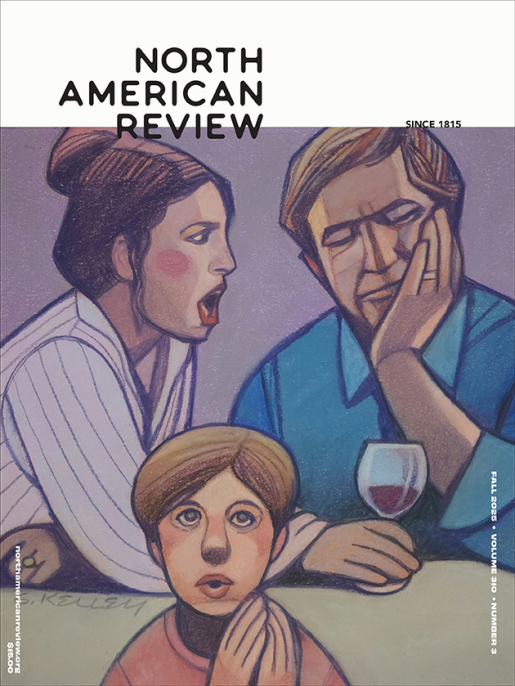

310.3 Fall 2025

Buy this Issue

Never miss

a thing.

Subscribe

today.

We publish all

forms of creativity.

We like stories that start quickly

and have a strong narrative.

We appreciate when an essay

moves beyond the personal to

tell us something new about

the world.

Subscribe

FROM THE EDITORS

The poor harried editor hardly knows what to write for his introduction to the latest issue of the North American Review. Too much is happening in the world around him. He could comment on any number of alarming developments initiated by the agenda of a recently elected, ultra-conservative president’s administration. Deregulation, tax cuts, funding for government programs slashed. It’s not September 2025. It’s September 1981, and editor Robley Wilson gloomily notes “the size of the defense and welfare budgets, the future of the labor movement, and the general prospect of survival.” Forty-four years later, another former entertainer occupies the office, and yet again we’re saturated with a never-ending stream of one story after the other.

What will the audience tune in to watch tonight? Gaza, Ukraine, tariffs, inflation? USAID, CDC, BLS? How about the politicization of the civil service and judiciary, armed military officers policing the streets of American cities, and masked agents apprehending law-abiding residents? Inhumane detention centers? Deportation without due process? There’s always the (dead) sex trafficker, not to mention the (living) sex trafficker who was conspicuously reinterviewed and promptly relocated to a cushy minimum-security joint.

The zone, as they say, has been flooded, and it’s all we can do to keep our heads above water. That seems to be the point: drown us in a sea of chaos and distraction. More troubling still: institutions with the money and power to stand up to the inundation (law firms, media companies, universities) choose instead to take a knee. (One is tempted to say “bend the knee.”) For the already-wealthy, immediate self-interest trumps the long-term viability of democracy, to say nothing of the “general prospect of survival.”

With so many stories to focus on back in September 1981, why did Robley Wilson choose to reprint Andrew Carnegie’s famous essay “Wealth” (first published in our pages in 1889 and later known as “The Gospel of Wealth”)? And why do we return to it today? It might have something to do with emoluments, personal enrichment, and crypto grift. It might have something to do with the specter of a creeping techno-authoritarian broligarchy.

Carnegie argues that the wealthy are morally obligated to spend their great fortunes on behalf of the public and for the common good rather than hoarding it and then leaving it to their heirs. “We reprint it as part of our occasional historical self-consciousness,” explained Robley, “and because the philosophy expressed by Mr. Carnegie seems not only appropriate to the American present, but even slightly more enlightened than today’s spokesmen might have it.” Admittedly, our “historical self-consciousness” of late tends to be more than occasional. In 1981, wealth was supposed to trickle down. Today, it defies gravity. A trillion dollars for the poor becomes a trillion dollars for the wealthy. Voilà! It’s not magic. It’s math. Just ask the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (while it still exists).

Carnegie was an immigrant, arriving as a child in the United States in 1848 from Scotland, the poor son of an out-of-work weaver. He wasn’t naturalized as a US citizen until 1885. (In another era, would he have been detained by ICE and deported?) In his humble beginnings, before becoming the titan of the steel industry, he worked as a bobbin boy in a textile mill and a messenger boy in a telegraph office. Yada yada yada, hard work, rags to riches, he became the wealthiest man in the world. Carnegie, Rockefeller, Vanderbilt. Today you’d say Musk, Zuckerberg, Bezos.

Because we could use more of Carnegie’s forward-looking philanthropy today, it is in that spirit that we redistribute a wealth of stories, poems, essays, and artwork, beginning with Nancy Geyer’s contemplative “Playgrounds & Kurosawa’s Ikiru,” selected as the winner of the Terry Tempest Williams Creative Nonfiction Prize by Robin Hemley, who calls the essay “quietly powerful and confident in its exploration of its concerns and obsessions with mortality, legacies, and connections (and disconnections) between the old and the young.” He admires that “the writer speculates on the quiet heroism of seemingly small gestures, the ways in which we seek continuity with the past through memory and location, and what it means to be both a part of and separate from a community.” We offer our congratulations to Nancy, and a hearty welcome to Robin as our newly minted contributing editor!

Also for the public good, we present Frances Cannon’s “Undiscovered Country: A Queer, Unearthly Adventure,” excerpted from her graphic biography of Isobel Wylie Hutchison. Hutchison was born in 1889, the same year “Wealth” appeared, about ten miles from where Carnegie himself was born, just across the Firth of Forth outside of Edinburgh. Frances narrates and illustrates Hutchison’s equally fascinating (if less well known) story as a writer, painter, and world traveler gathering botanical specimens. Filling in the blanks of Hutchison’s shrouded private life, Frances speculates on her sexuality and gender. We look forward to her visiting our campus in October for our fourth annual National Coming Out Day reading.

Carnegie was a frequent contributor to the NAR, writing more than twenty pieces for the magazine between 1886 and 1911. In 1906 he revisited “The Gospel of Wealth,” updating it for the twentieth century. “Where wealth accrues honorably,” he reminds us, “the people are always silent partners.” Wealth inequality, therefore, is inherently unjust. The wealthiest man in the world foresaw a hopeful day in the future when we might all accept this plain and simple truth as gospel. ⬤