“Tracing the shape of real bodies”: An Interview with Frances Cannon

I used to watch you paint faceless forms

with translucent skin and paper bags for heads,

appliances with vibrant organs,

greyhounds with rows of nipples like teeth

and so many legs they can’t walk.

Is the typewriter still whining, purring, clicking

its tongue in your lap? I timed my breath

to the beat of your poems in order to sleep.

—Frances Cannon, “Fling Diction”

Fling Diction by Frances Cannon (Green Writers Press), is a poetry collection published in February of 2024. The collection, through visceral imagery and delightfully spun lyric narratives, weaves together moments of queer love, familial bonds, heartfelt reflection, and longing. Bordering at times on surrealism, visual art and the natural landscape appear throughout the poems to complement and uplift moments of deep vulnerability and honesty. Vibrantly alive, this is a collection driven by passion and intimate observations.

Greer Engle-Roe: I’m always interested in book titles, and how they come to be. Of course, within the collection you have the title poem, “Fling Diction.” Did you always have that title in mind for the collection as a whole? How did you arrive at that title? It’s a beautiful title.

Frances Cannon: Thank you. The poem “Fling Diction” involves two writers involved in a romantic fling after a writer’s conference, and how their intimacy is wrapped up in the particulars of language, thus, fling diction! The title felt right for the collection as a whole—many of the poems explore the complicated, difficult, and often delightful aspects of living a queer, polyamorous lifestyle (fling), but the poems are also about the writing process, academia, and communication (diction).

GER: In the collection, many things seem to be in a momentary state, either before leaving, or while passing by: passing lovers, homes, different places, and artworks. In your poem, “Déjà Vu,” it rises to the fore as the speaker wonders about where they’ve seen this person that they’re watching, and recalls different memories of where it could be. What inspired you to write about these moments of passing within the collection?

FC: My life has been rather chaotic up to this point in time, and the chaos continues—sometimes I feel like a cat that has already passed through most of my nine lives. I have lived in many places, worked many odd jobs, and loved many people. The poem “Déjà Vu” follows a character who may or may not exist, through various significant moments in my life. They represent my shifting desires but also my continuous curiosity about queerness in community and partnership.

GER: Within the collection, there’s such openness in detailing passion, and love, in many different forms. There’s a focus on visceral touch. Was there a balance that you had to strike between allowing the reader so close to those intimate moments within the poems?

FC: Great question—I have been reading and enjoying many books by contemporary queer authors who champion the realness of writing about queer sex, in all of its real, gritty, sometimes painful or confusing moments of intimacy. For example: Garth Greenwell, Alexander Chee, Sabrina Imbler, Allegra Hyde, K Patrick, Chris Belcher, Alyssa Songsiridej—these authors are writing very vivid sex scenes that are also literary, nuanced, and thought-provoking. That’s my goal in my poems; I wanted to trace the shape of real bodies in honest, lived-in scenes.

“Sometimes, if I’m going through a difficult time, such as a moment of longing or frustration, writing a poem brings a sense of closure and/or release. Catharsis in action.”

GER: Throughout the collection, in poems such as “Pursuit of a Tiger,” “Cosmopolitan Swine,” and “Beware the Birds,” the boundary between humans and animals becomes blurred. Characters take on these bestial traits and forms, sometimes fully transfiguring themselves. What draws you to that connection between us and animals, and in a broader sense, the natural world?

FC: I’m currently teaching courses in science and nature writing at Kenyon, and many of the books, essays, stories, and poems that I am drawn to and which my students enjoy discussing involve human and nonhuman animal relationships, either in metaphorical comparisons or direct interaction, such as Imbler’s How Far The Light Reaches in which the author draws connections between their queer community and sea creatures, or in Donna Haraway’s writings about companion species and naturecultures, in which humans and nonhuman animals are always intertwined. I also enjoy this concept in fiction and dreams; a tiger figure often appears in my dreams, and it brings to mind the dystopian short story “The Caress” by Greg Egan, based on the painting “The Caress of the Sphinx” by Fernand Khnopff, 1896. I suppose all of these books, texts, dreams, and art seep into my subconscious and bubble up when I’m writing poems.

GER: In the last section of Fling Diction the imagery turns increasingly to plant life, almost as a form of cataloging all the plants and fungi that appear around the speaker. How much specific research do you do before sitting down to write your poems, or do those references and names come naturally to you?

FC: I’m always learning, and am never an expert. I enjoy gathering knowledge about the natural world, particularly plants, mushrooms, and animals. This biophilia runs in my family: there are botanists on both sides of the family, both professional and amateur, and my current partner is a botanist. The passion for collecting names of plants is infectious. I also am an avid forager, particularly of mushrooms, and it’s important to learn about the wild things you’re harvesting, particularly if you’re going to eat them!

GER: I was really interested in the poem “Nabokov's Ecstasy” which does an erasure of Nabokov’s “Butterflies” piece. What drew you to that individual piece, and the form of erasure?

FC: It is such a lovely essay. I’m utterly devoted to The New Yorker, and it’s the only publication that I subscribe to and regularly read—it contains so many gems of perfect literary writing, as well as science and nature writing. Nabokov was not only a creative writer but also a lepidopterist, and his essay-memoir about his life in pursuit of butterflies struck me as pure delight. My erasure of his piece is a translation of essay into poem. In the simplest sense—I plucked out images and musical phrases to convey the gesture of his memories in a few breaths rather than in half a dozen pages.

GER: I’m curious about how you view the piece’s transformation from the original essay to the poem, can you find a piece of yourself within it?

FC: Absolutely, yes! I love that Nabokov acknowledges his own absurdity in the essay, in the line “The older the man, the queerer he looks with a butterfly net in his hand.” If I am alone in the woods, squatting down over a log, examining a slime mold, and a stranger happens to walk by—I feel very odd indeed, although I don’t mind that feeling of nerdy otherness, and I doubt that Nabokov minded much either. I also admire his obsessive passion for the ‘hunt’ for butterflies, which I have felt while mushroom foraging, while examining moss or wildflowers, and other modes of natural inquiry.

GER: On your website, you spoke a bit about your process of creating your book of illustrations, Image Burn. One line that stuck out to me was when you wrote, “My challenge in this endeavor was how to merge two artistic realms—poetry and printmaking—and produce a third aesthetic experience that is greater than the sum of its parts.” Can you speak a little bit more about that goal? How do you view art and writing to merge in general, and in Fling Diction?

FC: This is often the challenge in book arts and hybrid mediums, such as in graphic literature—the artwork should tell its own captivating story and carry a visual narrative that works in tandem with and in support of the text, but is also unique and independently interesting. The flipside of this is illustration, which is often a simple reflection of the text. I enjoy a book in which the art and the text work together, so to speak, to tell an enhanced and more in-depth story.

GER: Are the small drawings at the beginning of each section in Fling Diction your own?

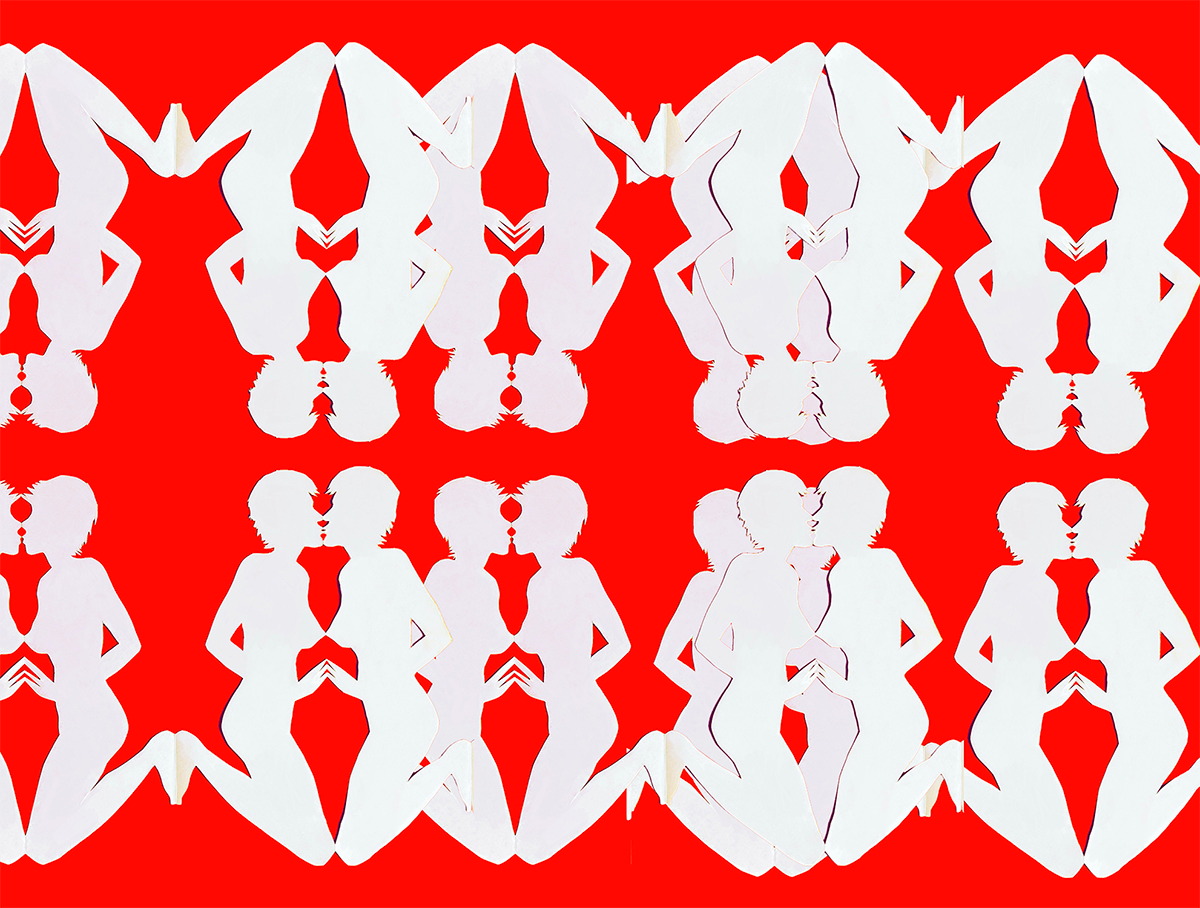

FC: All of the artwork associated with this book is my own—the cover idea came to me during a bout of insomnia—paper doll cutouts of ambiguous androgynous figures—are they lovers or various reflections of the self? The drawings were a lot of fun to create for this collection.

GER: There’s an astounding eye for image and metaphor within your poems, with lines such as, “Don’t look at your hands while juggling; / they should appear blurred, gesticulating skyward / as if rearranging the heavens. The Pleiades constellation / disappears the longer you stare.” What do you think crafted or honed that eye? Does it come from your visual arts background? Or a writer/artist that you were particularly inspired by?

FC: I am a voracious reader and art witness, and so it would be difficult for me to discern one or two primary sources of inspiration throughout my life in art and letters. Yet, I’ll try! Some authors that I return to often: Marilyn Robinson, Virginia Woolf, Patricia Highsmith, Donna Tartt, James Baldwin, Alison Bechdel. Visual artists: José Antonio Suárez Londoño, Louise Bourgeois, Ruth Asawa, Hilma af Klint, Lynda Barry, Swoon, Paula Rego, Amy Cutler, Ernst Haeckel, Francis Hallé, Alexander Calder, Leonard Baskin.

GER: Do you recognize moments that you want to write about while you’re walking around? Or do they arrive afterwards, while you’re writing? You mentioned, previously, the influence of dreams on your poems.

FC: Sometimes I give myself prompts, which come to mind often given that I’m a creative writing professor and I give similar writing prompts to my students each week. If I experience writers’ block, I’ll ask a friend for a prompt. Sometimes, if I’m going through a difficult time, such as a moment of longing or frustration, writing a poem brings a sense of closure and/or release. Catharsis in action.

GER: As a final question, do you have any projects coming up that you’re excited about?

FC: I am thrilled that later this year, Green Writers Press will publish a children’s book, Willow and the Storm—my good friend Ethan Tapper wrote the story, and I created the art and helped edit the book. Beyond that, I have a novel that I’ve been crafting and editing for several years which I hope to publish soon. Stay tuned!

Recommended

An Interview with Ren Cedar Fuller

Becoming Visible

A Conversation with Ted Kooser: In Dialogue with Judith Harris