Every Atom | No. 150

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

Immense have been the preparations for me,

Faithful and friendly the arms that have helped me.

Cycles ferried my cradle, rowing and rowing like cheerful boatmen;

For room to me stars kept aside in their own rings,

They sent influences to look after what was to hold me.

Before I was born out of my mother generations guided me,

My embryo has never been torpid…. nothing could overlay it;

Monstrous sauroids transported it in their mouths and deposited it with care.

All forces have been steadily employed to complete and delight me,

Now I stand on this spot with my soul.

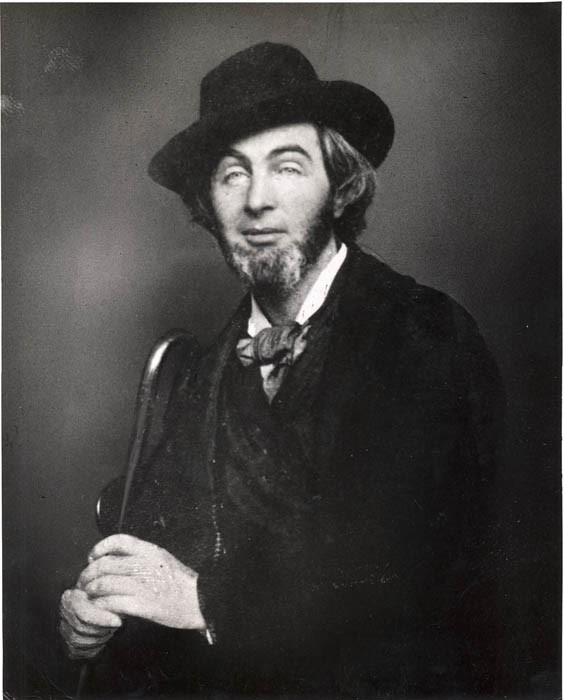

I do not feel any kinship to my ancient relative, Walt Whitman.

Granted, the man died a century before I was born, and so many generations have passed—you’d need to go back to grandfather’s grandfathers, and maybe even theirs, to find anybody who knew him personally—and heaven knows he’s never once come to a single one of my dinner parties. But I have some of his things and, I’m told, even a passing, marginal resemblance, especially in my misspent youth when I was, like him, a scruffy ragamuffin, full of pomp but lacking posture.

I am, to Whitman, doubtlessly a disappointing relation. But I, a former schoolteacher, sometimes journalist, sometimes warrior, sometimes poet, get to live a life very much among his real descendants. After all, I’ve spent the last three years going around the country, starting from fish-shaped Paumanok where we were born, on a delightful series of wanderjahrs to make conceptual portraits of most of America’s most notable poets.

But in spite of proofs, and figures, ranged in columns before me, and charts, and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them, all telling me that I must, am blood-bound to wrap myself in the cloak of America’s bard, I do not feel it. Whenever interviewers excitedly ask me about him as if I’d just married the man last week, I tell them over their audible frowns that I’m here to talk about all the living poets I’ve met and treasured and adopted as family, and move on.

The Abenaki poet Joseph Bruchac wrote a poem called “Prints” which I’ll not reproduce, but rather summarize: Bruchac talks about the unique similarity between old family photographs and fingerprints. You may have them all your life; you may see them every day, though not regard them; you’ll see patterns and swirls and distant, fogged faces from the past, but see no resemblance, until one day a stranger—a detective or a friend—looks at one or the other with their fresh eyes and says hey—that’s you.

We are who we were.

That said, though I protest that he never crosses my mind, he does. Often, when traveling for this and other projects, I’ll sleep out under the stars. I’ll spend the evening looking up at them, in perfect silence, thinking about the very people that Walt talks about in Song of Myself: our parents born here, of parents the same, who were formed from the island soil as he and I, who looked up at those same stars as he and I. I have a number of photographs of them, and him, and others, in old tintypes on my living room wall, liberated from grandmother’s old family albums, and covered in two centuries worth of oily fingerprints.

For the first couple years of this project, I mostly tried to avoid references to Walter; nobody wants to stand in a shadow, and I have felt—then, and now, and always—that the poets of America today, living poetry and breathing poetry and loving poetry and dying poetry, carry in their lungs and blood and genitals far more atoms of Walt Whitman than I ever have, or will, or could. But in my case, it all comes down to timing: around the time the book started coming together, I signed up for an Ancestry DNA test. They sent me a little cup that I had to spit into to a truly disgusting degree—a vile and unfortunate souvenir of myself—with instructions to then render it unto an unsuspecting mailman, who would hand my polymer spittoon to a further series of mailmen, who eventually delivered it to a waiting Mormon lab technician. The very day I signed the book contract, weeks later, the gene results came in: there, preserved for the internet forever, were my living DNA matches, in love seeded within me across two centuries: people named Whitman, and Van Velsor (his mother), Brush, and Platt (his grandmother and great,) a group of far-flung, familiar strangers as numerous as the stars.

In the end, perhaps, it was necessary that some scientist in Salt Lake City take a look at me, take a look at him, and say, no matter how much I might protest:

Hey. That’s you.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop