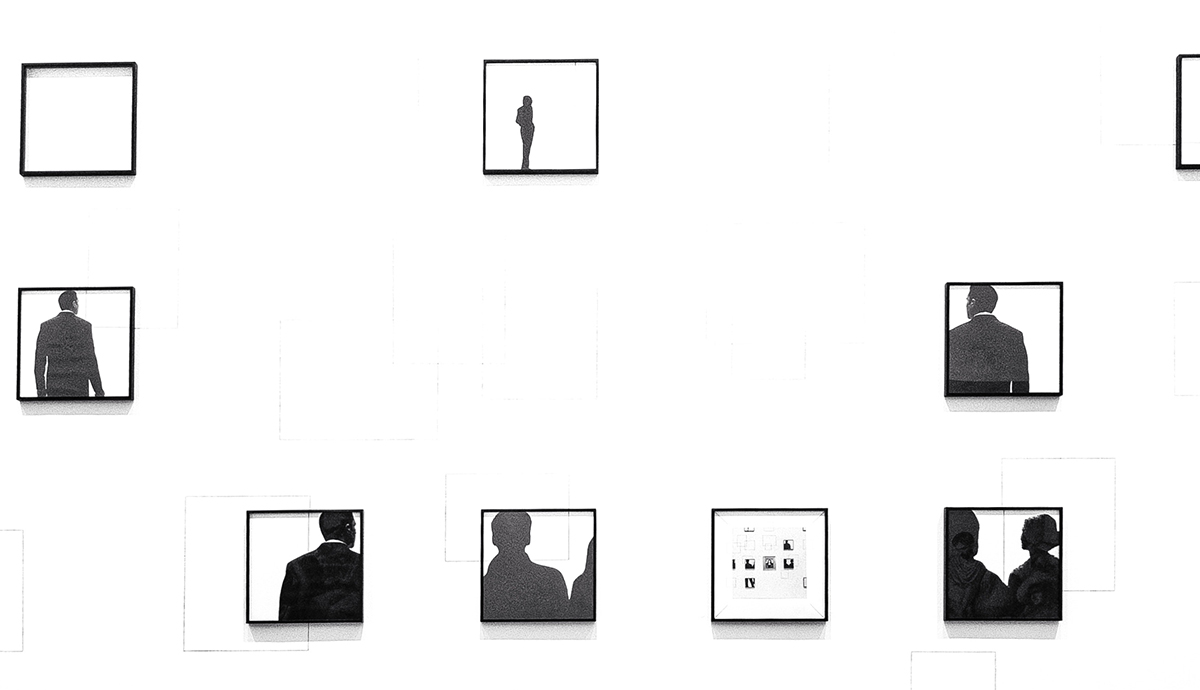

Top photo by Vlad2000Plus

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop