Divine Decay: The Scent of Old Pages

My copy of The Divine Comedy smells as good as it did when I acquired it decades ago. Previous owners’ comments embroider the lines, punctuated with exclamation points and question marks, stars and circles, lines and arrows. The pages, dry as fall leaves (of course), are a darker brown around the perimeter, a reverse halo, circumnavigating the terza rima stanzas that to this day reek of Dorothy L. Sayers.

This stack of Penguin Classics sits on my desk, fragrant, ripe, a bouquet of paper, ink, and glue: Dante, The Divine Comedy; Robert Graves’s The Greek Myths (Volume I); Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars; and Montaigne’s Essays. I give each the sniff test, which results in a sneezing fit: good snuff, but I have to admit that the copies of the Graves and Suetonius might need more time to ferment, while the Comedy and the Essays each has a distinctly evolved nose, coupled with a bold yet complex finish, their paper brittle, their glue hard and cracked, requiring that their spines be cossetted in Scotch tape, which itself is now withered to a Miss Havisham pallor ("So!" she said, without being startled or surprised; "the days have worn away, have they?"). Yet the composition in these books seems augmented by such physical decomposition.

In May 1948, Dorothy L. Sayers completed her sixty-six-page introduction to the Comedy with advice both practical and divine:

The ideal way of reading The Divine Comedy would be to start at the first line and go straight through to the end, surrendering to the vigour of the story-telling and the swift movement of the verse, and not bothering about any historical allusions or theological explanations which do not occur in the text itself. That is how Dante himself tackles his subject. His opening words plunge us abruptly into the middle of a situation:

Midway this way of life we’re bound upon

I woke to find myself in a dark wood,

Where the right road was wholly lost and gone.

In this edition of hell, the poem exceeds 200 pages and is laden with “Commentaries,” where, at the conclusion of each canto, the images are examined from cultural, historical, and religious perspectives. More baggage than Ulysses, perhaps, but ultimately necessary, or at least useful, and all too often so intricate and engaging that it’s hard to tear yourself away from the miniscule font and begin the next canto. Meanwhile, previous readers’ marginalia provide layers of interpretation, earnest, if at times imperfect: “A civilization in which treatchery [sic] and fraud prevails [sic] is in a state of sickness and decay” (Canto XXIX, 257).

But an old book provides tacit reassurances, developing over time the same ancient charisma we find in Santa Maria del Fiore, more appealing for its patina of antiquity. Erosion caused by readers’ fingers enhances this copy of the Comedy, just as centuries of tourists climbing the narrow stairs inside the Duomo have left the steps worn, chipped, and cupped. I doubt that my four Penguin Classics qualify as rare books—for that distinction they would have to go back even further; they would need hard covers and perhaps marbled or gilt endpapers. It might also help if their subject matter were also considered, if not rare, esoteric or, better, obscure. You can find a copy of The Divine Comedy almost anywhere. You can Google it, certainly, though it’s not the same—doesn’t look the same, and certainly doesn’t smell the same.

I believe I may own one “rare” book: Boston, Its Byways & Highways: Being Twenty-Five Drawings Reproduced in Photogravure, by John Albert Seaford, published by LeRoy Phillips, Boston, and T. N. Foulis, Edinburgh and London. There is no publication date, but the University of Michigan Library catalogue entry guesstimates “1916?” It’s a book to be handled with care, so fragile, so vulnerable that you’re mindful of how you turn each page. And the smell! I grew up in a Victorian house outside of Boston and this book smells exactly like the wallpaper in my third floor bedroom. It wasn’t necessary to put your nose to the wallpaper to smell it—though I did so on numerous occasions—because the musty odor of dry glue and curling paper was part of the room’s slant-ceiling atmosphere. The colors of Boston, too, are reminiscent of the wallpaper, all variations on brown. When I was a boy, the recurrent images in this wallpaper were mesmerizing and hypnotic; if you stared at it long enough the pattern would, like Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s yellow wallpaper, become invitingly, horrifically three-dimensional. Though I didn’t realize it as a boy, the wallpaper presented rather common Victorian depictions of Roman themes: gardens and vineyards in a profusion of abundant decay, broken and toppled stone arches and marble columns, men lounging in togas and Dante-esque laurel wreaths, and lyre-strumming women draped in loose-fitting yet suggestively clingy gowns.

With one whiff, Boston, the book, brings all that back. Each of the twenty-five drawings are reproductions of pen and ink renditions of Boston’s streets and buildings in the early 20th century—some have long since been sacrificed to the early 60s urban renewal movement called the New Boston, while other locations still look very much the same today. On the book’s cover, Bulfinch’s Massachusetts State House is viewed from the Common where it borders Park Street. There are portraits of the Cambridge Bridge towers (often referred to as the Pepper Pot Bridge), The Shaw Memorial on Beacon Street, Paul Revere’s house in the North End, and Trinity Church overlooking Copley Square. Other drawings depict the construction of the Custom House Tower (completed in 1915, so the book must have been published after that date), which still stands. My father’s business was on Canal Street, a block from North Station which housed Boston Garden (which itself has been replaced); during and after my student days at Boston College, I lived and worked in various neighborhoods in the city. Thus I miss the old Boston, which makes this book all the more important to me; its series of sketches of public places are eloquent, understated, yet intimate, and I don’t have anything else that smells like my old room.

Nothing lasts, though old books, and the people who love them, are putting up a valiant fight. With the advent of e-books and other hi-tech barbarities, the battle will only intensify. Recently Florida Polytechnic University opened the first “library” that does not house any books. This is progress, some might argue, but I find it disconcerting (call it something other than a library), and trust it will only motivate book hoarders to obtain and preserve old and even rare tomes, hiding them away in what will one day be considered literary catacombs.

Nothing lasts, though old books, and the people who love them, are putting up a valiant fight. With the advent of e-books and other hi-tech barbarities, the battle will only intensify. Recently Florida Polytechnic University opened the first “library” that does not house any books. This is progress, some might argue, but I find it disconcerting (call it something other than a library), and trust it will only motivate book hoarders to obtain and preserve old and even rare tomes, hiding them away in what will one day be considered literary catacombs.

I recently read (online) about how reading an e-book can be a rather sterile experience, because an iPad or Kindle doesn’t smell like a book. This has led to a practical, if vicarious, solution: you can now purchase air sprays, candles, and even perfumes that provide a rich blend of paper, ink, and glue to the atmosphere while you peruse your e-book. For instance, on Amazon (of course) you can buy an “Ex Libris” scented candle for forty-seven dollars. But if you really like that old book smell, couldn't you just spend forty-seven bucks on a stack of old books?

John Smolens has published nine works of fiction, including Quarantine, The Schoolmaster s Daughter, The Anarchist, The Invisible World, and Cold. He is a professor of English at Northern Michigan University. His story, “Geography at the End of the World” is featured in issue 298.1.

Painting by Domenico Di Michelino (1417-1497)

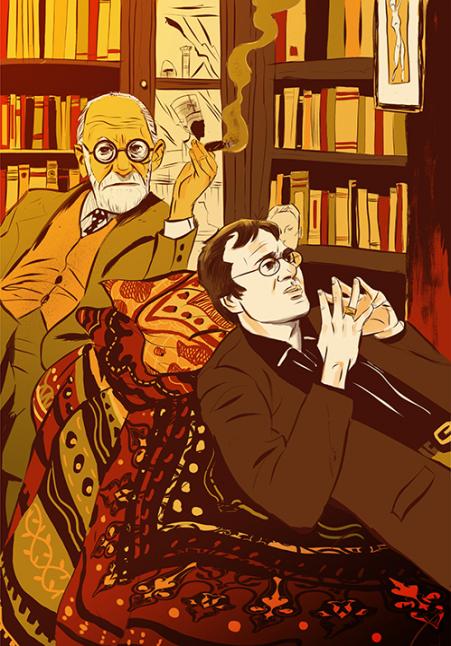

Illustration by: Ryan Inzana. Ryan is an illustrator and comic artist whose work has appeared in numerous magazines, ad campaigns, books and various other media all over the world. His graphic novel Ichiro was the honor selection for the Asian/Pacific American award for young adult literature and was also nominated for an Eisner. You can see more of his work at www.ryaninzana.com. Inzana's paperback edition of his award winning graphic novel Ichiro releases on November 4th, 2014. You can find it in your local bookstore, comic shop and/or online: www.hmhco.com/shop/books/Ichiro/9780547617893# or http://www.amazon.com/Ichiro-Ryan-Inzana/dp/0547617895/ref=sr_1_1_twi_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1412774904&sr=8-1&keywords=ichiro.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop