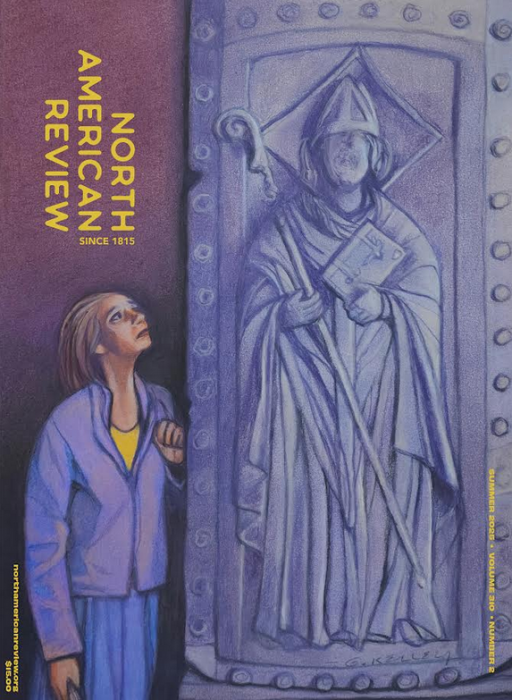

310.2 Summer 2025

Buy this Issue

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

FROM THE EDITORS

The tribunal is empowered to impose prison sentences from a few months to a life term. Another of these laws provided for the deportation to the penal islands of those who might be denounced as enemies of the Fascist règime.

Francesco Fausto Nitti,

“Prisoners of Mussolini” (1930)

On the morning of December 2, 1926, Francesco Fausto Nitti was leaving for work when three police agents in plain clothes burst into his home, escorted him to the station, and informed him without explanation that he was going to prison. He hadn’t been charged with any crime but was told by the assistant commissioner, “Your imprisonment is an administrative measure.” Such is life for anti-fascists under fascist regimes: administrative measures in lieu of due process, executive orders trumping habeas corpus. Italy’s “Exceptional Laws for the Defense of the Nation” of 1926 were a series of decrees by Mussolini to outlaw oppositional political parties—including all anti-fascist activities—and establish military tribunals that operated beyond judicial reach. This simultaneous expansion and consolidation of power was a response to the four assasination attempts against Mussolini in a one-year period. He enjoyed popular support after one of the attempts, when his nose was grazed by a bullet while walking through the crowd in the Piazza del Campidoglio. Pictures of Il Duce shortly afterward show him wearing a conspicuously large white bandage on his face.

What do they say about history rhyming?

In the February and March 1930 issues of the North American Review, Nitti recounts his experiences of mistreatment as one among thousands of political prisoners in the largest (yet “hopelessly overcrowded”) prison in Rome. He was held there among actual criminals, including violent gangsters from the Sicilian Mafia, before being deported to the penal islands of Lampedus and then finally Lipari, where he spent more than two miserable years. Then one night under cover of darkness, he escaped with two other dissidents in a boat helmed by anti-fascist comrades. This harrowing story formed the basis of Nitti’s 1930 book Escape: The Personal Narrative of a Political Prisoner who was Rescued from Lipari, the Fascist “Devil’s Island.” He continued his political activism in occupied France, where the Nazis eventually captured him as a prisoner of war in 1944. On the way to Dachau, however, he escaped once again, this time by removing the train car’s floorboards and lowering himself onto the tracks as the train rumbled northeast, inexorably, toward Germany.

Why have we been thinking about fascism lately? Oh, no reason. Why do you ask? Why would we possibly be interested in governments who target individuals expressing unpopular political opinions? Why should we care about people being arrested or deported or tortured or killed without due process in the name of national defense? I mean, we’re an arts publication, people. It’s impossible to imagine that the meager federal grants set aside for the arts and humanities could be summarily snatched from organizations who’ve already been promised funding. And besides, we’re housed at a public university. It’s not as though we live in a country where higher education is under attack, where the state itself is reaching its hands into our curriculum to control it, to rewrite and whitewash history, to claim that we have complete academic freedom as long as we don’t say DEI or critical race theory or systemic racism or trans rights or any number of other un-American ideas. Why would we say such things in a free country like ours?

The North American Review may be going out on a limb here when we proclaim to be staunchly anti-fascist. It didn’t used to feel dangerous to say so, but there you go. As such, we embrace the principle behind the sticker on Woody Guthrie’s guitar: art is a machine that kills fascism. That’s why they’re scared of us. They know that what artists wield is powerful. The stories, essays, poems, and visual art in the issue you hold in your hands is testament to that fact, starting with Corina Bardoff’s “Barbara Blue,” selected as the winner of the 2025 Kurt Vonnegut Speculative Fiction Prize by Kevin Brockmeier, who describes it as a story in dialogue with fairy tales that “offers all the classical satisfactions but that still, somehow, consistently surprises you with its narrative maneuvers and its wily sensibility, sending out sparks and pinwheels of the most extraordinarily vibrant prose.” Three other Vonnegut finalists also crackle with speculative energy: Madeline Furlong’s near future dystopia “Dream Home,” Evan Greif’s cyberpunk thriller “TOF.exe,” and Carolyn Mikulencak’s haunted allegory “Agony Acres.”

Many of the essays in this issue feature strong women raising a fist of resistance, from Aimee Maddalena’s “Mary Hunter Austin and Songs of Home” to Rowena Leong Singer’s grandmother in “Ghost from Chickens Past,” to Amy Monticello in her fierce and important “A Woman’s Prime.” A folio of poems curated by New Zealand Poet Laureate Chris Tse may be “a point of departure,” but we’re sure that the work of Hinemoana Baker, essa may ranapiri, Jiaqiao Liu, Liz Breslin, and Michael Steven will be a place you’ll return to, as one returns home to find it different, new, a little strange, but astonishingly beautiful.

Nitti himself finally returned home to his native Italy in 1946. He remained active in the Italian resistance for the rest of his life, editing the antifascist magazine Patria Indipendente. You may be surprised to learn that it’s still being published today. And why is it still being published today? Because it is always necessary to oppose fascism. ⬤