Every Atom | No. 131

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

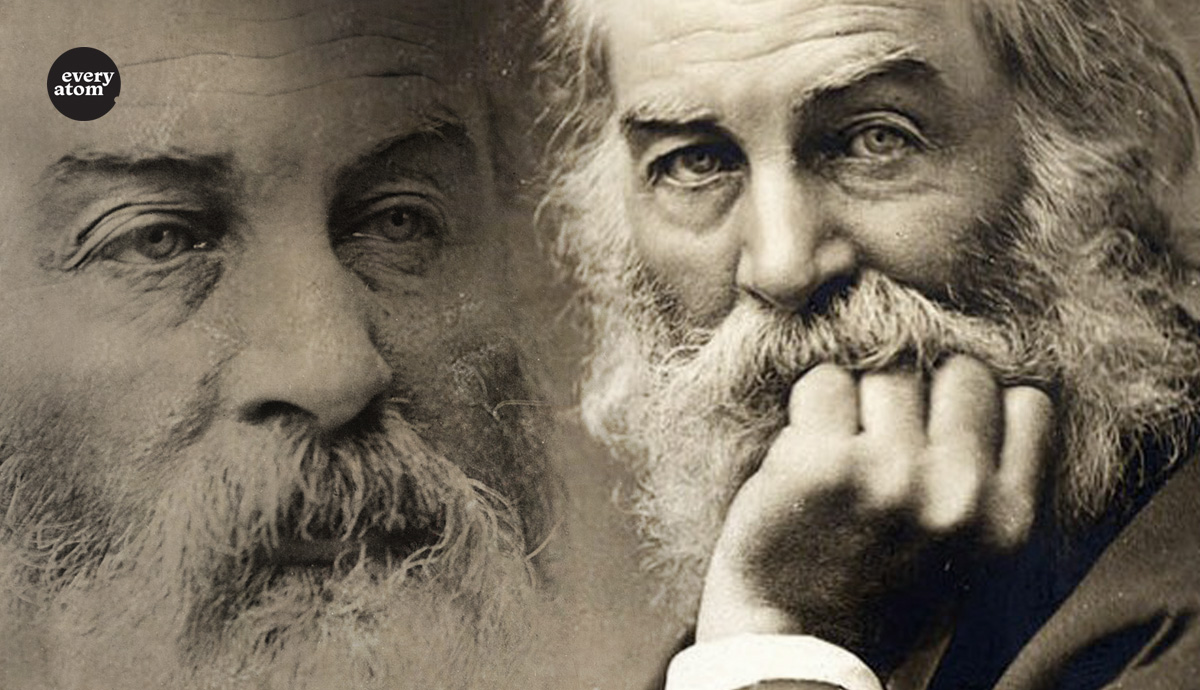

Inside the Seaport Museum in lower Manhattan, Sergey Gandlevsky and I strolled through the special exhibit of Whitmaniana. We gazed at the worn first edition of Leaves of Grass as if it were a leather icon of the Theotokos. On the 150th anniversary of arguably the most important book of American poetry, no one was there to elbow past to get a better look at this talisman. A solitary guard dozed in a chair in the corner. The first edition, self-published and authored anonymously, was the great humus that Whitman would cultivate over the course of his life, and which mothered so many other poets.

Gandlevsky—recently named Russia’s most important living poet—gestured to the snoozer, whose legs are now twitching in a dream.

“He’s only pretending to sleep,” he said in Russian, “so that he can trick us into trying to steal this treasure.”

In the United States, what Whitman called “the greatest poem,” let’s face it: poets are considered weirdos, losers, nutjobs—the detritus of capitalism and its brawny skyscraping successes. In Russia, poets become museums, monuments, the names of subway stops, streets, and even whole cities. There are not one, but several towns named after the great poet Alexander Pushkin, the wooly-headed descendant of an African slave.

All over Russia, in Yasnaya Polyana, in Petersburg, in Moscow, in Peredelkino, I leaned in to hear the hushed tones of docents in the house-museums of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and Akhmatova and Pasternak—as if the writer were in the next room immersed in their next opus, and we, the persons from Porlock or East Jesus, were blundering through, in danger of destroying the delicate translation of Muse to Writer.

Gandlevsky had a small legion of admirers, who reported sightings of him riding the Metro in Moscow—as if they were suddenly entering the frame of his poems. Isn’t that the sign of a true poet—that they change the way we see the world, because their imagination has been written into reality?

Here in the States, in the odd quiet of a lower Manhattan afternoon, we could only imagine the teeming crowds that Whitman lusted among, and wished to be part of. In the last room of the museum, we approached a pair of the poet’s black boots in a glass box—one standing, one leaning, like two leather loaves, like the final section of “Song of Myself”: “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, / If you want me again, look for me under your boot-soles.” I wondered who among Whitman’s admirers saved his boots, as if he were a saint and this were an artifact vibrating with his holy presence?

I lifted my camera and look around to make sure the coast is clear, since photographs were forbidden. Whitman himself wrote “[I’m] not contained between my hat and boots.” Officer, I planned to say, I was taking a picture of absence, to remind myself of what I could never know.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop