About “The Baker’s Apprentice” from issue 298.1

I wrote the first draft of “The Baker’s Apprentice” when I was nineteen. I thought it was one of the best things I’d ever written, which was true, since I hadn’t written much that was any good at all. I’d been reading a lot of J.M. Coetzee and, in the first draft of “Apprentice,” aped his elegant, restrained style, shaped sentences that were beautiful in a way that resembled the beauty of the author I most admired. A half-conscious method. The task of revision, more than seven years of it, was to sift the traces of that borrowed style, break down the redundancies and flourishes that were among my immature literary habits, and bring out the core of the story, the spine of emotional urgency that, even when I wanted to junk the piece as juvenilia, wouldn’t let me go.

“The Baker’s Apprentice” is a fable about a boy who finds a job as a baker’s assistant and discovers that his idealism about work and women may not be borne out by reality. It’s limited by its austere style, I think, by the archetypal diction of fable; it’s the kind of short story that feels like it wholly contains its world, a world bordered by its language, not a novelistic one that points to human realities that go on and on (so we can imagine) after the story ends. It feels like a story that, perhaps in a problematically self-conscious way, aspires to be “timeless;” a fog hangs over its details of time and place, though such details are there, in the background. It’s not all that grounded in the sensory data of contemporary life, contemporary habits of speech. For these reasons, I suspect, it was rejected by a gazillion magazines over many years.

It’s a story I’m still proud of, though, a story I still think is pretty great. I think it’s pretty great because I find its language inscribed with a kind of existential search—and the vulnerability inherent in that search—that I think is one of the most exciting things to discover in fiction. I’ve lately spun a theory, super provisional, that there are two major modes in which we conceive fiction: there’s fiction as essay, “essay” in the Gallic sense of “attempt”—fiction as the writer’s attempt to unpack a question or experience in literary terms, essentially for her own sake—and fiction as object, as entertainment, intended for consumption by others, fiction that can be sold, that gives pleasure, fiction as it’s conceived by most readers and those whose job it is to sell books, even the most literary-minded among them. The trick is to strike a balance between the two modes: a work of fiction that isn’t the author’s personal clambering towards a truth is unlikely to have much depth or produce language that feels inhabited; a fiction that doesn’t find a pleasing form as an object is unlikely to be enjoyed, or to be read at all.

“The Baker’s Apprentice” was successful as literary essay, as existential attempt, from the very start. The fact that I was so young when I wrote its first draft was a kind of advantage, since my personal search at that time had an adolescent ferocity. It took me seven more years to make the story work as an object, a literary entertainment—to carve it into a form in which it could be published, embraced by others. It took me seven years to make it good enough that I could let it go, as my search lurches on and I try to keep pace and find a new language for it.

Daniel Karasik (b. 1986) is a recent winner of the CBC Literary Award for Fiction, The Malahat Review’s Jack Hodgins Founders’ Award for Fiction, the Canadian Jewish Playwriting Award, and the Toronto Arts Foundation Emerging Artist Award. He is the author of three books: The Crossing Guard & In Full Light, a volume of plays (Playwrights Canada Press), The Remarkable Flight of Marnie McPhee, a play for children (Playwrights Canada Press), and Hungry, a poetry collection (Cormorant Books). His stories and poems have appeared in leading literary periodicals in Canada, the United States, England, and Ghana, including The Malahat Review, The North American Review, Air Canada’s EnRoute Magazine, The New Quarterly, The Fiddlehead, Descant, Per Contra, and Magma, by which they've been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and the National Magazine Award. His plays have been produced across Canada, in the United States, and regularly in translation in Germany.

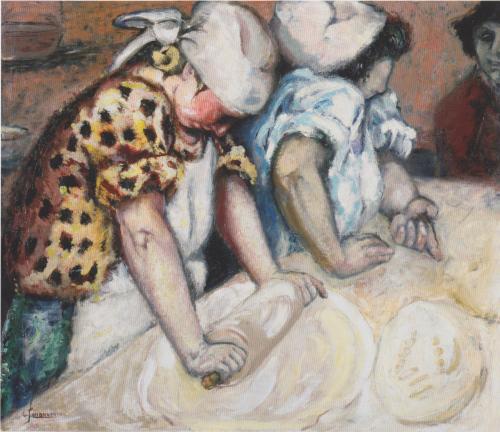

Portrait by Aksel Waldemar Johannessen (1880-1922)

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop