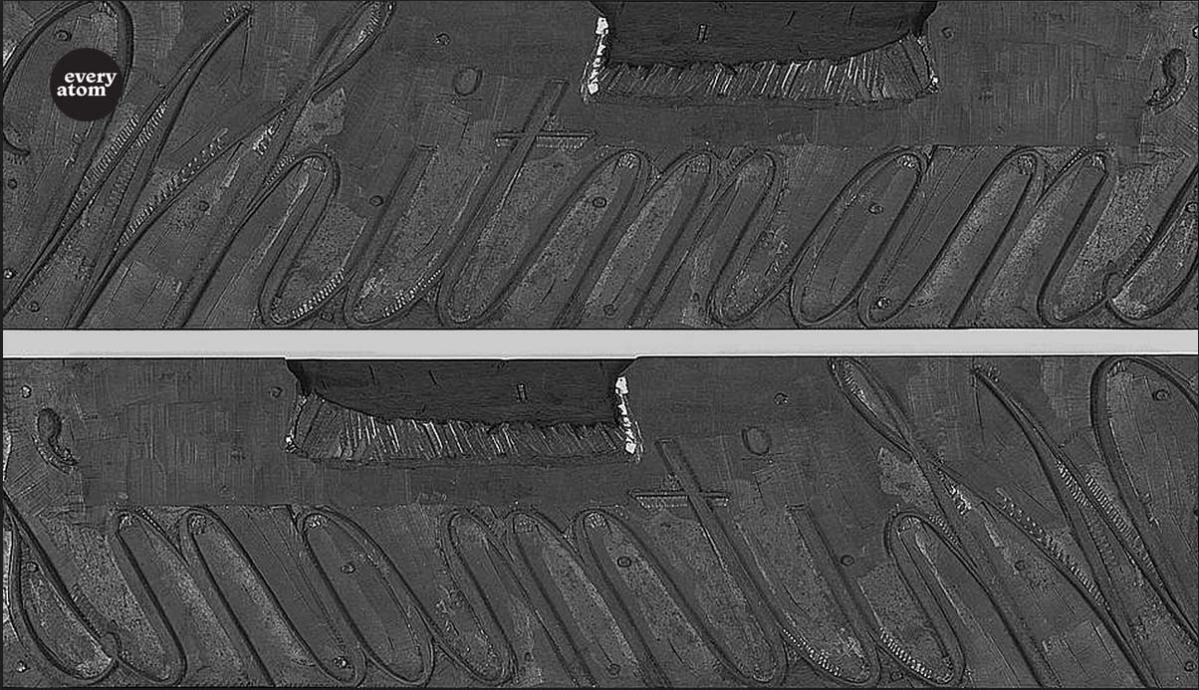

Every Atom | No. 127

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

I want to dwell on this line, without hastening on to the “twirl of the tongue” that follows it. “My voice goes after what my eyes cannot reach.” Whitman explains that the identities and experiences he draws into his song go beyond the horizon of what he could know. Unmoored from a traditional self, he becomes a voyager, his voice audaciously pursuing others like a lover, hunter, or follower of new gods. The hounded slave, the mashed fireman, the suddenly widowed wife, the Arctic sailor, the condemned mother, the madman gripping a knife, the song assumes them all.

Two hundred years after Whitman’s birth, it is easy to imagine the line as a confession, an apology extended to an insulted world. “I am sorry that my voice claimed identities that were not my own,” the chastened poet might say in trying to quiet a Twitter storm. The line tells us that, in 1855, Whitman believed that visionary realism was rooted in voice rather than witness. His song imagines, encompasses, and crowds other people’s talk. People have accused Whitman of democratic privilege, imperial sympathy, and a dozen other encroachments. But such offenses do not tally in his song. He keeps flying the flight of “the fluid and swallowing soul.”

I often think of this line when I read “Dedications,” the concluding poem to Adrienne Rich’s “An Atlas of the Difficult World.” Rich describes multiple scenarios in which others might be reading her work.

I know you are reading this poem

late, before leaving your office.

I know you are reading this poem in a waiting-room

of eyes met and unmeeting, of identity with strangers.

I know you are reading this poem as you pace beside the stove

warming milk, a crying child on your shoulder.

Rich shares Whitman’s desire to imagine the poem’s presence in other people’s lives, but her atlas presumes discrete identities living in their own space and time. As Rich knows, the strangers in that waiting room will ultimately remain strange and unknown. There are no sins of appropriation in Whitman’s aesthetic world. There is only a voice commanding us to merge.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop