Tilling the Fields of the Unspeakable

The root of collaboration is both direct and discerning. From 1830, to collaborate is the “act of working together,” a “united labor,” especially in literature or scientific study. The word gained ground in the French language as a noun of action born of the Latin collaborare, “to work with,” and from the late fourteenth century, “to work hard; take pains, strive, endeavor; produce by toil; to suffer, be afflicted, in distress, or difficulty.” Finally, collaboration also comes to us from the modern French, Spanish, and Portuguese, meaning “to till the soil,” or “to plow."

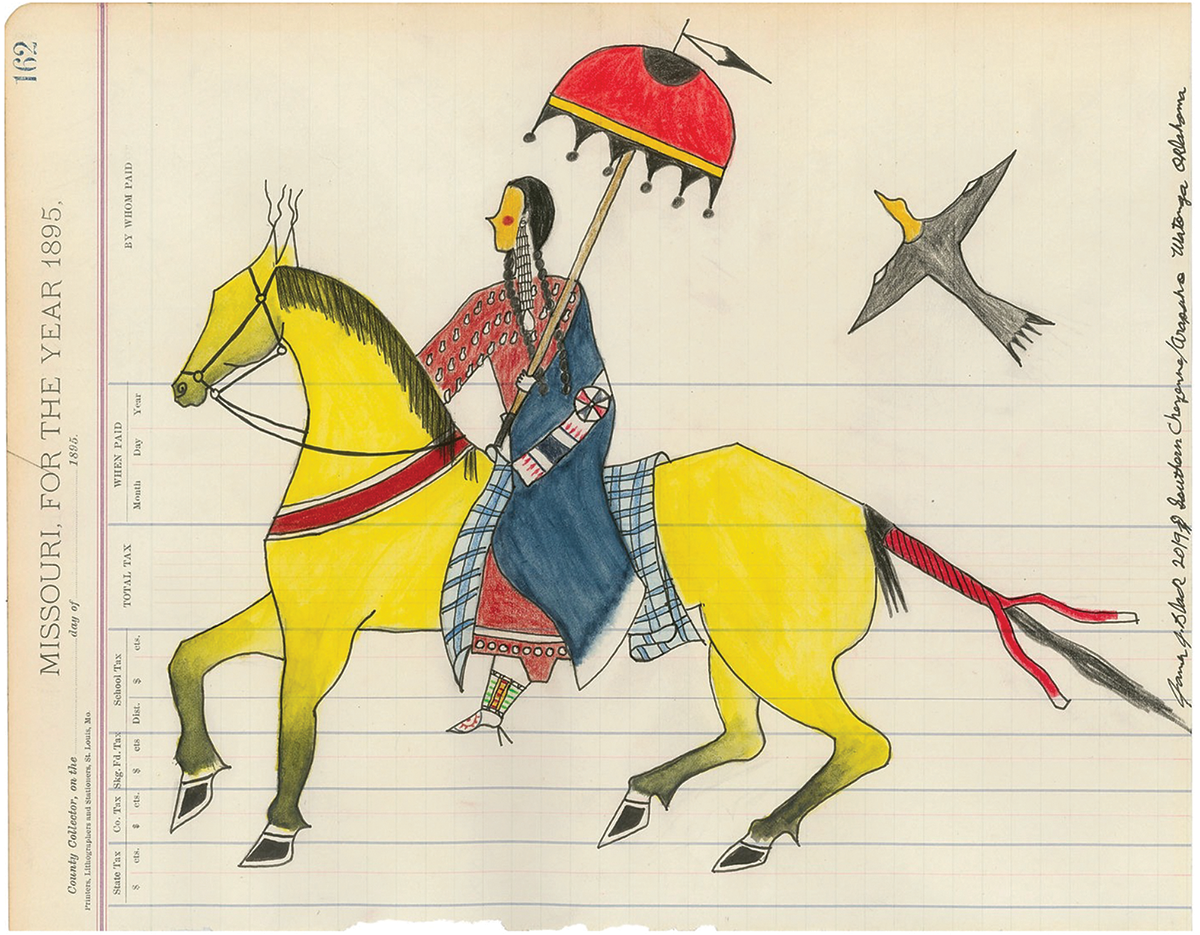

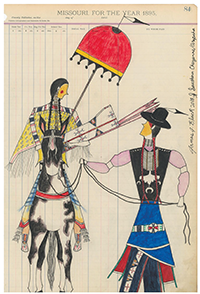

The collaboration I’ve been honored to be a part of in North American Review, a dual work integrating poetry and ledger art, represents a uniquely restorative form of tilling the soil. The poetry and ledger art found in the two poems and two images from James Black and me featured in NAR are part of a larger book-length project that speaks to the brotherhood shared by a Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho ledger artist and a Czech American poet. By composing unified art, we hope to open a doorway into the powerful love among brothers worldwide. Honoring compassion while refusing to look away from the individual and collective capacity for great violence, these images and poems seek to engage the genocidal weight of history alongside the crisis of fascism and nuclear warhead proliferation accelerating globally in the present day. In offering peace and well-being against the imminent threat of annihilation, we entreat the human community to hold the beloved’s face, to speak love not hate, choosing to live not against but toward the restorative essence that foretells the reconciliation of people and nations.

In working with NAR editor Jeremy Schraffenberger an idea came in which I recognized how significant it is that James Black’s images have come to appear in NAR. The magazine was founded in 1815, and has been an integral voice in forming the long foundation of American literary concerns. From the nineteenth century, writers of great renown appeared in NAR’s pages such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, John Adams, and Edith Wharton; and twentieth-century writers like William Carlos Williams, John Steinbeck, Thomas Wolfe, William Saroyan, and Flannery O’Connor also made important contributions; and finally, contemporary artists such as Raymond Carver, Margaret Atwood, and Joyce Carol Oates have continued the great depth and breadth of NAR. For more than two hundred years, NAR has shaped culture, and over time has been shaped and reshaped and transformed into the beauty of now.

Notably, for the first hundred years of NAR, a genocidal pall fell over the Americas in the form of what is often termed the Native American holocaust—conservative estimates placing death tolls at twenty to forty million. As those who came before us, James and I believe artistic embodiment is needed to examine the United States’ historical and present wounds exerting immoral hungers not only domestically but internationally. Jeremy noted how one of the North American Review’s character words is the word restorative. “We often think about our relationship to time and place,” he said, “not just the past but today as we are immersed in the constant flow of history.”

When leaning into the nature of what it means to be restorative, the past informs the present and leads to the future. Consider James and his work. He is a sun dance priest, an artist, and a descendent of the Cheyenne prisoners of war, Cohoe and Making Medicine, who were held at the old Spanish battlement, Fort Marion, in St. Augustine, Florida from 1875-1878. During the decades when people of Native Nations en masse were displaced, mutilated, and killed, America, like all nations, contained hope for some, trauma for others. James’ forebears suffered under the dominant, militaristic, genocidal practices of the United States, and like the Peace Chief Black Kettle, many suffered to the point of death.

In this collaboration, James and I seek to honor restoration, to honor life giving possibilities such as dance instead of war, and to draw from the brotherly love we’ve been humbled to experience throughout our lives.

Now consider the North American Review as a form of lightning rod to the notion of ultimate irony, seeking to frame restorative practice by naming the nation’s shadow in the past and present. In fact, Harriet Beecher Stowe, mentioned above, worked as an educator with the Cheyenne prisoners at Fort Marion. I consider this type of naming vital for the healthy eating of one’s own humiliation which occurs in all legitimate restorative justice, atonement, and forgiveness processes, a journey engaged by James today as a Cheyenne sun dance priest and ledger artist. The sun dance and the year preceding it for sun dance pledges involves restorative purity, discipline, and the great endurance involved in bringing new life to the people.

Some time ago, James and I embarked on a collaboration called Brother My Brother, an exploration of toxic human relations set against the restorative properties of love. The poems and visual art appearing in NAR and in the larger collection consider how brothers love each other, how they destroy each other, and how they are sometimes given the grace of reconciling with one another. We hope to honor our grandmothers, mothers, aunties, sisters, and daughters in how they have led us in this path. In light of pervasive detachment, alienation, and despair, when considering the weight of interpersonal fracture alongside the current rise in fascism and thermonuclear warhead proliferation, we envision a return to love and communal kindness.

Brother My Brother evokes the immanent dangers of quantum science and the reality of love as a unified field below all. We indict the desolations wrought by toxic masculinity, and we engage the long held unity found in brotherhood that chooses vulnerability and speaks against the myth of regeneration through violence. Magnifying ecological and interpersonal global unrest we consider forgiveness in the wake of unconditional harm, the art and science of forgiveness, restorative justice, and ultimately shared intimacy as bridges of healing between people and nations.

What brought James and me together is historical and personal. The descendent of Czech immigrants, I grew up on the Northern Cheyenne reservation in southeast Montana, and James grew up on the Southern Cheyenne reservation in northwest Oklahoma. When I consider our work together I think of two touchstones: first, my grandmother Katherine’s voice as she spoke and I listened; and second, a Cheyenne gift given to my father by the Cleveland Highwalker family. On the plains of Eastern Montana my Czech American grandmother was a postmaster, and a force of life. Sixty miles outside Miles City in a town called Cohagen, an outpost of eight people, her post office was a beacon of friendship and good will. Her mother had the surname Lev, meaning “lion.” Little Dry Creek ran in the draw below the house. Water snakes, bolts of green and yellow, skated the water’s surface. Summers with my grandmother and grandfather, we worked cattle, stacked hay, and cleaned rodeo grounds. I remember the dark wooden mailboxes in her office, her easy way with women and men and their families, and her embrace of horse culture. She was Czech, my grandfather was German. They married in New York City during World War II just after Germany had invaded Czechoslovakia and commenced genocide of the Czech people. They moved west to Montana and square-danced through a fifty-year marriage. In fact she had two knee replacements in her seventies to keep dancing! A rhyme she taught me as a boy stays with me. In Czech, the words are melodic: Beruško, kam poletíš, do peklíčka nebo do nebíčka. In English, they are grim:

Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home,

Your house is on fire,

Your children shall burn.

Centuries ago the rhyme was sung by farmers when burning their fields after harvest, urging the ladybird, or ladybug, to fly home, where only one of her children remained hidden, unburned, under a stone. The ladybug, a sacred symbol of safety from pestilence, beckoned a blessing—the hope that one’s life work, and thus one’s family and children, would be protected. My grandmother soothed me with song and met me with the truth that the world is not always safe. I still hear her voice calling me “miláčku” the Czech word for “darling.”

On the Northern Cheyenne reservation in southeast Montana, my dad’s closest friend was Cleveland Highwalker. “Best person I’ve ever known,” he said. They played basketball, hunted, and fished. Cleveland was beloved of the Cheyenne, a young man adored for his youthful exuberance and athletic heroism. I still picture Cleveland long-legged with a tall broad shoulder, his open face, and kind eyes. The soft sweet swish of his jump shot. My dad tells of a time he and Cleveland made the trek to Cleveland’s grandmother’s house, a remote distance over fields of snow. My dad brought her two deer, a gopher, and a magpie. “Good trade,” she said in Cheyenne, “very good,” as she pushed her fist forward in a sideways motion, affirming the trade. She traced my dad and mom’s footprints on leather she later chewed to soften. That leather became two pair of intricately beaded moccasins. My father loved alcohol, too much he’d say now, as did his father before him, while Cleveland hated alcohol and didn’t drink. Cleveland had a good job with Montana Power. He was big-hearted, smart, on the rise. His future held such promise. My father and Cleveland shared a brotherhood of sports and friendship. But before Cleveland was thirty he took his own life.

In this collaboration, James and I seek to honor restoration, to honor life giving possibilities such as dance instead of war, and to draw from the brotherly love we’ve been humbled to experience throughout our lives. In suffering, we remember the past and hold it close in order to prevent a repetitively harmful future. James is a descendent of those massacred at Sand Creek, the Washita River, Fort Robinson, and locations throughout the American West. I am of the bloodline of those massacred at Lidice, Ležáky, Lejčkov and locations throughout the Czech lands. By moving as artists to form a brotherhood of hope, we see artistic collaboration as an antidote to fear. Both the human and the more than human community gives the nature of collaboration greater life, and helps us draw near to one another, gaining hope as we gather in solidarity with those who suffer worldwide. We envision peace and wellbeing, as we sing with sisters and brothers on the margins everywhere, asking Meheo, the Wise One Above, asking God the Divine who dwells in thick darkness, for the opportunity to embrace friends and enemies toward restorative peace. We are reminded, being from both the high plains and from mountain country, when one sees blackbirds rise from a winter field or hears the quiet breathing of horses, we give witness to the beauty of wilderness and the beauty of the human heart.

Restoration, a character word for the North American Review, and a word of soul for people, families, and nations, unites us with other words that represent character: listening, gentleness, generosity, authenticity, and a hard won sense of communion.

For James and me, our collaboration has focused on the genocide that occurred at Sand Creek against the Cheyenne, and on the genocide that occurred in Lidice outside Prague against the Czechs, embedding these narratives in an interrogation of violence that ranges from person to person and culture to culture to the violence signaled by nuclear warhead proliferation worldwide.

During the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 in the Colorado Territory, US military mutilated and desecrated the bodies of Cheyenne and Arapaho men, women, and children. The commander who directed the attack, Colonel John Chivington, a Methodist minister, openly referred to Cheyenne and Arapaho adults and children as “lice” and devoted himself to “kill them all.” At the Apollo Theater in Denver, Chivington and his men put Cheyenne body parts on display, including fetuses, genitalia, and the pubic scalps of women.

During World War II, in the razing of Lidice, a small town outside Prague, the brutality of the Nazi state was revealed. All men were killed. Women were shipped to concentration camps. Eighty-two children were sent by train to Lodz. The youngest child was one year and six days old, the oldest boys were under fifteen, the oldest girls under sixteen. In early June the children were taken to a castle and told to undress. They were placed into the closed bed of a truck modified to exterminate human bodies and killed by exhaust in eight minutes. In Russian the trucks were called dushegubka: soul killers.

Feminist activist bell hooks said America is bound by a system she referred to as a calcified patriarchal supremacy from which Americans find it impossible to escape. Erasure and dominant culture toxicity are the result, breeding homicidal and suicidal realities. She also stated the answer to such a demeaning and degrading system can only be love. Through a collaboration of art meant to suffer with and bear with others under our collective suffering, James and I hope to present a home country of care and lovingkindness in the face of disunity, fear, and abandonment.

In Cheyenne sun dance or new life ceremonies in southeast Montana and central Oklahoma, restoration is an outflow of people in community. People gather to support those who dance in honor of new life. People bear the dancers up in heart and spirit, and carry them physically when the dance is complete. In Czech sites of post war healing there is an echo. In what is now called the Garden of Peace and Friendship in New Lidice, a world reconciliation site outside Prague, the children of Germany were asked to join the children of Czechoslovakia post war to plant a garden of a hundred thousand roses sent from fifty-one countries in solidarity and recognition of new life. Face to face encounters such as this, both in the US and Europe, ground our experience of restorative brotherhood post genocide.

People are largely unfamiliar with forgiveness and atonement in the wake of genocide. The research on reconciliation in such contexts points to forgiveness within atonement as singularly crucial in healing people and nations. Overwhelmingly, history reveals men rather than women, generate wars. With James, I ask what are we actually doing to teach brotherhood and peace in the nuclear age? The proliferation of thermonuclear warheads creates dire urgency. A genocidal tendency at work in the world is ancient, and requires a reversal that will restore people to one another and hold us back from humanity’s most base appetites.

The Czech nursery rhyme my grandmother sang to me foretold a world beset by a crucible of fire. In calling me miláčku, in calling me darling, she set me free to explore this world in all its friendship, brotherhood, and ferocity, in its vast desolations as well as the immanent grace of a consoling and enduring love. In the traditional way, James’ family taught him the necessity and restorative beauty of the sun dance in bringing new life to the people. Me and my family live in the shadow of Lidice. James and his family live in the shadow of Sand Creek. As families, we hold hope for our children and for each other’s children. To a world caught in the grip of atrocity, a collaboration containing the hope of restoration can give gifts to the beloved. Restoration, a character word for the North American Review, and a word of soul for people, families, and nations, unites us with other words that represent character: listening, gentleness, generosity, authenticity, and a hard won sense of communion. With the images and poems in NAR, and in the larger collaboration Brother My Brother, James and I are grateful for the fortitude of those who came before us seeking peace and unified commitments. We hope to honor their legacy, and honor brotherhood as a revolution of love that expresses our deepest held feelings in the face of the unspeakable.

Recommended

Crossing Paths

I Have Only Dreamed You Dead, For Now.

Encounter