Arrow in the Neck

There was a right way and a wrong way to everything. From the time he was seven years old, Logan Fife had lived his life by this dictum, which had been drummed into his head by his father, Gerald Fife, second lieutenant, United States Marine Corps. And even though his father had been killed in Vietnam in March of 1967 when Logan was fourteen, he continued to live his life by the code of discipline his father had seared into his being through carpentry lessons, hunting and fishing trips, and summers of intense physical labor. Four more years of Catholic schooling only deepened the imprint.

When Logan married Jean Anne Bell two years out of high school and took a job as a trainee at the Northern Wyoming Smokejumper Center, he became even more focused and exact, more confirmed in his adherence to discipline. When his first two children, Jill and Melissa, came along, he molded them with fierce dedication to doing things the right way. No whining, no excuses, no escapism. He taught them well and with utmost respect and affection but never compromised for the sake of peace or in the face of tears. They became, as it was said at the Smokejumper Center, troopers.

Once Logan Fife’s son, Scott, joined the family, it appeared that this boy would be a crowning testimony to the ethics of his Marine Corps grandfather. Scott’s grooming was intense, enthusiastic, and proud, and was carried out without compromise for the first fourteen years of his life.

Scott was sixteen before he began to waver. He was kicked off the football team for missing too many practices. He was arrested for shoplifting a barbecued chicken from the rotisserie at Safeway. He was caught swimming naked with twin sister blondes in Sheridan’s municipal pool at 2 a.m. These aberrations did not surface all at once; they arced across his last two years of high school and triggered severe reprisals and punishments from his father. Scott took the punishments in stride, exemplary in his contrition and in his amended behavior. Logan Fife, in spite of his anger, his embarrassment, and his disappointment, could see that this was not a bad boy, not an evildoer. The boy’s mother had stood up for him also, and stood up to Logan in pointing out the bright side of her son’s track record as a varsity wrestler, a community volunteer, and as a kid who cared about everyone from babies to the elderly.

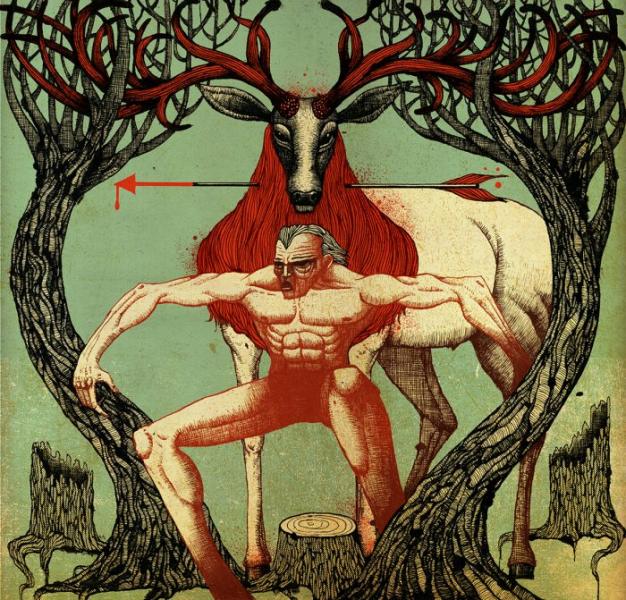

Logan knew Jean Ann was right but had to fight furiously with the demons of his own standards to keep from savaging his son with harsh words and punishments. To have his son step out of line in what seemed such a cavalier fashion galled him to the quick. More than once he had to drive to the health club and play racket ball until he was ready to vomit before he could find the calm that loving his son called for. He found no solace in praying about the lapses in Scott’s behavior. He preferred to chop wood instead, splitting the logs in perfect halves with an axe honed sharp as a guillotine. He had to draw an arrow to the maximum pull his bow would allow and see it pass through the chest of a deer, the fletching flickering as the arrow sailed into the dark border of trees at the edge of a meadow and the deer dropping to the ground like a box of rocks. Even that exactness was not always enough to set the scales in balance. Not until he had skinned and gutted and carved the deer into steaks and ground parts of it into long, even streaks of jerky, and fitted the wrapped steaks into the freezer in smooth, orderly stacks was he able to feel the anger lift.

For the first two years after Scott graduated high school, Logan Fife was given, as though a gift from the gods of temperance, a reprieve from any problems with Scott. The wheel of fortune seemed to be spinning in reverse. Scott got a part-time job at an REI store and enrolled in Northern Wyoming Community College. He began dating a girl from Rollins, who had aspirations of becoming an orthopedic surgeon, and he and Logan hunted deer and went trout fishing at every opportunity.

The second summer Scott was out of high school he spent time on a district fire crew, battling blazes in Wyoming and Montana and creating a reputation that was music to his father’s ears. They never talked about Scott’s pursuing a career as a smokejumper, but Logan Fife nurtured a secret hope that he didn’t share even with the boy’s mother. Though he was radical in his rejection of anything he considered “pipe dream nonsense,” Logan had a streak of superstition he allowed some play in his character. There was always that little gadfly of perversity in life that you had to factor into your assumptions, like the impish musician in Fiddler on the Roof. He hated that little fucker, but he knew better than to deny the fiddler’s existence. So he let things ride, and welcomed the uplifting steadiness he was seeing in his son.

Scott Fife got his first DUI a month after he turned twenty-one. His father’s close friend, Cal Kroomquist, a lawyer who specialized in Wyoming DUI violations, kept Scott out of jail by challenging the reading of a breathalyzer test and by negotiating some community service for Scott. Logan considered taking Scott’s car away from him, but Jean Ann talked him out of it, arguing that Scott needed the car to get to work and school. Stranding him that way just wasn’t worth the risk. Logan agreed but still gave the boy a lengthy tongue-lashing.

For the next six months, Scott showed no signs of resentment toward his father. They went grouse hunting a couple times and to a gun show in Montana. Nothing was said about the DUI, although Logan stayed away from the country bars they sometimes visited on their outdoor trips. One night near Red Lodge, Montana, they met some loggers at a café, and the loggers talked them into joining them at the Hunting Lodge Bar across the street. Logan got excited by the camaraderie, drank more than he was used to drinking, and had to have Scott drive him back to camp. It was encouraging for Logan to see Scott drink only two beers in two hours and not be drawn into the reverie.

Logan was on a fire in Colorado when Scott got his second DUI.

Over a smoldering bed of campfire coals deep in the Big Horn Mountains, Logan listened while his son talked.

“It’s not as bad as you think, Dad. That first one I was right on the line on the breathalyzer test. It could have gone either way. And the cop was clearly out to hammer me on the second one. You should have heard the way he talked to me.”

Logan slid a spatula under the two trout he was frying. In the waning light, the shine of their skins and the red flicker of the slashes on their necks did not have the usual calming effect on him. “You’re making excuses. A DUI is a DUI. And if you think Cal Kroomquist is going to get you off a third time, think again.”

“But I wasn’t being reckless on that second one. I had no idea the taillights were out on Blessinger’s car. That’s why we got stopped.”

Logan slid the fish onto two plates next to a bed of fried potatoes.

“I’ve never had a ticket,” he said. “Not even a parking ticket. You’re a time bomb waiting to happen.”

“Maybe you’re luckier than I am, Dad. We’re not the same person.”

“Luck has nothing to do with it. It’s choices, and you know it.”

“OK, I made bad choices. But I’m not a criminal. I can change.”

Logan looked at his son—the bright, intelligent eyes, the square jaw, and his mother’s thick blonde hair. So much going for him and him jeopardizing it all. How did this happen?

“You can talk change,” he said. “But your words don’t hold water. We’re going to have to try something else.”

“Like what?”

“You can’t live at home any more. You need to be out on your own.”

“I can’t afford to do that. I’ll have to quit school. How can you . . .”

“Because I have to. Because you’re destroying my relationship with your mother, and with you.”

“I don’t see what this has to do with Mom.”

“It has everything to do with her. That’s what family means. ‘We’, not ‘I’.”

“Then let me stay. I can make things better. I’ll stop partying.”

“I’m giving you two weeks to find your own place. You’d better start beating the bushes when we get back tomorrow.”

Scott finished his meal and scraped the fish bones off his plate into the fire. They flared briefly, then shifted into the coals, their delicate tips glowing.

“I’ll prove you wrong.”

Logan didn’t answer. He was staring at the dark wall of pines bordering the north edge of camp.

Eight months later, at two o’clock in the morning on a crisp, full-moon night in early October, Logan Fife was awakened by the harsh jingle of his landline by a call from the Sheridan County Jail.

“Is this Logan?”

“Yes it is. Who’s this?”

“Jeff Redding.”

“Jeff! Good to hear your voice. What’s up?”

“We have your son in custody here at the jail. Brought him in about forty minutes ago. Thought I’d best call you as soon as I could. The jail is really crowded tonight, so I’m checking to see if you want to come get him.”

