Crossing Paths

We’re headed south from St. Louis on I-55 toward a little town called Perryville, population 8,500, more specifically, to a farm outside that town owned by my sister-in-law’s parents, Gary and Beverly. We hit the road first thing in the morning before 9:00. It’s four turns off the interstate over fifteen miles of country road; I hope my signal holds up for the GPS to get us there. We’re going far away from the city center and deep into rural America, where we’ll be surrounded by farmland. Skies are clear, temperatures in the low seventies, a perfect day. We’ve flown across the country from Los Angeles and taken our fifth-grade daughter out of school to make the trip. But we’re banking on a big payoff: to witness just over four minutes of a total eclipse of the sun by the moon.

We’re met in the driveway just after 10:30 by Gary and Beverly, our hosts for the day. Over six feet tall, Gary towers like a venerable oak and has dark brown eyes the color of the soil beneath his feet. Beverly greets me with an honest-to-goodness hug—a real one, not some Hollywood air kiss—strong enough to restart a person’s heart if necessary. Her huge smile is the best welcome sign I’ve ever seen. Today, they’re in their element, as they will be surrounded by loved ones—their youngest daughter and her family, our family, several neighbors, and friends. It’s clear from the dozens of pictures all around their house that friends and family are what they treasure most.

Gary built their farmhouse with his father sixty years ago from the ground up: the walls, the floors, the kitchen cabinets, the stairs, the roof. I marvel at this jack-of-all-tradesman, who built his own home before graduating high school and retired several years ago after working more than four decades at General Motors, first as a factory paint supervisor, then in management. I’m reminded of family and friends from my childhood with similar unlimited skill sets. Notwithstanding my small-town Midwestern upbringing, I myself lack this trait; I wouldn’t trust myself to hang a picture on the wall. In fact, I’m the opposite. I live in one of the largest metropolitan areas of the country and have worked in a very narrow area of the law for nearly two decades. But when I close my eyes, I can slide back to that little town that’s still so much a part of me where I grew up, somewhere between north of Kansas City and the mythical River City south of the border of Iowa.

Green fields spill out in every direction around us. On every horizon across the hills and hollows are glades of maple, sycamore, and oak, or emerald pastures. There is no man-made thing other than gravel roads, telephone poles and power lines, and a handful of houses. It is the land that produces the food on our table from the wheat, corn, soybeans, and livestock it holds. It makes me think of my uncle’s farm we used to visit when I was a little girl. As a kid, everyone I knew either lived on a farm or had parents or grandparents who did. Unlike my life now, mostly uniform sunny days spent inside at a computer screen, in the heartland, your destiny is inextricably intertwined with the crust of the earth, the seasons, the weather. People who live here tend to have a profound respect for the elements because they know how bitterly harsh and destructive they can be—freezing winters with blizzards and ice storms, tornados in spring, and floods or droughts in the summer. A gorgeous, mild day—like today—is cause for celebration.

We all pile into open-air ATVs to head to a plot of land with a barn and farm equipment where Gary keeps the cows, all Black Angus, to watch him feed them. On the way back, we crest a hill with the pale stone country church where Gary and Beverly got married, where their parents got married, the cemetery next to it with their late relatives. Then, we sit on the lawn in arcs of lawn chairs and eat barbecued hot dogs and brats, salads, chips, and other snacks. Especially after running into a couple in our hotel who were headed to see the eclipse at an abandoned air strip with porta-potties, I feel most fortunate to be here with the hospitality and comfort of Gary’s farm as we wait for the moon to blink shut the eye of the sun.

But Gary and Beverly have not only made us comfortable; they’re sharing their story with us, which is tied to this land where they grew up, where they have continued to return over the decades from St. Louis where they worked and where their daughters went to school to farm the land and raise cattle. Gary tells stories about growing up just several miles from Beverly, about how he used to buy large Cokes at a general store when his bus stopped on the way back from high school that he’d share with Beverly. What I didn’t understand listening to similar stories from my own grandparents years ago was just how important these stories are, just like my own story I’m creating now that I’ll someday share with my own grandchildren. We come to wear our stories like favorite coats. They protect us against cold realities in their humor, warmth, hope, and love and, in their pattern and fit, they reveal who we are to our fellows.

Back at the farm, it’s a lazy day as the grown-ups talk and the kids, a half dozen from ages eight to fourteen, play. My eleven-year-old daughter falls in step with the other kids: looking for crayfish in the creek; trying to pet the barn cats that mostly run away; playing sardines in the hay bales. It reminded me of get-togethers from when I was growing up in the northwest part of the state, with friends, family, and neighbors gathered for whatever purpose—holiday, birthday, or just good measure, especially during good weather. And, this far away from the city, I’m forced to unplug and focus on the countryside around me since I’ve got no cellular connection or Wi-Fi. It makes me remember the joy of spending summer days outside at my grandma’s house in the garden and playing with the cats and rabbits.

Then, not long after 12:30, it starts. The sky gets noticeably darker. After 1:00, there are spindly shadows from the trees cast against the house as though it’s late afternoon.

Five years ago, a total eclipse passed over my hometown, but my family had already made plans to be in Northern California. Given that the next total eclipse wouldn’t happen again until 2044, I wanted to make sure we caught this one. The fact that it was happening in my home state also felt important: it was an opportunity to show my daughter some of her roots, the land where her grandparents, their grandparents, and their great-grandparents had lived for decades until I broke away to head to the West. Even though it’s been over twenty years since I’ve left this part of the country, I’ve gained a special pride about where I’m from, the little town where I grew up—like Perryville and the little towns so similar to it throughout the state and across the Midwest—where, for better or worse, everyone knows you. You can’t hide. You’re forced to make peace with your authentic self, claim it, and be willing to stand or fall on that. Like the moon making this chance encounter by crossing the path of the sun today, I wanted to cross this path again to show my daughter where I began my own story, what the land and life is like here in the Midwest. Being from the “Show-me state,” I appreciate the value of having her see it first hand.

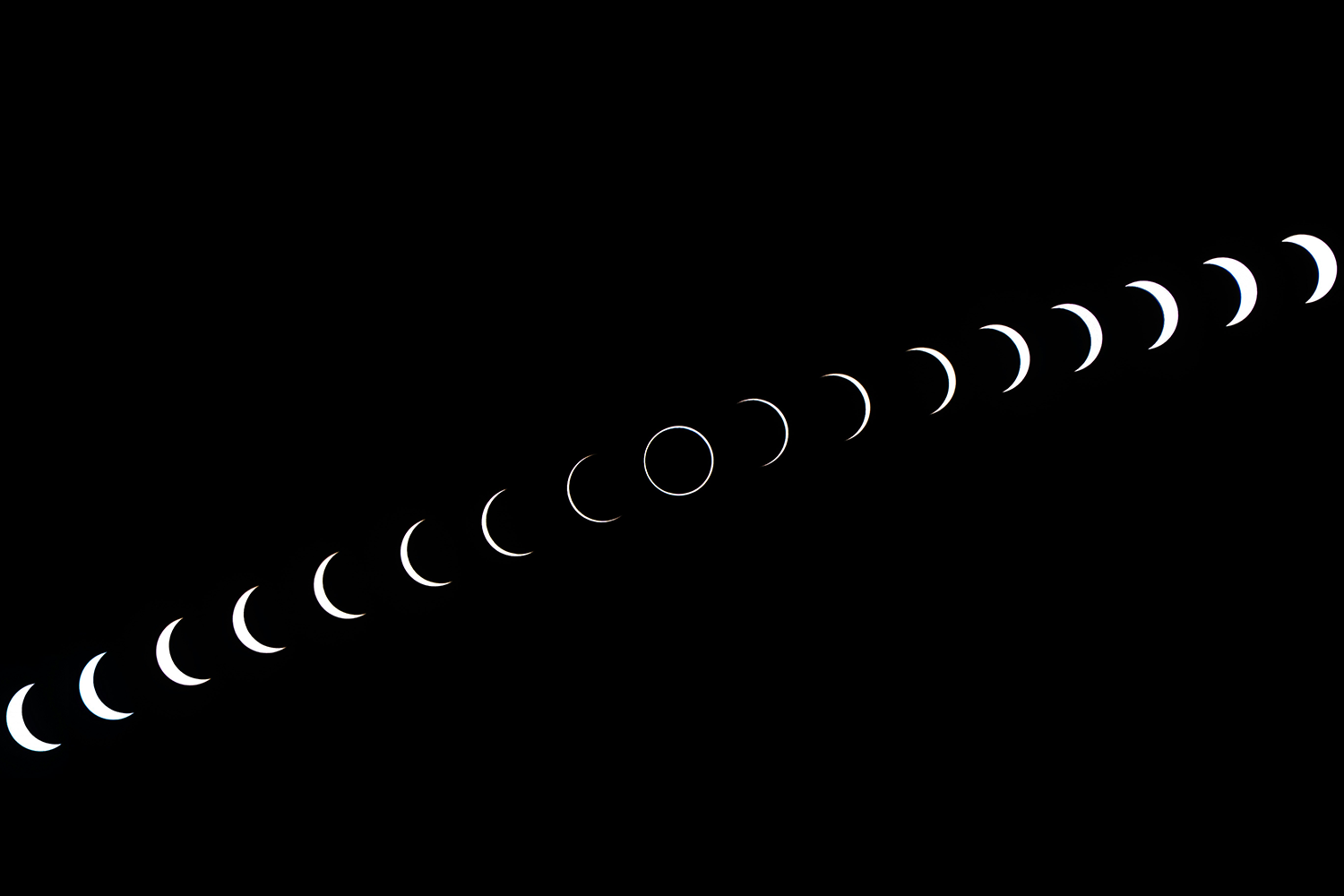

Then, not long after 12:30, it starts. The sky gets noticeably darker. After 1:00, there are spindly shadows from the trees cast against the house as though it’s late afternoon. Within fifteen minutes, the sky darkens more and a coral haze appears above the west horizon, as though the sun is about to set. A breeze sifts through the air. All the kids line up on the gravel driveway with their eclipse glasses looking at the sky. Through the glasses, the sun appears like an orange with a bite taken out of it, a bite that keeps getting bigger. As time passes, the air cools and the wind hastens. Newly budded leaves of the trees above us hiss as the breeze whips through them. The birds stop chirping and the crickets take over. By 1:45, the night-time security light switches on over the driveway. The trees become mere outlines against the fading sky.

It’s time to pop the champagne, I figure. Like midnight on New Year’s Eve, we’re counting down to 1:59, when totality is set to hit, watching the moon as it continues to overtake the sun.

Then, it happens. Darkness blankets the countryside as the moon slides over the sun like a pot’s lid. Black out. It is unassailable truth. The kids shriek. The adults smile at each other; none of us has ever experienced anything like this before. And we’re experiencing it first hand, not on a television screen. The sun is no longer visible through eclipse glasses, and it only appears as a white blazing ring the size of a button against the colorless sky, with nearby Jupiter and Venus appearing like stars. It looks as though a hole has opened up above us, as though all the light in the sky has been sucked out this tiny drain. Our skin looks ashen and eerie in the yellow light shining down on us from above the driveway, like we’re the undead risen from our graves after dark to walk the land until sunrise.

There is nervous laughter, mutters of “I’ll be!” or “What about that!” or “Isn’t that something!” There is no vocabulary for what we’ve just experienced but, from ages seven to seventy, I have no doubt that all of us feel something primeval, something that rattles our marrow. I look around at the kids, the horizon, the sky, trying to drink as much of the moment as I can, wanting to swallow this piece of time like the champagne in my paper cup. I wasn’t sure what I’d feel when I witnessed this event, but now I could only think, we are all here witnessing this, together, like what it must have felt like to take part in a prairie tent revival over a hundred years ago. Seeing is believing. But before I’m able to wrap my mind around my thoughts, it ends.

After the four minutes and several seconds of totality, the sun peeks out and, as we look again through our eclipse glasses, the thinnest sliver of it is visible. It’s as if someone has turned on the light again. A few minutes later, the security light goes off.

A few dogs come barking down the street towards us. After the kids pet them, they stop barking and go back home. They’ve been disturbed and disoriented by the daylight going out in the middle of the day; I can empathize. Even though I intellectually understand the reasons why the sky had just darkened, the raw animal being of me still feels ajar. I feel split in part, disconnected between heart and head. Everything made sense and made no sense, all at once.

Having the light of the world blotted out for four minutes made me stop and rethink things I take for granted. Just as the leaf is the tree, we are the Earth. It’s easy to forget going from place to place, errand to errand, that we make up a miniscule part of a colossal Universe. We dismiss the perfect order of things necessary for our existence that happen without any help from us at all: the moon spinning around the earth, the earth spinning around the sun, the planets revolving through our solar system. How much more important these things are shunts my trivial worries into stark perspective, like the white ring of the eclipse against the black sky.

During the slow car ride back to our hotel north on a crowded interstate, I think about why it felt so important for me to make this trip. We could have taken several trips to Disneyland with what we’ve spent on this trip, but Disneyland will still be there tomorrow, next year, the next decade. There’s nothing like a total eclipse to make you see that, even though you view the world from your own perspective, you’re part of something vast and profound, far beyond your own self, beyond our world, beyond our moon, beyond our sun, beyond our universe. I also want my daughter to know that there’s part of Missouri inside her connecting her there all the way from Los Angeles, like the path of the sun crossing over us each day. That we all have stories that help us make sense of the world when everything goes cold and dark, and Missouri will be part of the thread of hers. That we’re all connected and, more than that, the necessity of community. That when we seek community we look in a mirror and see parts of ourselves we may have forgotten, like the little Missouri girl from so long ago and the story of herself she was only just beginning. That rural America and urban America need each other; the world depends on farms and jacks-of-all-trades like Gary, as well as cities and specialists like me. That by coming together and sharing our stories with each other, we can make them more meaningful than they would ever have been on their own.

And that it’s amazing how little light can brighten the whole world.

Recommended

I Have Only Dreamed You Dead, For Now.

Encounter

Schizophrenic Sedona