Thrice Told?: Echos of Hawthorne’s Twice Told Tales in Ted Morrissey’s Novels

We recognize the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne as one of the finest and earliest examples of American literature. He transcends genres—mystery, horror, fantasy, allegory—while using their tropes. His use of allegory is especially noteworthy. While allegory assigns a single meaning to a dark wood, a garden path, or a veil, Hawthorne shatters such unified intention, allotting each jagged shard with its own significance. Hawthorne’s Young Goodman Brown meets the devil in a dark wood, where he is forced to contemplate the irony of his own name as well as the reputation of his wife Faith and the rectitude of the upstanding authorities of his community. Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne embroiders the letter A with such able craftsmanship that we might come to consider her an artist rather than an adulteress. Like Hawthorne, Morrissey plays with the conventions of allegory to create ambiguous meanings.

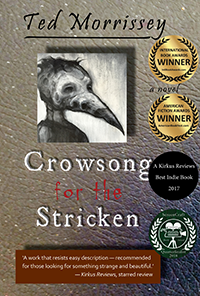

I first heard Ted Morrissey read at the Albany Park Library in Chicago this past September when he presented a chapter from The Strophes of Job (written in 2024, set in 1907), which had just come out in paperback. Intrigued by his reading, at the end of the event, I picked up his earlier companion novel Crowsong for the Stricken (written in 2017, set in the 1950s) to read at home along with The Strophes. Within a few pages into Crowsong, I found myself comparing Morrissey’s style to Hawthorne’s. Like Hawthorne, Morrissey presents fantastical elements ambiguously, in such a way that realistic or psychological explanations cannot unequivocally be ruled out. Indeed, we, as modern readers, unequivocally rule them in but we might spend days wondering exactly how to do it, for traces of allegory in the 21st century writing, or even in the 20th century setting, are a bit unsettling. Pre-teens dressed in shorts enter the forbidden woods, not Puritans dressed in breeches. Some of the religious rituals Morrissey introduces might stem from the Puritans, while others seem pagan or are remnants from the Shawnee tribe who once inhabited the land surrounding the town, and still others bear the influence of Morrissey’s own Roman Catholic background. He doesn’t formulate as coherent a theology as Hawthorne does, but his interest in evil and spirituality is as intense. Morrissey told me, “I take some of my writing techniques from abstract art, slapping paint on a canvas in interesting ways. . . I have intentions, but I know they will interact with each reader’s experiences and point of view. I embrace Samuel Beckett’s technique of ‘vaguening’: provide a few details and let each reader fill in the rest.”

One of my favorite stories or chapters in Crowsong involves two pre-teen girls—Frankie and Rebecca—who spend a long, boring summer in each other’s company. Frankie is new to town, and Rebecca hopes to impress her by acquainting her with some of the town’s mythology: Hollis Woods, for example (so named because the five Hollis children many years before had vanished as they entered the woods one by one and still haunt it), and Lucifer’s den (a cave deep within Hollis Woods where the devil dwells “on taloned feet while his hands [are] hooked claws” ever ready to “snatch your soul”). Emboldened by her own storytelling, Rebecca promises to take Frankie to the cave, but then afraid, she regrets her promise. What is revealed and what is concealed on their visit goes deeper than a slick rhetorical trick, but rather parallels what we might experience on a spiritual pilgrimage. The chapter ends with the girls “clasping hands,” and committed to a “secret”: “They alone would smell the cave’s primitive scent.”

"I embrace Samuel Beckett’s technique of ‘vaguening’: provide a few details and let each reader fill in the rest.”

While Crowsong for the Stricken might arguably be called a series of short stories rather than what Morrissey insists is a “prismatic” novel (one in which you can read the chapters in any order), The Strophes of Job is unified by the weather creating a more traditional novel in form, one with an overarching conflict: the need to survive a relentless snowstorm, a storm especially challenging for midwife Emma Houndstooth, who must tend to two different women, each of whom is about to give a breech birth. She is haunted by ghost children, babies who died as she tried to bring them into the world. She carries a lantern as she goes about her tasks. In an allegory, the lantern might symbolize enlightenment, but not here. Later in the novel, Robert Frye, husband of one of the pregnant women, stumbles on a discarded lantern buried in the snow: “Robert kicked the worthless lantern off the path—it could remain dark forever.” The dark whiteness of the blowing snow, reminiscent of Melville’s “the whiteness of the whale,” creates existential horror (not purity, not innocence) as the horizon blends with the ground, blurring the intentions of those who must set out in the storm.