Between the Personal and Political: Writing the Stories of Gay Liberation

I am very grateful to North American Review for publishing the poem “I Heard They Were Queer for One Another,” featured in the 2015 spring issue of NAR, as it is part of a project that is very near and dear to my heart. In the introduction to Carolyn Forché’s landmark anthology Against Forgetting, Forché advocates for a space between the categories of the personal and political poem—a space that she calls “the social.”[1] I have always liked the implications of this. That between the personal and the political there is conversation, gossip, culture, socializing. A fertile ground for poetry indeed! That space Forché describes is where I wanted this poem to reside.

The personal: I came out of the closet in high school, so I feel intimately the desire of individuals to carve out a space that is private, separate from politics and the media’s glare. I’m also aware that the act of carving out such a space can be a political gesture. That’s perhaps why I became so fascinated with the story of the Stonewall Riots of 1969. It wasn’t until I was a junior in college that I learned about the Stonewall, the efforts of Gay Liberation, and I remember being shocked at the time that I had lived as long as I had having never caught a whiff of any of these narratives or histories. It wasn’t even in a classroom or book that I learned about them, at least not at first, but rather through word of mouth, interactions with older gay men in the community who knew a thing or two about gay history. At the time (the late 1990s) it seemed that gay and lesbian history was an idea that was still trying to take shape. The commotion made by this silence (and silence can indeed make a lot of noise) propelled me into this project. I wanted to make sense of these stories, and perhaps more importantly, I wanted to make sense of what they meant to me. How was I a part of this history? How much of my life did I owe to these men and women?

The political: So a word on the Stonewall. The Gay Liberation movement is said by many to have started on a hot summer night in 1969 in New York City’s Greenwich Village when a group of street kids with few options and nowhere else to go chose to resist police harassment of known homosexual establishments. The poem “I Heard They Were Queer for One Another” is a piece included in my most recent poetry collection What the Night Numbered (Trio House Press, 2015), wherein the myth of Cupid and Psyche—their epic account of love discovered, lost, and eventually reunited—is re-envisioned and threaded with the accounts of the Stonewall Riots. The voices that speak within these poems are those of the oppressed and unnamed, those who live between the traditional categories of sex, gender, and sexuality in a time when the only names given to such individuals were slurs. Many are the voices of street kids and queer youths, hustlers, panhandlers, and survivors who have come to New York in search of both the city’s great anonymity and the promise of a space, however meager, to meet and love one another. The spirit of these youths are vocalized in the character of Psyche, the name given to a transgendered runaway from Nebraska who comes to the urban streets at the age of thirteen with only the clothes on her back, a fist full of faux jewelry, and a desire for a new kind of love.

The poem featured in this issue of North American is set at the moment when the crowd and commotion outside the Stonewall Inn became a riot. On June 28, police raided the bar. The riot trucks idled outside waiting to be loaded with the patrons, all of whom would be arrested, their names published in the paper, which meant jobs would be lost, marriages would implode, and lives would be ruined. This was nothing new. Raids were a part of life during this era in gay culture, but for whatever reason, on this night the patrons, many of them those street kids mentioned above, had decided enough was enough. The poetic speaker in the poem is a kind of collective voice—the voice of those street kids gossiping about what happened, speculating, but the poem watches the police. Once the riot started, the police were forced inside the Stonewall, barricaded inside. There was only one exit, and they were ordered by their superior to wait for help to come.

The social: I wanted this poem to tie the experiences of those officers to the lives of those rioters beating on the doors of the Stonewall. I wanted to show a point of connectedness in the midst of chaos, the one side reflecting the other. Brutality is always easier when we deny our commonalities, and so I chose to make everyone present bound and intimate, even as it all came apart. As this brotherhood of officers stands together facing their fears of what might await them on the other side of that door, they effectively mirror the fears of the Stonewall’s patrons who often faced daily homophobia and potential police harassment. Effectively, in that moment the police are queered. They are made strange, or perhaps more accurately, they are brought into the strange—that liminal and uncertain space at the margins. They feel their power slipping away, and they are oppressed. I would like to think that for a moment the two groups psychically approached one another, perhaps recognized themselves in each other’s faces, and I’d also like to think that it was indeed the queerest thing.

[1] Carolyn Forché, introduction to Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness, (New York: W. W. Norton, 1993), 31.

Bradford Tice is the author of two books of poetry: Rare Earth (New Rivers Press, 2013), which was named the winner of the 2011 Many Voices Project and a 2014 Debut-litzer finalist, and What the Night Numbered (Trio House Press, 2015), winner of the 2014 Trio Award. His poetry and fiction have appeared in such periodicals as The Atlantic Monthly, North American Review, The American Scholar, Alaska Quarterly Review, Mississippi Review, Epoch, as well as in Best American Short Stories 2008. His poetry was also selected as the winner of Prairie Schooner’s 2009 Edward Stanley Award. He currently teaches at Nebraska Wesleyan University in Lincoln.

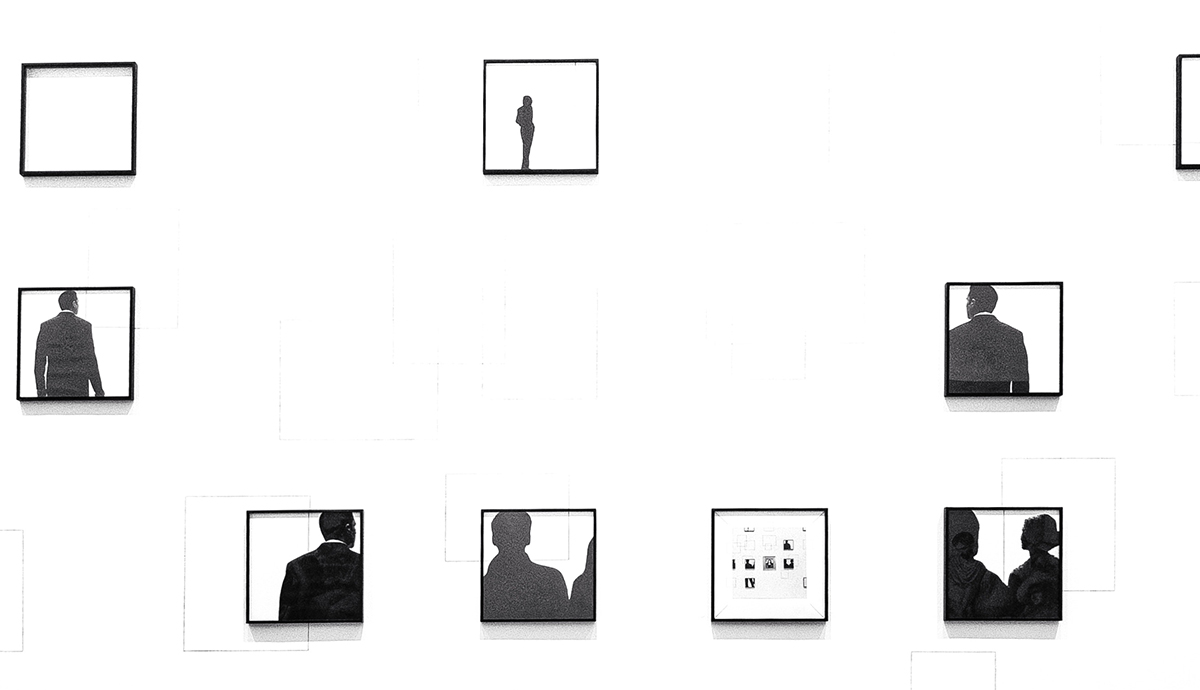

Artist: Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review issues 298.4, 299.1, 299.3, 299.4, and most recently 300.2, Spring 2015.

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings