Every Atom | No. 115

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

Whitman’s disappearing perfumes visit this morning as they do nearly every week; they are right up there with Proust’s madeleine for favorite scents in literature. I have turned on the diffuser my grandson Finn gave me for Christmas: light, nourishing mist fills the room with eucalyptus, clove, citrus, and lavender.

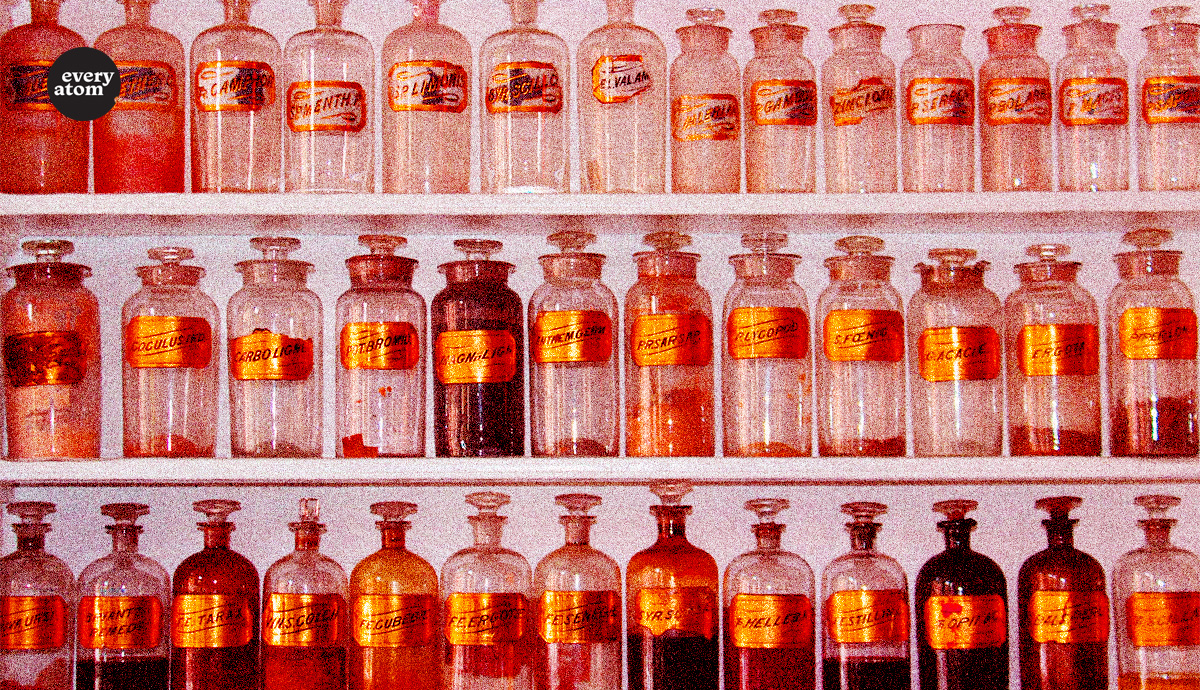

I read the stresses of the first portion this way: Hóuses and róoms are fúll of perfúmes—four stresses, a nimble hybrid of iambic-anapestic measures heard throughout the great poem, the loping biblical sound that seems to come unadorned from the middle of the King James versions of Hebrew texts. This enchanting phrase comes with loose category assignments: Houses and rooms—are they separate categories? There are many other such moments in literature: Wordsworth’s Rolled round in earth’s diurnal course/With rocks, and stones, and trees (“A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal”) and Dickinson’s: A Quartz contentment, like a stone. Such noun pairs propose independent status for the units even as one noun seems to absorb the other. Whitman’s houses and their rooms—or rooms outside of the houses—are full of these scents. The fascinating lexicon on “Song of Myself” assembled by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp comments on the word “distillation”: “This is the first of many instances of his love of the terms of art from nineteenth century American trades and crafts.”

The word “perfume” comes from an Indo-European root word, “dheu”; according to Calvin Watkins’ guide, it means “to rise in a cloud as dust, vapor or smoke”; the emphasis is on rising rather than on any distinctive smell. The poet goes on to say he likes these concentrations but is concerned about their intensity: will the essences will intoxicate him? It is as if he needs the diffuser of other air to provide a matrix for this experience of inwardness. This second stanza isn’t so much an appeal to a specific outdoor atmosphere as it is a summoning of a different state of being, a more immediate physical state of being outdoors, with the scent distributed; the poet desires a naked way of being that takes one’s self-consciousness and interiority to a larger atmosphere. It’s fascinating that Whitman used so many ellipses in his 1855 edition…. Here they seem like droplets of perfumes. The poet does not reject the inward fragrance of the houses; he seems to “know it and like it,” but he needs to go outside to be complete.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop