A Strange Collage

My favorite poetic technique of the moment is collage, specifically collage by quotation. I love how collage is so disruptive, so in-your-face. “Look at me, I’m doing work!” a quotation stuck in the middle of a poem suggests. The seams are meant to be seen. It is a thing made, a construction, a mosaic.

I started wondering why I feel so drawn to this practice. Here are some of my ideas:

I am working on a PhD in Creative Writing and Literature. In this capacity, I’m a poet and a scholar. I like to use research from my literature classes in my creative work, which means that at this point, I’m working on collage poems that follow in the tradition of Dickinson, Moore, Carson, and others.

Quotation fractures, too. It creates a moment of instability in the world of the poem. Is the quote ironic? Is it sincere? Does it support what came before it, or disrupt it? I love to happen upon a moment in a poem when a quote suddenly appears, without warning. I especially love when the quote is unattributed, unexplained, or when its validity is unclear, because that is how life is in the 21st century. At least as far as I know it.

But maybe there’s another reason. Maybe I’ve subconsciously joined in a tradition of subversion through quotation. It’s nice to feel like one is an heir to something.

Recently, Mary Beard gave a lecture for the London Review of Books called “The Public Voice of Women,” in which she recounts the familiar moment in The Odyssey when Telemachus dismisses his mother, Penelope, out of the great hall for daring to ask the bard to play a happier song for her suitors. According to Beard, Telemachus’s outburst goes something like this: ‘Mother . . . go back up into your quarters, and take up your own work, the loom and the distaff … speech will be the business of men, all men, and of me most of all; for mine is the power in this household’ [emphasis mine] (Beard).

Beard suggests that western literary tradition is replete with moments of silencing women, of keeping their voices out of public discourse. But what about women who take on the voice of a man through quotation? Did it trouble the tradition when Emily Dickinson, for example, quoted at will from Keats, or Shakespeare, or the Bible?

I must confess: I’ve been reading a lot of Emily Dickinson lately. I’m starting to see everything she did as subversive. Her use of quotation—so varied and strange—does seem, as Susan Howe posited, to be intentionally tongue-in-cheek. Quotation belongs to the realm of scholarship. Scholars were men. Howe writes that 19th century women were meant to listen (My Emily Dickinson 15). Like their children, they were to be seen, not heard.

But Emily Dickinson was a scholar as much as she was a poet. She knew her history, her poetry, her Bible. She quoted directly, but just as often choose not to cite her source. She borrows at will and without permission. Her poem—“I died for Beauty – but was scarce” was apparently composed in response to Keats’s famous line “Beauty is truth, truth beauty” (line 49), but she never directly acknowledges her reference. She simply begins by claiming her allegiance with beauty over truth. Either we get the reference or we don’t. And what’s more, she isn’t actually responding to Keats’s voice in the poem, but to the voice of the urn, who speaks these words to future generations.

To quote on the page suggests an audience. To speak, someone must be listening. Of course, Emily Dickinson had no audience. But she kept on quoting. Or misquoting. Or alluding. Or feigning allusion. She passes over the voice of a great romantic for the voice of a Grecian Urn. She does what she wants.

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote: “It is a familiar expedient of brilliant writers, not less of witty talkers, the device of ascribing their own sentences to an imaginary person, in order to give it weight” (Garber 669). Marianne Moore wrote: “A good stealer is ipso facto a good inventor.”

Employing quotation in poetry is like changing your dress mid-party. The tone has changed. I get to be me, but I get to use an accent. I can speak without consequence. I can make a speech. I can perform the business of men. This is revolutionary poetics. I owe this ability to Emily Dickinson.

What does it mean to take on the voice of another? To put distance between you as the writer and what is being said? To not only absorb but to eat someone else’s words? Quotation to me is a strange kind of collage. I want to believe that it comes out of a long tradition, opened up by Dickinson, of reclaiming a space to speak in the proverbial great hall.

For me, quotation in poetry is intoxicating because it is at once post-modern AND canonical. It makes me glad.

Kay Cosgrove won the Westchester Review's Writers Under 30 contest. She is a doctoral student at the University of Houston. Kay appears in North American Review's issue 299.1, Winter 2013.

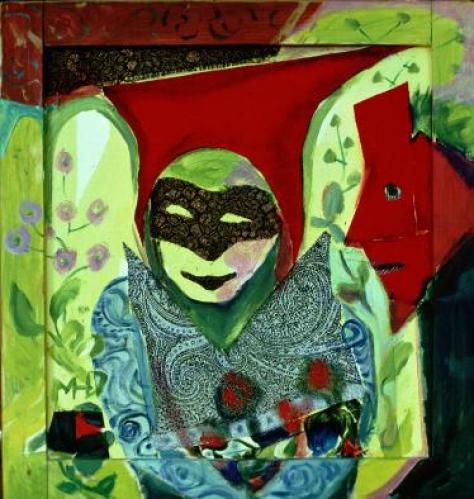

Collage by: Margret Hofheinz-Döring/ Galerie Brigitte Mauch Göppingen

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings