“Touch the earth, love the earth”: A Review of Orion on the Dunes by Daniel G. Payne

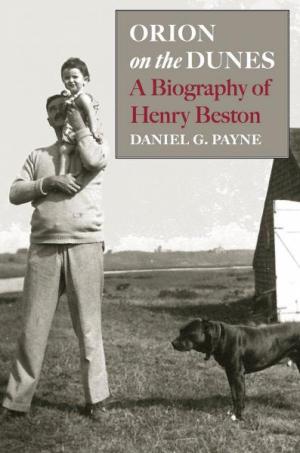

Orion on the Dunes: A Biography of Henry Beston by Daniel G. Payne, Boston: David R. Godine, 2016 Hardcover, 391 pages

Henry Beston’s The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod was published in 1928 to great acclaim and admiring comparisons to Thoreau’s Walden. Beston, like naturalist John Burroughs over a century earlier, did not much care for the comparison. As Daniel G. Payne says in this fine new biography, Beston also bristled when his work was compared with that of Burroughs, complaining humorously that he had been labeled a “thoreau-burrough.” Nonetheless, these annoying comparisons were early signs of Beston’s emergence as an enduring member of the company of literary naturalists—and The Outermost House as one of the classics of American nature writing.

Daniel G. Payne’s Orion on the Dunes: A Biography of Henry Beston fills a major gap in the study of nature literature. Admirers of The Outermost House and Beston’s other writings have been waiting a long time to see a biography of this unique and lyrical literary naturalist who holds a significant place in the history of American nature writing. I remember the impact The Outermost House had on me when I first encountered it decades ago— a great literary wallop, like a big Atlantic wave crashing in upon the reading self. As a student of environmental literature, I was immediately curious about this writer with his energetic and lyrical voice, and wanted not only to read more of his work, but to know more about him. Eventually I learned that he had been married to Elizabeth Coatsworth, a children’s author and poet whose books were precious to my childhood—which made me even more curious. Two beloved writers married to one another!

When I learned some years ago that Daniel Payne was writing a biography of Henry Beston, I could hardly contain my eagerness to read it. Patience was required, however, for Payne’s research was painstaking and scrupulous; his writing has the elegance and care of the finest biographies. Even after it was completed, and his book was slated for publication by David R. Godine (Beston’s own current publisher), the wait continued through Godine’s fastidious process of seeing a book into print.

Orion on the Dunes proves well worth the wait for longtime admirers of Beston’s work—and a fine introduction for newer readers. Payne begins his biography with Beston (then Henry Sheahan) as a volunteer ambulance driver in France in World War I—a surprising opening to the biography of a naturalist, but one whose relevance is made clear throughout the rest of the book. Indeed, throughout Orion on the Dunes, Payne takes care to place Beston’s individual life within its historical setting in a century of many dramatic events. To read this book is also to enjoy a thoughtful review of the history of twentieth-century America. Although Beston wrote so beautifully of the timelessness of nature, he remained very sensitive to world events; his horror of war, born of his experiences as an ambulance driver, affected him throughout his life, sometimes skewing his political positions, such as his opposition to US entry into World War II, in odd but understandable ways.

One of the things that surprised me most as I read Orion on the Dunes was how much this deeply poetic writer of non-human nature was influenced by very human public affairs, not only on environmental and conservation issues, but also political ones of general governance and war and peace. As Payne’s portrait makes clear, Beston was always concerned with the relations between human beings and nature—and our obligation not only to protect nature, but to learn from it, to be worthy of it; to be healed by it. Less surprising perhaps, is that Beston, with his deeply mystical love of nature, was a particularly sensitive soul, who chafed when away from nature or under too much worldly or familial stress, and who could be quirky and irritable at times; and yet he was also a genial, loving and kindhearted man. Payne presents him in his entirety, with an unfailingly understanding narrative, tactful, and yet truthful, an excellent example of the art of biography.

Beautifully and symmetrically structured, Orion on the Dunes builds from the beginning chapter in World War I through other events and periods of Beston’s life, including his early writings as a journalist and his experience as an embedded reporter on a Navy ship, which resulted in the book, Full Speed Ahead. (In fact, an essay that first appeared in the North American Review in November 1918, “With the Convoy,” was reprinted in Full Speed Ahead.). Payne also covers Beston’s surprising gift for writing fairy tales that were compared with the work of Hans Christian Anderson, analyzing these stories quite charmingly, to show how they fit into Beston’s philosophy. His interest in “Gallant Vagabonds,” which led to his volume of brief biographies of adventurers not unlike himself, is also described aptly by Payne. From this gradual and careful building, the biography reaches its pinnacle at the center of the book in the brilliantly written chapter “Orion Rises on the Dunes,” depicting the experience, writing process, publication, and reception of The Outermost House, Beston’s enduring masterpiece. This chapter alone is worth the price of admission. The later chapters function in some sense as dénoument, falling away from that main height of achievement and excitement, while remaining immensely compelling. In these later chapters Payne presents the accomplishments of Beston’s later writing, despite periods of anxiety over the difficulty of living up to a work like The Outermost House (accomplished works like The St. Lawrence and Life on a Maine Farm); the significance of his role in twentieth-century nature literature; the rich experience of his marriage to Elizabeth Coatsworth; and the issues and concerns of his later years. Throughout, Beston’s deep and evolving relationship with nature is a constant presence—like the stars and constellations that he so loved and that inspired the title of Payne’s book.

When I first held Orion on the Dunes in my hands, I succumbed to an old scholar’s habits, looking first at the extensive endnotes and bibliography, as well as the insightful organization of its chapters, and felt a surge of admiration for the careful scholarship that had clearly gone into this work. But when I finished reading, my thoughts were much deeper. With his own extensive knowledge of American nature literature (he is the author and editor of several books of ecocriticism), Daniel Payne is able to place Beston within the context of other naturalists and environmental writers, from John Burroughs to Rachel Carson. (One of this biography’s lovely discoveries is that Rachel Carson had been greatly inspired by Beston’s work.) In addition, Payne writes with something like a poet’s sensitivity to Beston’s consciousness and to his often mystical approach to nature. He quotes abundantly from Beston’s writing, so that the reader’s impression is strengthened not only by the narrative of the biography, but also by the presence of Beston’s own voice. An example of Daniel Payne’s artistic approach to this biography is his practice of opening each chapter with an epigraph, usually a passage of poetry, that conveys something essential about the contents and mood of that chapter. But the real distinction is in the writing itself. Throughout Orion on the Dunes, the reader feels in the presence of a perceptive, knowledgeable, reliable and gifted narrator.

One moving example of this masterful writing is in the lengthy description of a ceremony late in Beston’s life, honoring the Fo’castle as a literary landmark and The Outermost House as key to the establishment of the Cape Cod National Seashore. Payne’s narrative beautifully conveys this touching and satisfying culmination of a deeply questing writer’s life and work. Henry Beston always said that his most important value was that he was “on the side of life.” The depiction of this powerful moment conveys not only the significance of being on the side of life, but also the poetry. It is perhaps emblematic of Payne’s self-effacing approach to this biography, that he allows other voices to have their say—observers of the event in question, or Beston’s wife Elizabeth for instance, and quotes at length the passage that Beston himself reads to the crowd at the ceremony—the powerful last paragraphs of The Outermost House, which concludes,

Touch the earth, love the earth, honour the earth, her plains, her alleys, her hills and her seas; rest our spirit in her solitary places. For the gifts of life are the earth’s and they are given to all, and they are the songs of birds at daybreak, Orion and the Bear, and the dawn seen over ocean from the beach.

While Payne has constructed the moment artfully, through the voices and perspectives of those present, his own description is touchingly simple:

A short time later, five beach buggies carrying the Bestons and dignitaries from the ceremony—which Beston humorously referred to as "the coronation"—made their way from the amphitheater to the beach, where they traveled about a mile before stopping at the Fo’castle. Numerous reporters and other visitors followed along and watched as Elizabeth Coatsworth and Governor Peabody helped Beston from the car and supported him as he walked slowly up the steps to the dune shack.

One has already been moved almost to tears, experiencing along with Henry Beston his final moment of crossing the threshold into his own “outermost house,” when Payne gently tells us, “When the crowds cleared and dusk fell, the Bestons got back in their car for the long, slow drive back to Maine and Chimney Farm.”

For telling his life story and inspiring readers to return to his work, Henry Beston could not have asked for a better biography than Orion on the Dunes, nor a better biographer than Daniel Payne.

Charlotte Zoë Walker is a former NEA Fellow in Creative Writing, and O. Henry Award winner. She has published a novel, Condor and Hummingbird, as well as numerous essays and short stories, including “The Very Pineapple” (Prize Stories 1991: The O. Henry Awards), and “Goat’s Milk” (listed among “100 Distinguished Stories” in Best American Short Stories, 1993), She is the editor of two books on naturalist John Burroughs published by Syracuse University Press, Sharp Eyes (2000), and The Art of Seeing Things (2001), and much of her writing is influenced by the natural world of upstate New York. Her current project is Gray Face and Eve, a novel about a 12th century stone carver as told by his sculpture of Eve.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop