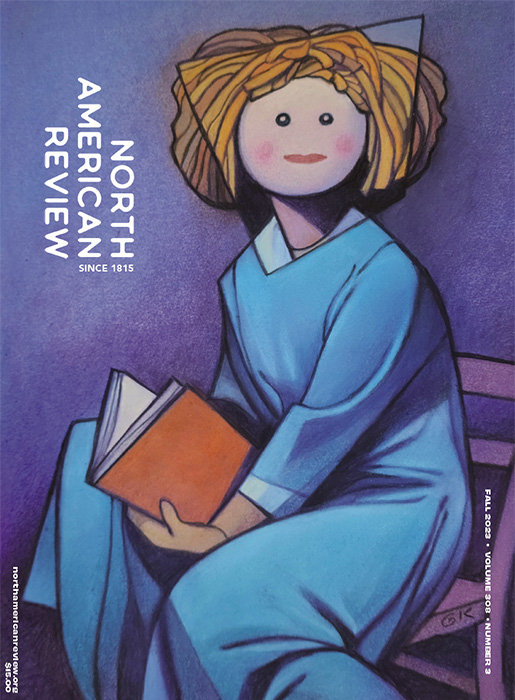

308.3 Fall 2023

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

FROM THE EDITORS

Greta Gerwig’s summer blockbuster Barbie opens with a humorous cinematic homage to the Dawn of Man sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. Instead of apes, a gathering of drab-clad young girls plays on a bleak outcropping of rocks, pushing their old-fashioned baby carriages and feeding their dolls like the dutiful mothers they’re meant to become one day. Instead of the black monolith, a colossus appears: Barbie, wearing a striped bathing suit worthy of a ’50s pin-up calendar, white-framed sunglasses, gold hoop earrings, bright red lipstick, and high heels snug on her high-arch feet. The girls gaze up in wonder at this alluring figure of modern femininity. She smiles big, lowers her sunglasses, and winks (at the girls, at history, at us through the camera). And finally, the turn: instead of an ape smashing the bones of a tapir and thereby becoming something other than he was before, a girl smashes her old baby dolls, thereby becoming something other than she was before. Slo-mo shards of plastic fly. Cue the Wagner.

In this framing, Barbie represents a cultural event horizon, the leap of imagination that, once taken, can never be taken back. We cannot unsee her beauty. We are forever changed. But Barbie is not Prometheus so much as fire itself, an idea gifted to us from Olympus. Just as Kubrick’s apes will inevitably wield tools, invent language, drop bombs, and launch spaceships, little girls everywhere are now able to imagine a life beyond their future maternity, for better and for worse, allowed to become the agents of their own desires—doctor, president, construction worker, astronaut—not to mention the feminized (read: sexualized) objects of masculine desire. Be a doll, says the doll, would ya?

To paraphrase Flaubert, “Barbie, c’est moi.”

“The doll is a sardonic creature,” writes Muriel Harris in the pages of the North American Review in 1920, forty years before the Dawn of Barbie, whose wink must be read with just a hint of mischief. As an object given to children, the doll is ancient, having been around for thousands of years, but “she remains unchanged and unchanging, throughout history, nursing our delusions, giving us away without scruple, a silent witness to our emotions and our needs, to the futility of all our efforts to present ourselves as other than we are.” With whatever material is at hand—rag, bone, wood, wax—we have always fashioned little versions of ourselves to play with. Diversion, dream, desire: doll.

The doll-face overlay in Gary Kelley’s “Projection (Women Treated as Dolls),” which appears on the cover of this issue, captures one important facet of the doll’s sardonic nature. The image is uncanny not because we are confused or afraid of an inanimate object coming to life but because we can so easily imagine the opposite: becoming dolls ourselves, losing our minds, our agency, our very existence. In fact, the Barbie movie becomes a kind of doll, too, produced as a bright and energetic soundstage musical comedy harkening to the time of the Barbie doll’s mid-century origin (à la Busby Berkeley and Vincente Minelli). It’s an indulgent fantasia, pure performance, every moment vividly expressed on the surface. Even so, Barbie doesn’t wear a mask—it’s mask all the way down. She has no interiority, until, of course, she does, at which point she ceases to be a doll, like Pinocchio and the Velveteen Rabbit before her. Our hero must travel to the Real World to make Barbie Land perfect again, but she is, like all heroes, changed by undergoing the ordeal. Spoiler: she becomes flawed, mortal, embodied, imperfect, haunted by anxiety and thoughts of death. In other words, human. Us. Barbie, c’est moi.

Not all of the writing in this issue of NAR addresses dolls explicitly, of course, but the spark (and promise) of Barbie’s flawed, mortal, embodied, imperfect humanity imbue every page. Serena Algappan’s essay “Untranslatables,” selected by Ira Sukrungruang as the winner of this year’s Terry Tempest Williams Creative Nonfiction Prize, articulates with linguistic subtlety our human need for connection and the frustrating inevitability of disconnection. “What makes us think certain phrases cannot be carried across different languages?” she asks. “Preference? Linguistic hegemony? A failure of imagination?” Algappan traces the challenges of authentic communication and the problematic dynamics of power that accompany translation, returning again and again to the fundamental relationship between self and other, I and thou.

Like dolls, much of the prose in these pages, whether it’s written in a speculative mode or not, draws attention to what is and is not real: the stark dystopian world of Lyndon Nicholas’s “Moko Jumbie,” the eternal (paternal) return in Alexandra Wuest’s “The Fathers,” the uncertainty about a potential surrogacy in Kate Cayley’s “Expectation.” In their essay “Womb, Tomb, Table,” L Favicchia tells part of the history of the Resusci Annie doll, Xin Zhui (the best-preserved human in the world), and other bodies treated as doll-like objects. The poems, too, ask fierce ontological questions. Helena Feder’s “What It’s Like to Be a Bat” picks up Thomas Nagel’s classic thought experiment; Alyse Knorr’s “An Excruciating List of Uncertainties” is given the last poignant word that we all, however uncertainly, must live with; and Ed Coletti’s “It’s Easy” reminds us of the great Honus Wagner’s simple but hopeful tautological truth of existence: “There ain’t much to being a ballplayer—if you’re a ballplayer.” ⬤