Redding paused.

“Course he could be back in here once he goes to court.”

Logan sat up on the edge of the bed, could see the moon between the curtains, arresting in its luminosity.

“What’s he in for, Jeff?”

“DUI. And leaving the scene of an accident. He didn’t really go far; just wandered down the street from the taco truck he glanced off of. Sitting on the curb with his head in his hands when we got there.”

“Is he OK?”

“He looks fine to me. He asked me not to call you. Said he’d be fine if he had to stay the night.”

“Was anyone else hurt?”

“Nope. The Mexicans who own the taco truck must have been sleeping in the park at the end of the block.”

“Was Scott alone?”

“Far as we could tell.”

“Damn it to hell, that’s the . . .”

“What’d you say? Lot of noise down here.”

In the brief hiatus before he spoke again, Logan Fife sensed a void opening in the night sky and the moon pulling back, dimming, shrinking, but when he looked again, it was still looming large, burning with a coppery glow. He knew the answer to the deputy’s question before the question came.

“So do you want to come get your son, or do you want us to hold him over night?”

“I . . . I think he needs to stay there, Jeff; at least for tonight.”

“We’ll go ahead and put him in the communal cell then, if that’s OK with you. The singles are all full, doubled up actually. Not sure what’s gotten into people tonight.”

Logan tried a halfhearted quip about the full moon. The deputy muttered something about werewolves; then said he had to get going, he had a bunch of people to book.

“You can come get him any time after eight in the morning. That’s not far off.”

“Not far,” Logan said, but the figure of his sleeping wife on the far side of the bed seemed a galaxy away.

The telephone woke him again at 4 a.m., and he was told when he answered it that he needed to come down to the jail right away. Jean Ann was wide awake this time and said she was going along, but Logan sensed he shouldn’t let her. They argued intensely for a few minutes, but Jean Ann would not accept waiting for him to come back—she’d go in her own car if she had to. Logan told her to go ahead and get dressed but made her promise that she would stay in the courthouse lobby while he went up to the jail to check on Scott.

The seven-year-old Lakota boy feinted right, keeping his dribble, then cut left, circled behind Cody Birch, dribbled under the basket, glanced up at the bare hoop, dribbled back out to the far end of the cement pad, spun, dribbled past Cody in a burst of speed, looped behind the rusted pole holding the backboard and rim, dribbled straight at Cody, then stopped five feet away and stood bouncing the ball like he was tattooing Cody’s face with it.

The Lakota boy had not known Cody long, did not expect him to charge. So he was totally surprised when the top of Cody’s head speared into his chest, the ball flying off to his left, and then he was falling. He felt his shoulders hit the cement, but he somehow kept his head from snapping back, relieved, but only for a few seconds, because close-fisted blows were peppering his neck and face. He managed to cross his forearms over his face and ward off most of the blows while yelling, “Get off! Get off!” But the blows kept coming, some of them pounding him in the chest and stomach, and one connecting with his nose, which started to bleed, and he thought he was going to pass out.

Suddenly, he felt the other boy’s body lifting off him, and he hovered in the terrifying lull, waiting to see the ratty red cowboy boots moving away on the cement. This did not occur. Instead, when he rolled over to get up, the first kick caught him in the ribs. Then another sent a fiery pain through his knee and another into his lower back. Then the kicks were coming from every direction, and the Lakota boy couldn’t tell which way to dodge the flurry of ferocious kicks. They seemed endless, and when they got closer to his shoulders and head, he began to scream.

That was when the elderly Lakota woman burst out the door of a nearby trailer house, tossing her shawl aside as she hurried down the wooden steps of the porch. She was across the yard and behind Cody Birch, her long fingers locking on the collar of his shirt as he was drawing his leg back. She dragged Birch, off-balance, across the sun-stiffened grass between two trailers until she reached a sandbox made from railroad ties, and flung him into it. Then she hurried over to help her grandson stand up and guided him over to her trailer, glancing one time with the glare of a hawk at Cody Birch before she quickly ushered her grandson inside and slammed the door.

Cody Birch lay in the hot, dirty sand which smelled of creosote and cat shit, sand caked at the corners of his eyes and his mouth full of sand. These were the taste and texture of his life—the bitter, dry grit of his mornings, afternoons, and nights; the coarse, nasty granules of time falling into the ever widening wound of his isolation. He sat up, peering down the street at the skyline of Box Elder, South Dakota, a combination prairie town and rural slum strung across the clay and alkali flats only a few miles east of Rapid City. It was a 1980s version of Steinbeck’s Hooverville, and in July it seemed to writhe and wither in the sun and scorching wind, its inhabitants eking out an existence amidst the trailer parks and shanties, the abandoned tractors and tumbledown garages and sheds, the stripped and rusting trucks, the crumbling, oxidized vans and cars, windshields shattered, pack rats ripping the remaining stuffing from seats. It was a place for the dispossessed descendants of the old gold seekers, the railroad builders, the hard-bitten cowhands and homesteaders, a boiling pot for drifters and oil field workers, and broken-bodied truckers and welders and mechanics. It had a few stores and bars and an elementary school, and it clung to the soil like the bitter blue sage that filled its yards.

This is where Cody Birch was born and had lived with his mother, an exotic dancer at the Buffalo Bill Bar in Rapid City, and her ever-changing string of boyfriends, some of whom ignored Cody totally, some of whom taught him to swear and to bare-knuckle box, some of whom answered his animalistic antics with backhanded slaps and kicks in the ribs. This is where Cody Birch went to first grade and couldn’t keep up with the other kids, couldn’t comprehend the alphabet, had no books at home, no crayons or pencils, no covers on his bed except for a U-Haul blanket, no toys but the grasshoppers and spiders he kept in jars he dug from the foul-smelling soil at the junkyard just south of Bitter Creek. This is where he was shunned by other children, who had nothing also but did have soap and a few clothes at home so that they felt justified in telling him that he smelled like a cow pie and that he was dumb and ugly and belonged in a pigpen.

He was neither dumb nor ugly, but he knew of no way to ward off abuse except with his hands and feet. So he became a fighter, a fierce and merciless attack dog his hecklers came to fear and eventually leave alone. But by then he had become inseparable from his own violence, and his rage only grew with his body so that, at eleven, he had the temperament of a wounded bear. His explosiveness caught his adversaries off guard, and before they knew what had happened, they were on the ground with blows raining down on them in the form of Cody Birch’s fists or in the savage staccato of his booted feet.

Birch’s barely-contained rage followed him through middle school in Gillette, Wyoming, and to tenth grade in Cheyenne, where he quit school at sixteen and, after lying about his age, went to work at a bentonite plant north of Belle Fourche, South Dakota. For the next ten years he was a rolling stone who punched and bit and kicked more people than he could remember and who got thrown into jail after jail until he finally changed weapons, stabbed a deputy sheriff in Thermopolis, and ended up in the state penitentiary. But for once in his life the stars lined up in his favor, the deputy pulled through surgery and lived so that Birch’s sentence got shortened, and he was eventually paroled. He drifted north and took a job mending fences on a farm east of Sheridan, Wyoming, just six months from the night he crossed paths with Scott Fife in the Sheridan County Jail.

Logan Fife almost didn’t recognize his son when he entered the empty cell and saw the prone figure lying on a cot in the center of the room. The lumpy face and puffed-shut eyes, blood coagulating at the corners, the lips swollen to twice their normal size, the flattened bridge of the nose, the blotchy purple cast to the face, and the bloat of the neck made Scott barely recognizable. In fact Logan’s mind took a sudden detour into thinking it wasn’t Scott.

When he came closer to the cot, the recognition stabbed him in the brain, and squeezed his heart to a frozen walnut in his chest. His throat seized with a sudden ache deeper than any choke-up he’d ever felt, and he was suddenly on his knees beside the cot, one hand clamped on the boy’s bruised forearm, as though to make the profoundly still body more real. A low, wailing moan rose in his chest and gained volume by the time it poured uncontrollably from his mouth. The law officers gathered in the booking room down the hall heard the sound through the hollow doors and the thinly plastered walls as it grew in resonance and pitch. They did not look at one another but fastened their eyes on oddly irrelevant objects—the Royal Crown calendar on the wall, their key rings, dead hornets on the windowsills, a pearl-handled letter opener on the desk—while the sound of Logan’s voice filled their ears.

Somewhere in the visceral rush of his agony, Logan, glancing at the senseless graffiti on the far wall, cried out to everyone and no one, “Who did this to my boy? Who did this to my boy?”

When he was given the answer by the sheriff in a dim, stuffy interrogation room twenty minutes later, he leaped from his chair, surging toward the door, and had to be wrestled to the floor by the sheriff and two deputies, all the while yelling, “I’ll kill the bastard. I’ll kill him!”

Only Jean Ann’s voice coaxing him back to earth once she had been summoned to the jail from the courthouse lobby was able to silence him, hold him in a nearly catatonic trance so that the officers could help him up and sit him in a chair. Deputy Jeff Redding, wanting to help Logan understand what had happened, was able to get Logan’s attention long enough to explain that, according to some prisoners who had witnessed the fight, Scott Fife had been minding his own business at the end of a bench in the rear of the communal cell when he happened to look up and catch the eye of a thirty-two-year-old drifter on the other side of the room. The drifter, a man named Cody Birch, already high on the drugs he had been trying to sell at a truck stop north of town, had been needling other prisoners for several hours, muttering about kicking someone’s ass, but got no takers to respond to his insults. So when Scott Fife caught his eye, Birch fixed on Scott immediately, leering across the cell as he spat out, “What’re you lookin’ at?” And Scott, still feeling his own liquor, had made the mistake of tossing out a comeback with, “I’m not sure what I’m lookin’ at,” and looked away.

From that point on, the witness said, it was only a matter of time before Cody Birch fidgeted his way to the other end of the cell, and only a matter of seconds before he had grabbed the front of Scott’s shirt and pulled him out to the center of the room. As one witness put it, it was like when you break a rack of billiard balls. Everyone cleared to the edges of the room while the older man stood glaring at the younger one, the majority of them following an unspoken jailhouse code.

Even after the scuffle began, only a few still looked on. Even after Scott, with what looked to be the skill of a trained wrestler, managed to get Birch in a headlock, and Birch had started growling and cursing, only the few took furtive glances. And when Birch broke Scott’s grip with a fierce blow to the stomach, which doubled Scott up on the floor, only one old man, too drunk and too weary to care what Birch might do to him later, looked on. It was he who told Jeff Redding about the worst beating he’d ever seen, about the kicking he thought would never end, how he thought at least some of the others would come forward and stop the madness, how two muscular bikers didn’t intervene until it was too late. Once they pulled Birch away, the old man added, Birch had turned and walked over to a chair he’d been sitting on earlier and which remained empty, and sat down and studied his boots as though he were stewing about the bloodstains on the toes.

Logan Fife’s urge to kill Cody Birch came flooding back, and his mind darted this way and that, seeking a way he might gain access to the room where Birch was being held. But the sound of Jean Ann’s voice drew him away from any thoughts of Cody Birch, and now it was his turn to hear his wife’s voice alternating between screams and sobs as she lay across her son’s body and cried, ”No, no, no . . .”

Logan snapped out of his trance then and convinced the officers to let him go to her. He lifted her away from the body and held her more closely than he’d ever held her—an embrace of one flesh, as in the one flesh they’d become in giving life to the silent boy lying on the cot. There was no speaking—no accusations, no rebukes, no pledges or resolutions. They could only stand there, so locked in the core of the present that the future collapsed and went black.

Jean Ann Fife gradually gained entrance to the future, taking solace from the love and companionship of her daughters and from her job at the homeless women’s center. She gave Logan all the support, affection, and encouragement she could, and so did his daughters, who did everything they could think of to console him, but he remained out of reach, rigid in his exile. For three years following Scott’s death, Logan tried all kinds of ways to reclaim his old place in the scheme of things and to feel something other than pain. He bore down on novice fire crews even beyond the grueling, two-week hiking ordeals he usually put them through. He jumped into fires with abandon and fought flames long after the rest of the crew had crawled exhausted into their tents. He hunted alone, tracking deer and elk with inordinate cunning. He ran naked through the forest and drank deer blood. He kayaked down Montana’s Yellowstone River with almost supernatural grace, knifed through every dangerous drop and boulder-strewn passage. He dared the river to kill him, outfoxing it at every turn.

His gambits seemed to bounce off the emptiness of it all. This infuriated him but only briefly; then the flame flicked out, and the ache returned.

It was the perfect shot, or what seemed like the perfect shot—the elk stone-still on a knoll at the center of the shooting lane, its antlers framed, as in a painting, by a border of evening shadows and set against a sun-guttering meadow that flowed back, back into a wall of dark trees. Logan Fife had knocked the arrow with intense concentration and stealth, gauging the forty-yard shot with machinelike precision. The elk filled the moment and the space it occupied with timeless poise and alertness as it stared down the ravine from which it expected the challenger to emerge, unaware that the bugling it had identified as a rival bull’s claim to its harem had been sounded by Logan Fife.

The stage Logan had been dreaming of for almost six years was set. He had dropped a large bull with a long distance shot during rifle season five years earlier, and the thrill of he and Scott tracking it down and carrying it out of the woods resonated in his memory. But this was even better. This elk was equal in size and had a rack of antlers that looked sure to break a state record.

To Logan’s great surprise, the arrow, at first lifting almost imperceptibly, rose significantly by the time it reached the elk, which, alerted by the thrum of the bowstring, had lurched at such an angle that the arrow pierced the thick fur of its neck. With the arrow protruding from both sides of its neck, the elk darted away as though nothing had happened.

Logan was stunned, his legs locked, as he stared at the empty shooting lane, then into the trees that had swallowed the elk. He came to his senses quickly, brushed off the demons already hounding him about a bad shot, knowing he had to track the elk down right away. But as he ran along the edge of the meadow, worry began to dog him. Surely the elk would bleed to death and drop to the ground shortly. Or it would try to hide, and he’d follow the trail of blood until he could catch up and put the elk out of its misery.

As he made his way through brambles and bushes, wound around tree trunks, leaping over rocks, the bow jouncing wildly and the arrows clacking in their quiver, he still could not believe that his shot had gone wrong. He had taken such a solid bead, the bow and arrow feeling a part of his body with a fullness and clarity from which everything else—past, present, and future—fell away. Yet the shot had gone awry, and the elk had transformed into something freakish, turning everything upside down.

He was starting to panic when he noticed blood spots on some leaves, then some drops on a boulder blocking the trail. He gathered his wits, called up his most reliable woodsman’s skills, and trusted his reading of signs. The signs came fewer and farther between, and the light, splintered by the trunks of pines, began to wane. If he didn’t find the elk soon, he’d have to return tomorrow, or the next day, or the day after that. And search and search and comb every inch of ground and backtrack and circle and leave markers.

Logan saw now from the darkening of the trees that he would be lost in the woods shortly if he didn’t return to his camp. He stopped at the edge of a ravine, eyes still sifting the slopes between trees, the openings between bushes, the distant beds of pine needles. He took out a handkerchief and tied it on a branch stub at a place he’d last seen blood, and he cut notches in a couple of fire-scarred trees as he made his way up the mountainside.

At dawn Logan returned to the spot he had shot the elk and worked deeper into the forest between two steep mountains, but found no sign of the elk, so he broke camp and went home. Two days later he drove back into the mountains but went beyond the turn-off to his original campsite and entered heavier timber. For the next four hours he hiked through nearly impenetrable undergrowth, waded streams, and climbed rockslides until his fingers were bleeding.

By late afternoon Logan was approaching delirium and was seeing the elk with the arrow in its neck feinting at him and dodging behind trees. He slowed his pace and eased the churning of his mind. It came to him that he had unaccountably spaced off his own recollections of stories he’d heard from other hunters about seeing deer and elk running through the woods with arrows protruding from shoulders and rib cages. And stories he’d been told about people finding, while dressing out deer, arrowheads or bullet slugs embedded in crusted-over pockets of flesh and hide. The chances were equally good, then, that the elk might still be alive and would survive the wound. It might already have rejoined its harem and was leading them to higher ground, the ends of the arrow glancing off branches or snagging on leaves, only to tear loose and go wherever the elk went. Or the arrow had broken off on one or both sides, and the elk was then able to maneuver as before, stronger in some bizarre way for taking the arrow into itself, into its wildness, and struggling on. In the end, Logan knew now that he had to stop searching and let the elk go. It was OK to let it go; there was nothing more he could do.

He cut through a patch of clover and sat down on the stump of a tree that had been toppled by lightning. The forest in front of him seemed a leering maze of color and shadow. With its intricately woven veneer, it hid everything that needed hiding; it had reclaimed the elk with brute defiance. There was no way to right what had happened to the elk. It wasn’t even a matter of right and wrong. It just happened in hunting, and he couldn’t change it any more than he could change what had happened to Scott. You simply could not blame yourself for the movement of the world. You were in the world, whether or not you wanted to be in it, but you were not in charge of it. He realized then that the blaming had to stop. Blame and shame were killing him, and he wanted, in the worst way, to live.

Tugging his cap in place and adjusting the straps on his backpack, Logan rose from the stump and looked at a stand of trees near the rim of the ravine he would follow in returning to his truck. He didn’t see the woodpecker at first, but then caught sight of it flying from one tree to another, securing its hold on the trunk with tiny claws, testing the bark with its power-drill beak, seeking a feast in the primal resistance of wood.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop