Every Atom | No. 187

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

How would Whitman have composed “Song of Myself” with thought of the mandate to which he will later give voice in his remarkable 1871 essay, Democratic Vistas—namely, America’s need to forge a literature that breaks completely with its cultural past and ushers in a revolutionary new cultural and political epoch? I would expect Whitman to write with a sense of the sheer originality of his verse. And I would expect he would not trust a culturally underdeveloped America to grasp the democratic lessons his poem sets out to teach. So he would assist readers with insight into the meaning of “Song of Myself” and, perhaps, subsequent to its publication and reception, direct readers to his having done just that, as he did in Democratic Vistas: “Books are to be call’d for, and supplied, on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half sleep, but, in highest sense, an exercise, a gymnast’s struggle; that the reader is to do something for himself, must be on the alert, must himself or herself construct indeed the poem, argument, history, metaphysical essay —the text furnishing the hints, the clue, the start or frame-work.” If Whitman’s “Song of Myself” furnishes the hints, the clue, the start, or framework for readers to construct its interpretation, such assistance may be the original concluding line of the verse later numbered #15:

And such as it is to be of these more or less I am.

With this line Whitman signals the creative act defining his “Song,” actually plural acts of self-creation through which he creates his identity, “more or less,” from all “these” he lists. Whitman’s list assembles nearly a hundred personas: the prostitute and the President, the first child and the Patriarchs, the marksman and the Flatboatmen, the pure contralto and the conductor, the lunatic and the opium-eater, young and old husbands and wives, the living and the dead. As Whitman’s line explains, his acts of self-creation are acts of imitation of all “these” he lists and includes throughout the whole of his great poem. His “Song” reminds us of this often. “In all people I see myself—none more, and not one a barleycorn less.” “Whatever interests the rest interests me.” Pondering the fate of an escaped slave, he tells us, “I am the hounded slave, I wince at the bite of the dogs.” Of a soldier he says, “I do not ask the wounded person how he feels—I myself become the wounded person.”

“To be of these more or less” Whitman means; he not only feels, but, as he declares—“I am.” Throughout his “Song” he strives through imitation to create that “great composite democratic individual, male or female” whom he revealed in the Preface of 1872 to As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free was one of the lyrical intentions of Leaves of Grass. Whitman imitates all “these” who are different to become different himself. And if his 1855 readers missed this in his original concluding line to Verse 15, his Song’s final version adds an astonishing line that again “furnishes the hints, the clue, the start or frame-work” for grasping his poem’s meaning, which his new concluding line ties to its very title:

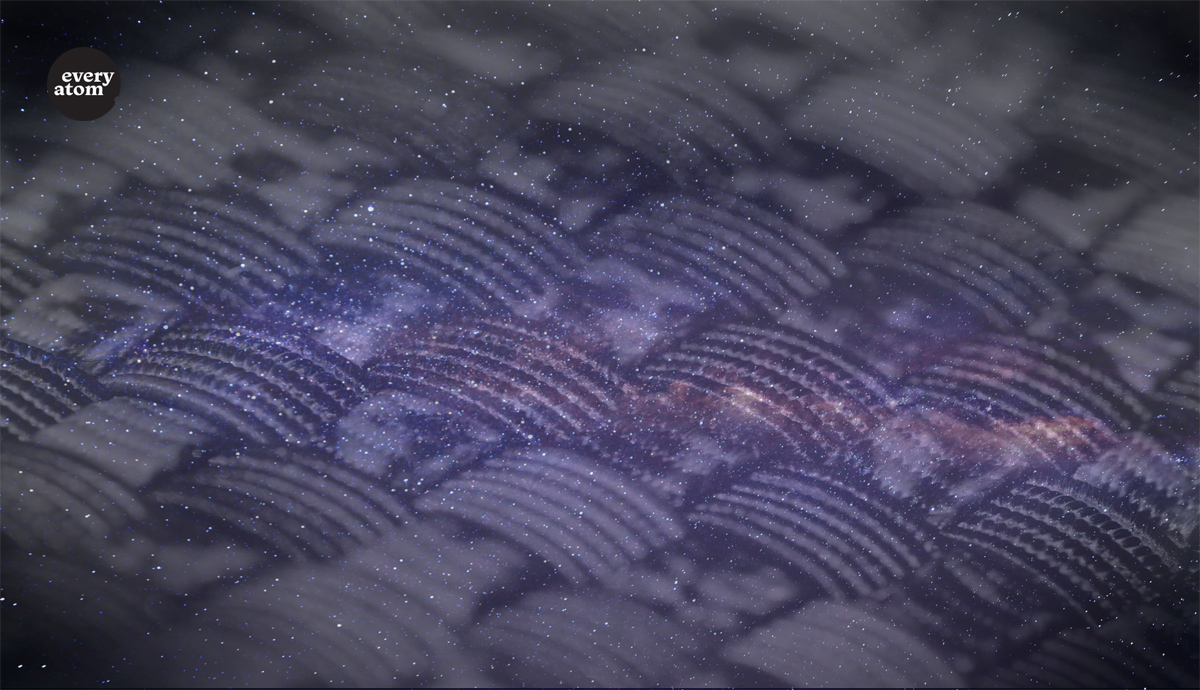

And of these one and all I weave the song of myself.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop