The Lesson

Everything I tell you is a lie. Do you believe me?”

“No way, Mr. M.,” a student says.

“Then it must be true.”

“Wait... what?”

Another says, “I’m confused.”

A third, “My brain hurts.”

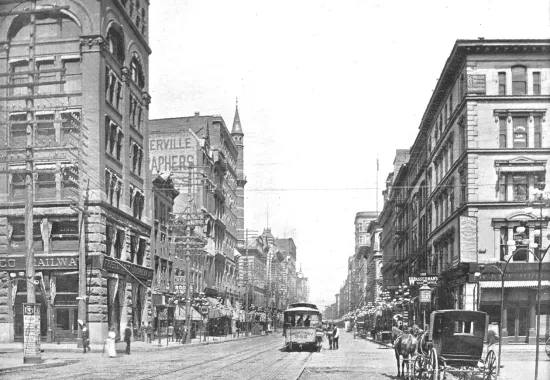

It’s the day after Labor Day, the first day of the 2001 school year at Atlantic City High School. My period one creative writing class, an elective for juniors and seniors, has just begun.

“Confused is good,” I say. “And that pain in your brain, that means you’re thinking.”

Lea is absent. She’s a senior who’s taking the class a second time because she likes to write and is good at it. Her parents are pissed off at her, and at me, because she’s decided to major in creative writing in college. They’re professionals who expect her to follow in their footsteps. Last year they showed up after school to talk to me. Her mother said, “We’re afraid Lea might become unemployable, or worse, an English teacher.” She insisted I talk her out of it. “Tell her if she wants to write poetry she can do it on the weekend.”

I argued that studying poetry will help Lea become a better reader and writer and a more fluid thinker. Plus, she’ll develop language skills that will give her an advantage in whatever career she chooses, even teaching. They didn’t buy it.

When my own artsy kid, who planned to major in dance, switched to engineering, I thanked the universe. I’m a hypocrite, I know. I can live with that.

“An artful lie,” I say, “is a backdoor way of revealing a truth. And your job as writers is to tell the truth.”

Lea shows up the following Tuesday. She asks to speak with me before class. She’s petite, smart, and funny. Despite the warm weather she’s wearing a black leather jacket. I can’t tell if it’s real or fake. I can never tell. “Where’ve you been?” I ask her.

“I spent the summer in rehab, Mr. M. I got home last week, but I couldn’t deal with school.”

“Rehab?”

“Yeah... I was drinking under the Boardwalk with some out-of-town boys I didn’t know and passed out. You can guess what happened next.”

“Oh . . . I’m sorry.”

“Mr. M...” she hesitates, placing her backpack on my desk, “if I need to leave school early to go to an afternoon AA meeting, would you write me a pass so I don’t get flagged for cutting eighth period? It's only chemistry. Not every day, but . . . I’m trying to stay sober.”

“Shouldn’t you ask your guidance counselor?”

She tells me his name and says, “Really? You think he’d give me a pass?”

She’s right. He’d never write her a pass. “Okay,” I say, hoping she’s not playing me, “but don’t abuse it.”

“Thanks, I won’t.” Then she says, “Mr. M., you know about the Thirteenth Step?”

“Thirteen?” I hesitate. “I thought there were twelve.”

“Don’t come to these meetings to get laid,” she says, “’cause you’ll only get fucked.”

“What!”

“I’m usually the youngest one there, and I’m pretty, and I look innocent, which means some of the old guys think they’re going to get lucky. They’re like flies around horseshit.”

Lea has grown up over the summer. Too much, and it saddens me. I watch her find a seat, put down her backpack, and take off her jacket. Her T-shirt says, “This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours.” It’s the title of an album by The Manic Street Preachers, a Welsh band I played in class last year. She pulls out her journal and a pen and looks up, ready for whatever comes next.

I introduce metaphor by instructing the students to write lies, which can kickstart the imagination. “An artful lie,” I say, “is a backdoor way of revealing a truth. And your job as writers is to tell the truth.” They go for it.

“I was raised by a coven of dragons,” writes one.

“It’s raining so hard even the flounders are drowning,” writes another.

“My armpits are upside down birds’ nests,” writes a third.

“Good! Good!” I say, encouraging them as I walk up and down the aisles. “Keep writing.”

I then instruct them to write a poem beginning with one of their lies. In their next draft, I’ll ask them to remove the lie and see if the poem works better without it. If it doesn’t, they can always put it back.

Near the end of the period, Mrs. B, the Spanish teacher across the hall opens my door and sticks her head in. She looks ill. Crap, I think, she probably wants me to cover her class during my free period. I walk over.

“Did you hear the news?” she whispers.

“What news?”

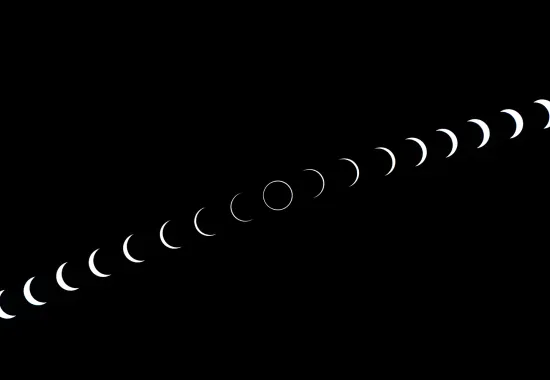

“A plane flew into the Twin Towers.”

“What!”

The passing bell rings. As the students get up to leave, they ask what happened.

I look at them, stunned. “A plane flew into the Twin Towers,” I say.

“Good one, Mr. M.,” laughs a student.

“Nice lie,” says another.

“I’m telling the truth,” I protest.

“Yeah, right,” says a third.

Lea is last out the door. “I don’t know, Mr. M.,” she says looking up at me. “Sometimes I don’t know whether to believe you or not,” then disappears into the hallway traffic.

Recommended

The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

A Picture of Stack Lee

Crossing Paths