Every Atom | No. 167

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

When I first read these lines around age 23 or 24, they felt like permission. To be in paradox. To let the self and the mind alter course. To not develop a life according to how other people want to see you and keep you in line. Whitman refused to keep anything in line.

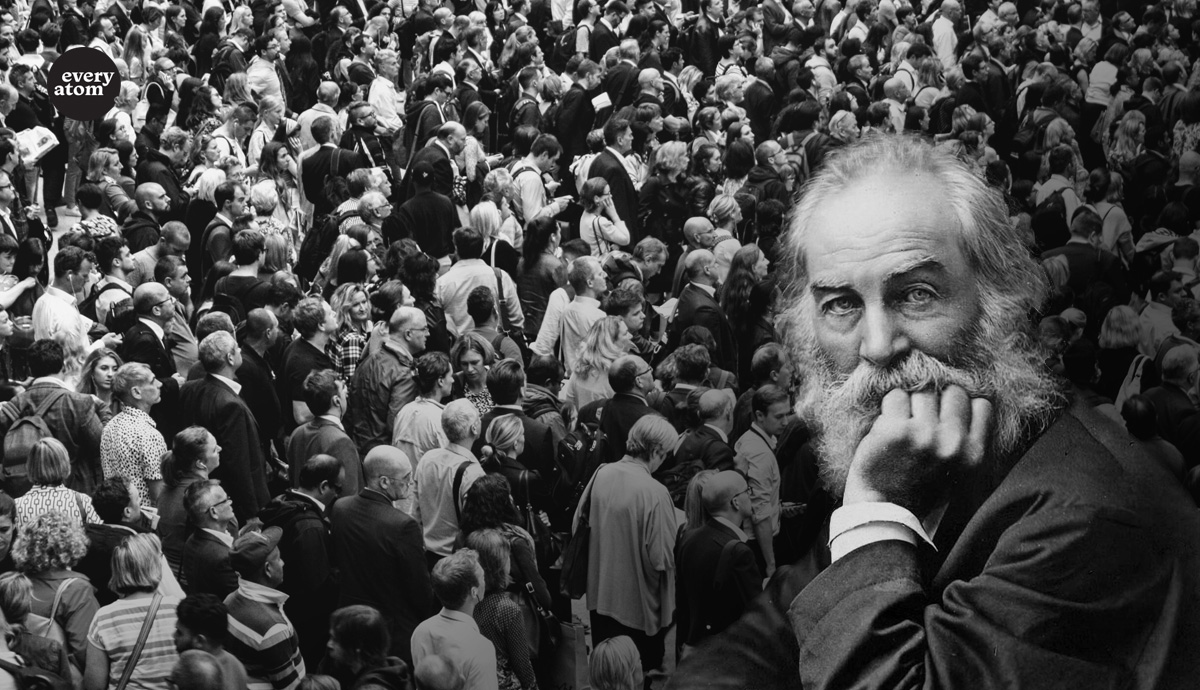

Years later, I read them with more appreciation for Whitman’s fullness as poet and human being. That last statement—“I contain multitudes”—says in three words Whitman’s poetics and philosophy of life. Every time I open Leaves of Grass, I'm left breathless with just how much he availed himself to, received, contained. The voices of prostitutes and forgotten women, of slaves being sold, of naked swimming men, soldiers, children, the diseased, the Mexican native, “the negro from Africa,” the body electric in all its radiance and on and on and on. From opera critic to poet to soldier’s nurse, he did contain multitudes.

To read Whitman in the early 21st century still leaves me breathless. Breathless with hope. For Whitman remains one of the ultimate yes-poets, poets that insist upon affirming the full range of experience and this tenuous existence, who somehow can critique and dissolve criticism at the same time with celebration. He is a poet cataloguing wonder in every verse, insisting that radical openness with porous borders marks the promise for this democratic experiment of the United States and for this biological experiment of humanity.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop