On Bill Knott and "Late Night Song"

Some poems percolate for decades, waiting to be born. My friend and baritone sax player Rick Countryman tells a story about working in a band that played behind an Elvis impersonator. When I heard this story, Rick and I were sharing a tumbledown house in Seattle that had no heat. In the winter, I’d open the stove and stand in front of it for warmth. This was the beginning of the presidencies of Reagan and then G.H.W Bush. Once I remember watching some African-American kids playing hoops. One of them taunted the other, saying, “You’re grandma eats Food Bank Cheese!” and everyone there just broke up in laughter. But not much later, one cold and rainy day, Rick walked through our door with a giant block of the selfsame cheese, and there it stood, Exhibit A of what seemed like an ongoing slide down some invisible chute into the margins of American life, plopped on my kitchen table. Poets can stare out the window and starve. Musicians, though, have the tonic of timeliness and pitch to contend with, so, at least by comparison, they’re more practical-minded. How resourceful, I thought. We were broke, and it seemed like it would always be so, but for a while we ate grilled cheese sandwiches and told each other stories. That’s where the Elvis line came from. In the story, Rick’s cover band had just finished a set, and a fan walked up, pointing to the Elvis impersonator, and said: “He’s one of the best—and brother, I’ve seen a lot of Elvises.” A line that good doesn’t need to be written down.

It only needed a context in which a fragmentary, elliptical, off-the-wall gem of this sort, delivered in earnest, without irony, could be given a home—a native element, and at the time—this is the late ‘80s—there was no better place for that than late night radio. Especially call-in shows. My favorite time of day, of course, was the Open Phone America segment of the old Larry King radio show, broadcast from Washington, D.C. Well before he became a television celebrity, Larry King was an amazing radio personality, making a comeback from a legal dustup of uncertain origin down in Miami, Florida. The first hour featured Larry interviewing a guest—and here, it must be said, Mr. King was at the top of his game. Never mind the image you have of him from TV, the embalmed skeletor in suspenders. He was a terrific interviewer. Then came the magic hour of Open Phone America, when anyone could call in and talk about whatever they wanted. This was when the crazies came out. Numerologists and Psychics and Survivalist Apocalyptic Prophets, the Open Phone hour was like a bright summer porch light in the American darkness to a million circling moths of crazy.

Before the Internet, this was where we all met. One heard the sound of earnestness in those voices, no matter how derailed, no matter how far down the delusional trail they had gone, and Larry was the den father.

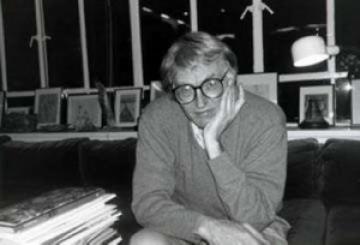

Which brings us to Bill Knott. Swirling in the lamplight of American poetry, he was one of the crazy moths. Before his first book was published, he faked his own suicide then published The Naomi Poems, under a pen name St. Geraud. In truth, you can’t really be a fan of Bill Knott. And being an admirer sounds—and is—false. There’s too much not to admire—or, alternatively, there’s too much Knott to admire. A pattern: he was maker and saboteur—Knott co-authored a novel in 1977 with James Tate, Lucky Darrell, and rumor was that Knott went around to bookstores yanking that book off the shelves. Tate, of course, became, in the poetry world anyway, a superstar. I remember in grad school sitting in a room with John Ashbery and James Tate, and I thought, Here are two giants of our era, an assessment that now sounds a little off pitch. Meanwhile, Knott became the subject of a scattered, invisible, cultish following, whose members, it seemed, wouldn’t fill a freight elevator, but when they discovered each other, would exchange favorite Bill Knott one-liners like trading cards for a superhero whose secret power was a surreal lyric laced with whips and quips, sex and self-laceration, comic and cosmic and petty and ingenious—sometimes shouting, sometimes soft and devastating. He was an orphan. He grew up in an orphanage—that was the source of it all, his true super power. That rage. All his life he was maker and saboteur. His other superhero power was to render any room, any dwelling, any place where he might stay for a time, catastrophically, tornadically uninhabitable. He was a legendary mess. People traded stories about the Bill Knott messes they’d witnessed.

Here’s one: 1980, I saved my money delivering pizzas in Seattle and went to my first writer’s camp—Centrum, near Port Townsend, Washington. Two weeks, surrounded for the first time in my life, with people who all wrote and loved poetry. Daytime workshops. Evening craft lectures or readings. Heaven. You filled out a form stating your top three choices for a workshop instructor. Those choices read like the table of contents to an anthology of late mid-century American poetry: Galway Kinnell, William Stafford, Donald Hall, Lisel Mueller, Meridel LeSuer, Madeline DeFrees, Richard Shelton, and an unfamiliar name: Bill Knott. I wrote down my first two choices: Kinnell and Stafford . . . and then I punted with Knott. I had no idea who he was. On the first day of this, my very first workshop ever, Knott, blonde scraggly hair, bespectacled, schlubby clothes, threw somebody out of the class. Shouted at him to get out, and then we began the work. It was rigorous, my first experience with someone who took my work—our work—more seriously than perhaps I/we did. So, right off the bat we were in love with this strange but deeply serious poet.

Then came his public reading.

Up to that point, poetry readings, in general, could be said to resemble those long pauses you hear in live symphony performances: people coughing, the shuffling of feet, some murmurs—a darkened auditorium, a lectern, a spotlight, a poet rendering his/her poem, an audience sighing with emotive appreciation, a few words of introduction for the next poem, more silence and the sound of pages turning, the poet thumbing through his latest book—Hmmm, which poem to choose?! And were those crickets in the woods outside? No, that was Donald Hall stepping softly through the forest in Birkenstocks before his reading, getting in the mood.

Into all this came Bill Knott, stage right.

At the time, he was trying to quit smoking by using a special cigarette filter, which looked like an extravagant Percy Dovetonsils stage prop—something a Dandy might choose—a Dandy’s fancy cigarette holder. Smoke drifted across the stage, crossed dramatically into the spotlight. He offered no pedantic orienting patter to help “set up” the poem—his “set-up” was part of the poem’s performance. There was no indication about when a poem had come to an end, other than an awkward silence, when Bill Knott would take a pull from his fancy cigarette filter and glare at us. Silence, then nervous laughter. This was theatre of the absurdist stripe. We were not meant to think that the person in front of us, a la Anne Sexton, was about to self-destruct. No, this was self-destruction as a “mask,” as a send-up, a high comic style, stand-up poetry before “stand-up”  became such a hot comedy club genre. This was a character from a Beckett play who had wandered off the set and started a second career as a poet, a career in which the performance, on or off the stage, never seemed to stop. Knott extinguished a cigarette on the bottom of his shoe, and read the poem “Survival of the Fittest Groceries.” He read one-line poems, three-line poems, letting the silences fill the gaps between moments like a sledgehammer: “The only response to a child’s grave,” he intoned, “is to lie down and play dead.” More silence, as the “joke,” hit home, the sledgehammer landing, followed by more laughter, but the audience began to catch on.

became such a hot comedy club genre. This was a character from a Beckett play who had wandered off the set and started a second career as a poet, a career in which the performance, on or off the stage, never seemed to stop. Knott extinguished a cigarette on the bottom of his shoe, and read the poem “Survival of the Fittest Groceries.” He read one-line poems, three-line poems, letting the silences fill the gaps between moments like a sledgehammer: “The only response to a child’s grave,” he intoned, “is to lie down and play dead.” More silence, as the “joke,” hit home, the sledgehammer landing, followed by more laughter, but the audience began to catch on.

It was the opening of a door I hadn’t known existed, a permission given to an intoxicating mode and an aesthetic that I would emulate and adore. Eventually I would distance myself from it, but never fully. To call it surreal was to miss it. It arrived like the crazy message beyond the message of late night radio, of Open Phone America. By the time he was done with us that evening at his “reading,” Bill Knott had everyone in stitches. Poetry meets Beckett meets poetry. None of us in Knott’s workshop could quite say what had happened, but we all understood what was to be done next. Knott fled the scene to his cottage on a hill overlooking the sea. We marched right up to that cottage bearing surrealist gifts and knocked on his door. One of us gave him an orange with a key inserted into it. One of us gave him a shoe. One of us gave him a black bra. He received these gifts graciously and invited us in.

That’s when I saw the mess. Every square foot of floor space was strewn with paper and wads of uncertain provenance. In one corner was a pile of used Q-tips, stained with earwax. I tried not to look in that direction again. He was listening to the B-52s and—this I still can’t quite believe—he was reading our poems for the next day’s workshop. We bubbled and enthused and we talked for a long while about movies. At one point, he reached for a Q-tip and used it—to our great relief—to clean out his cigarette filter. Ah, the filter! Of course. Whew! The next day, he asked me for a ride into town. We drove silently for a mile, and he thanked me and said he’d walk back. And that was the entirety of my personal interaction with the poet Bill Knott.

The third thing about him, more of a fact I learned later than a superhero power, but touching just the same, was that while he was a young poet in Minnesota, walking around wearing T-shirts and army pants, and probably writing The Naomi Poems, Knott was taken under the wing of Robert Bly and James Wright.

I remember not long after that seeing an issue of Ploughshares with a tortured portrait of Knott on the cover, and an interview with him—wherein he spoke of his deep connection to the Italian hermetic poets Giuseppe Ungaretti and Salvatore Quasimodo, and something clicked inside of me. He had reached outside of his own culture and historic moment and made profound connections. So that was how art propagated itself. Back then he was publishing with BOA Editions. I always kept an eye out for him. Later I saw, to my delight, in Outremer, that he was working in form—writing sonnets, of all things. Weird, freaking, head-scratching Bill Knott sonnets. Then a big gap of time, followed by The Unsubscriber, from FSG, which sits on my bookshelf among the other titles of Knott like a row of off-brand tuxedos. Maker and saboteur, by the end of his career, Knott had alienated every publisher of poetry, it seems, and had taken to self-publishing his work—he’d returned to the demos, the great underground substrate of American poetry, the zine, the chapbook—little white booklets, saddle stapled with crayon scrawled titles. I have a stack of them at home that John Marshall of Open Books gave me on a trip back to Seattle. Marshall and I share the same Bill Knott fetish—maybe that’s a bit closer to what I’m after. With a fetish, there’s little choice in the matter. You have it and hold it, and you take it out sometimes, quietly, when you need to. And when I heard of his death in March of 2014, the material for “Late Night Song” finally found its alignment. I knew where the Elvis line would go. It would be something overheard on late night radio, maybe while one was working second shift, or graveyard shift, say, in a hospital corridor. One hears in it, I hope, a quality of rage flashing, even now—perhaps especially now, in this election season of crazy—like what people sometimes call “heat lightning” just beyond the visible horizon of the American demos.

Robin Richardson is the author of Knife Throwing Through Self-Hypnosis, Grunt of the Minotaur, and is working on her latest collection, Sit How You Want. Her work has been shortlisted for the Walrus Poetry Prize, CBC Poetry Award, LemonHound Poetry Prize, and ReLit Award and has won the John B. Santoianni Award the Joan T.Baldwin Award. Her work has appeared in many journals including Tin House, Arc, and Hazlitt of Random House. She holds an MFA in poetry from Sarah Lawrence and resides in Toronto.

Recommended

The Shirt

After Hearing David Rothenberg Sang with Birds

Frothing Pink Poodle Droppings