Black Lines

There are a few constants in the many years since I have been trying to write seriously. One, of course, is the struggle to find a time to write, which has varied over my years in college, medical school, residency training, and practice as a physician. Despite massive changes in technology—moving from spiral-bound notebooks to an electric typewriter to a primitive IBM PC with two floppy disk drives to various cranky Compacs, Gateways, and Dells, and finally to my current sleek MacBook Air—I’ve always been able to find some time to put my thoughts into words. Perhaps a few minutes here and there, perhaps hours fitting into my hospital day, the time and mental space have somehow emerged regardless of current circumstances. And somehow, over the years, this has resulted in an accumulation of essays (many have appeared over the years in the North American Review), stories, articles, books, and these days, blogs and postings too.

Something equally constant in my life has been water. Since high school, I have been a serious swimmer. My pools have changed from one year to the next, in some strange way parallel to the changes in my writing media.

I began, naked, thrown into a chilly pool with other five-year-old boys at a strict summer camp. I must have emerged with a love of water. I swam in Ys and JCCs. I swam in lakes in Maine and northern Ontario. I swam in dozens of pools. There was the narrow two-lane public pool in North Beach, San Francisco, where I could look out on old Italian men playing bocce. There was a beautiful pool on a plateau below the just-captured Golan Heights, at the kibbutz where I spent a summer picking apples and chasing Israeli girls. Then, most spectacular of all, there was a gleaming turquoise fifty-meter outdoor pool on the Stanford University campus with a grassy bank along one side, where I’d sit after doing my mile, either reading Gray’s Anatomy or short stories by my graduate fiction writing workshop classmate Tobias Wolff. A few years later, there was a grim Midtown Manhattan pool with sulfuric-yellow water and fearsome denizens of the shattered locker rooms. And then, the fiercely competitive pool at the 92nd Street Y, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, with slow, medium, and fast lanes, where you needed to choose your spot carefully and keep up the pace at risk of getting kicked in the eye.

I began, naked, thrown into a chilly pool with other five-year-old boys at a strict summer camp. I must have emerged with a love of water. I swam in Ys and JCCs. I swam in lakes in Maine and northern Ontario. I swam in dozens of pools. There was the narrow two-lane public pool in North Beach, San Francisco, where I could look out on old Italian men playing bocce. There was a beautiful pool on a plateau below the just-captured Golan Heights, at the kibbutz where I spent a summer picking apples and chasing Israeli girls. Then, most spectacular of all, there was a gleaming turquoise fifty-meter outdoor pool on the Stanford University campus with a grassy bank along one side, where I’d sit after doing my mile, either reading Gray’s Anatomy or short stories by my graduate fiction writing workshop classmate Tobias Wolff. A few years later, there was a grim Midtown Manhattan pool with sulfuric-yellow water and fearsome denizens of the shattered locker rooms. And then, the fiercely competitive pool at the 92nd Street Y, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, with slow, medium, and fast lanes, where you needed to choose your spot carefully and keep up the pace at risk of getting kicked in the eye.

These days, I drive into Manhattan, drop my car in the Psychiatric Institute’s subbasement garage, and climb seven long flights to the top of the cliff in Washington Heights, where I change into a racing suit and do a hundred or so laps in the pool at the medical student dorm. I swim half a dozen strokes across (it’s a short pool, crammed into the Manhattan grid), turn, and head into the next lap.

In each of these pools, I swim myopically with my fogged-up goggles, tracking the black line at the bottom of the water. I do my half-mile, my mile, whatever the daily quota might be, then get out and stretch. I’m sixty-one now, and the swimmers around me—medical students, nurses, young doctors—are mostly in their mid-twenties. Not that I’m competitive or anything, but I’m faster than most of them, and it takes me fewer strokes to get across the pool. Of course I’ve had decades of practice, trying to make my arms slide smoothly through the water, kicking with the right bend of leg to get the most forward thrust. I can swim a mile in only a few minutes longer than it took me way back in high school, when for a few years, I was on the swim team. With swimming as with writing, it’s all about technique.

I was pretty pleased with my swimming until I went to a high school reunion a few years back. There I met one of my classmates. We compared swimming notes. My mile plus-or-minus in the various pools. His National and Intern ational Masters swimming records, his swim across the English Channel. He told me about swimming the Channel: no wetsuits, only a bathing suit, though it’s OK to grease yourself up. In preparation for the cold North Atlantic waters, he turned down the temperature in his house to the low 50s, ignoring his family’s complaints. I was impressed, a bit jealous. The English Channel! He shrugged: it was nothing. He had a friend who swam the Channel, then, emerging on the other side, jumped back in and swam back. Of that man, he was in awe.

ational Masters swimming records, his swim across the English Channel. He told me about swimming the Channel: no wetsuits, only a bathing suit, though it’s OK to grease yourself up. In preparation for the cold North Atlantic waters, he turned down the temperature in his house to the low 50s, ignoring his family’s complaints. I was impressed, a bit jealous. The English Channel! He shrugged: it was nothing. He had a friend who swam the Channel, then, emerging on the other side, jumped back in and swam back. Of that man, he was in awe.

So, we all do our laps, our lengths, our lines. We work on our technique, our meter, our stroke, our splash, our turns, our special kick, we do our best to move through the medium.

A number of years ago, I interviewed the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks. He told me that he is a swimmer too, and at that time he lived on City Island, a fishing village in the Long Island Sound, part of the Bronx. We compared swimming and writing notes. It was a wonderful afternoon, sitting with Oliver Sacks in his City Island house. It turns out that Sacks has written eloquently about his swimming—in The New Yorker. His father was a championship swimmer. Sacks himself would swim for hours, even all weekend. At times he would circumnavigate City Island, a journey that took several hours. He posits that there is an "essential lightness about swimming, as about all such flowing and, so to speak, musical activities."

Well, yes, that’s true. That is part of it, for certain, the lightness of that flow.

David Hellerstein is a physician and writer in New York. His books include Battles of Life and Death (essays), Loving Touches (novel), A Family of Doctors (memoir), and Heal Your Brain (nonfiction). He has published many essays and stories in the North American Review and has been a contributing editor for NAR for over twenty years.

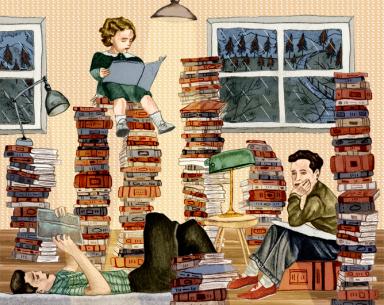

The illustrations are done by Gigi Rose Gray. She is an illustrator born and raised in New York City where she received her BFA in illustration from Parsons New School for Design. She now resides in sunny Los Angeles. Her works are inspired by the grace and elegance of women, mid-century design, french renaissance interiors, the colors olive green and mustard yellow, dreams, cypress trees, Greco-Roman art, and nostalgia.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop