A Review of Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America and Coming Alive: Action and Civil Disobedience

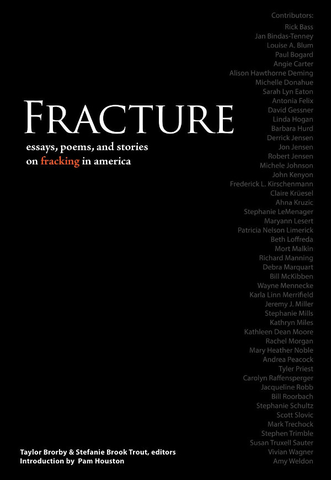

Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America, edited by Taylor Brorby and Stefanie Brook Trout, Ice Cube Press, 2016, 488p, paperback $24.95

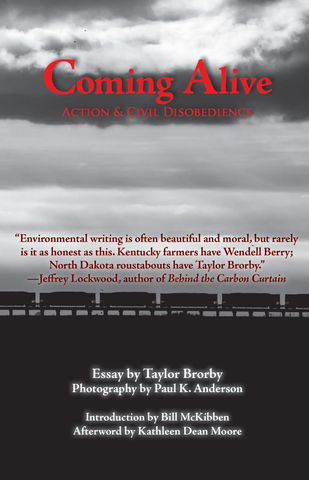

Coming Alive: Action & Civil Disobedience, by Taylor Brorby, Ice Cube Press, 60p, paperback $10.00

I’m aware that it might seem too terribly self-congratulatory for an editor such as myself to note that the work of an editor is, at heart, altruistic (you’re welcome), but I can say with a perfectly clean conscience that an anthologist’s work is always an act of literary gift-giving, for which readers should be grateful. Such gratitude is best expressed in cold cash, sent forthwith to fine literary publishers like Ice Cube Press, which late last year produced an artful, compelling, and necessary book in Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America, edited by Taylor Brorby and Stefanie Brook Trout, two young writers whose work promises great things for our reading futures.

Fracture is also, of course, timely as well, coming as it does in the midst of the continuing protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota, prompting any sane and reasonable person to think deeply about the sweeping implications of human dependence on (one is tempted to say addiction to) fossil fuels.

The poems gracing the pages of this anthology make the book worth the price of admission. Debra Marquart’s “Small Buried Things” (from her latest collection of the same name from New Rivers Press) updates Ginsberg’s equally pointed political poem “America”:

north dakota i’m worried about you

the companies you keep all these new friends north dakota

beyond the boom, beyond the precious resources

do you really think they care what becomes of you

The North American Review’s own poetry editor Rachel Morgan’s contribution to Fracture takes us on “An orbital tour of cities at night,” artfully strange but revealing, where we witness “In the fracking fields burn-off glows / and roads connect, but lanes and places / lead nowhere.” (I may be partial—sorry—but I think Rachel’s masterful poem is the star of the show!) Linda Hogan’s “Greed” reminds us that “gravity has its own desire / to call us into the ground.” What we find in the ground is hopeful but uncertain:

Something yet holds purchase, holds sway

in a world filled with green trust, even the blade

of grass recalls how

to grow back its original blade.

But I don’t know what tide is arriving

from the greed of American soil.

Just like for mineral,

now the search between rock, flint,

shale.

It’s hard not to think now of other deeply troubling movements that gain their energy and fervor “from the greed of American soil.” Nationalism, Americanism, Make-America-Great-Again-Ism—whatever you call it, it’s charged with race in ways that some are still unwilling to admit. Can we dispute that the roots of ecological devastation and racial discrimination are one? Can we deny that environmental injustices are a result of entrenched historical patterns of racism? Can we?

This anthology offers very convincing, straightforward descriptions of fracking (short for the phrase “hydraulic fracturing”) from the likes of Frederick Kirschenmann, Bill McKibben, and Tyler Priest, as well as compelling surveys of the discourse surrounding fracking from Patricia Nelson Limerick, Kathleen Dean Moore, and others. The more personal narratives, however, invite me more persuasively into these pages, like Rick Bass’s essay “The World Below,” which serves multiple functions at once, teaching us about fossil fuel industries, telling an autobiographical journey of self-discovery, and calling us to action: “I don’t understand why everyone in the United States is not hand-cuffing themselves to the gates of power. We can no longer pretend we don’t know what is happening. We know what’s happening and it’s time to act.”

Similarly, Taylor Brorby’s “White Butte” appeals to our need for the personal, telling the story of his attempt to get outside of the boomtown of Dickinson, North Dakota, to hike and climb buttes. The essay revels in the land, attentive to its contours and peculiarities:

“The soil crusting White Butte crumbles beneath our feet. Already in May the earth of western North Dakota is dry. . . . The path banks right, dipping below the ridge and pressing against orange and green lichen-covered scoria rocks. I touch the rock, press my fingers into the water-worn holes, notice the fine sand sitting in the rock’s pores. How long has the wind and water been at work on White Butte? I wonder.”

This sense of wonder and awe in the presence of the nonhuman natural world animates all of the contributions to this anthology, and it also serves as the ultimate source of inspiration for Brorby’s other powerful new book, published by Ice Cube Press early this year, Coming Alive: Action & Civil Disobedience, which can very much be considered an illuminating companion to Fracture. In the essay, he narrates the process by which he eventually becomes an environmental activist, an identity he never intended to embrace. “What I really want,” he writes, “is to be is a homebody—to read, write, and struggle to make art. But my home in North Dakota is on fire.”

Brorby details his arrest while protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline in Pilot Mound, Iowa, and describes his visit to Standing Rock, intertwining with these narrative threads the story of a car trip in the Bakken in North Dakota with his young nephew Logan. In the end, this pocket-sized book challenges all of us who care about the planet to work on its behalf, to “come alive,” as Brorby puts it: “Coming alive is a way of noticing, a way of listening, it is to understand one’s responsibility to others, even nonhuman others, and then to act in a sacred way of radiating outward, of growing magnanimous.” This magnanimity, he argues, this generosity of spirit, this ecocentric connectedness is what can save us. The activism at the heart of both Fracture and Coming Alive offers not only hope and comfort in the face of deflating political realities but also much needed inspiration to go forth and fill the gaping silence and acquiescence of the unsustainable status quo with fierce voices of protest.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop