Concerning "Man in Flower" from issue 300.2

"Man in Flower" was an Honorable Mention in the 2015 James Hearst Poetry Prize contest.

With “Man in Flower,” I was attempting something of an urban pastoral. Yet rather than celebration, I was interested in something more detached, where wild nature could take precedence in a place, the city, which we usually attribute to civilization. However, since detachment is so foreign to how we humans experience the world, I decided the scene needed some form of human presence, but not a living presence, because a living human would ultimately take over the landscape both physically and metaphorically. The man in the poem is dead because death has a way of lifting our veil of illusion when it comes to our place in the natural world.. When we bury bodies, we do not see the equalizing force of decay. Yet, what happens to the man in the poem is exactly what goes on once we are buried in the earth. I wanted to present the man as dissolving organic matter that feeds other organic matter. Ultimately, I am attempting to explore a vision of a connected nature, where nothing is wasted and everything, including human bodies, are transformative matter.

The last layer of metaphor I hoped to get across in the poem was the very fragility of civilization itself. Though it may be the greatest invention of the human species, it is never far from collapsing under the immense weight of all the demands we put on it. Countless civilizations before us  have disappeared, and before their disappearances, the inhabitants of those civilizations felt just as secure, just as indestructible as many of us do today. Therefore, the poem borders on the apocalyptic, but I hope it resists apocalypse because nature once again reclaims the cityscape.

have disappeared, and before their disappearances, the inhabitants of those civilizations felt just as secure, just as indestructible as many of us do today. Therefore, the poem borders on the apocalyptic, but I hope it resists apocalypse because nature once again reclaims the cityscape.

The man might be dead, but everything else continues to live, which is very much something we have forgotten in our mad rush to set wider and wider boundaries between our civilization and the rest of the nature we share the planet with. So, I guess, in the end, I wanted to write a poem of recognition rather than a warning. Warnings seem too human-centric and only end with a fear that moves us to protect ourselves. Recognition, though, offers us so much more than fear. It offers us understanding, and in this particular case, the understanding that polluting and destroying the nature that sustains us is not only foolhardy, but also ungrateful. We have had the privilege to exist on a tiny blue oasis in the middle of frigid airlessness. It has given us oranges, sex, and Paris. It has allowed us sunny stoop and porch days filled with birdsong, and if there’s one thing our probes sent into the abyss of space have communicated back, it’s that nothing of what we have here can be found out there.

We are, as far as we know, stranded on an island, but unlike Crusoe, we do not long for England because there is no England. There is only the island for as far as the mind can fathom. And here we remain blissfully ignorant of how truly rare we really are.

The man lies in the tall grass by the old railroad yard.

No one walks this way anymore, it’s moon-filled

and sun-stilled. Trains haven’t run here since before

the bicentennial. Weedy trees rise up around the man

like a jungle, or barley waiting for the farmer’s scythe.

A white flower has burrowed its way through his temple,

blossoming from his bottom eye. He is man with flower

now/man-flower. Above him, in the ratty leaves

of an ash, starlings have made a noisy nest. Each day,

they speckle him. Seeds also gather, stubby sprouts

already rising from his thin jacket, his faded jeans,

the loose skin of his face. His body will be safe

for a while. But once covered in grass, in the heaviness

of daisies, everything the man is will shrink, flatten out,

until what remains is a field where no one ever goes.

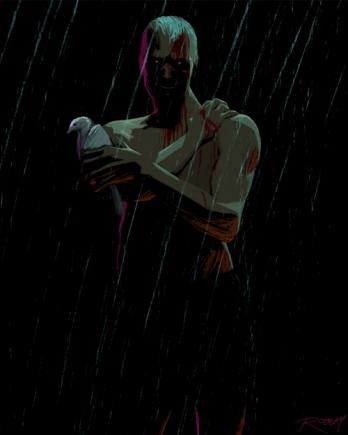

Illustrations by Clay Rodery, an illustrator who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Clay’s illustrations have been featured in the North American Review issues 298.4, 299.1, 299.3 and the most recently is issue 299.4, Fall 2014 and 300.2, Spring 2015.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop