Every Atom | No. 47

Introduction to Every Atom by project coordinator Brian Clements

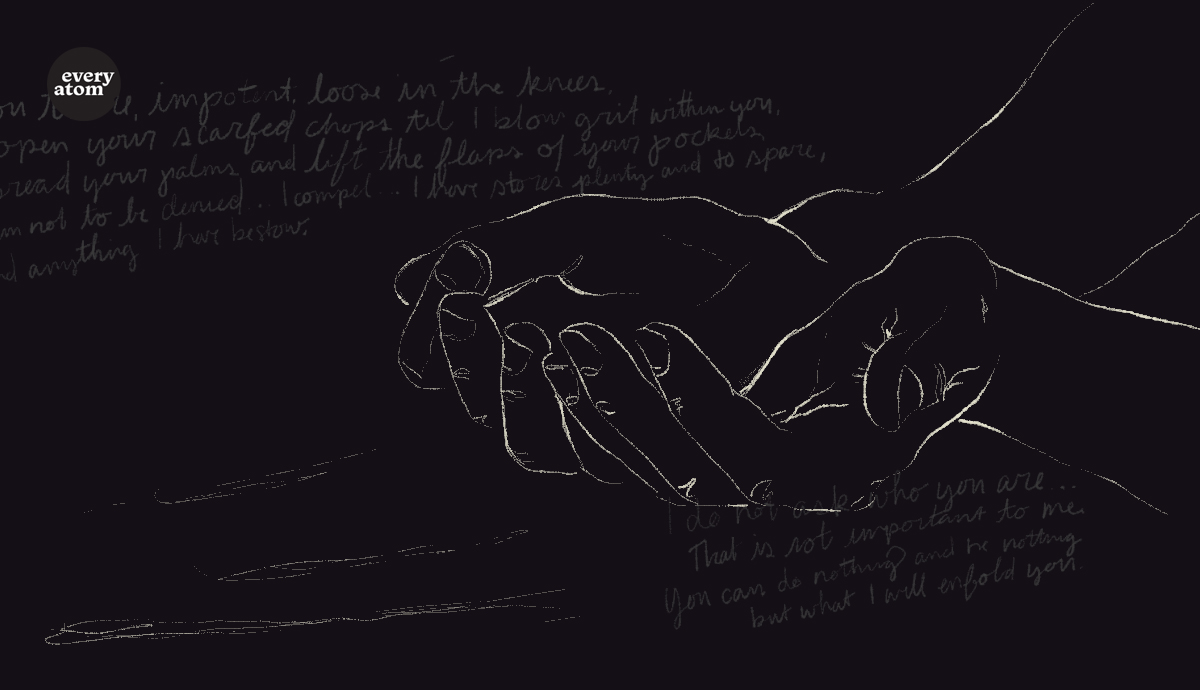

You there, impotent, loose in the knees, open your scarfed chops till I blow grit within you,

Spread your palms and lift the flaps of your pockets,

I am not to be denied....I compel....I have stories plenty and to spare,

I do not ask who you are....that is not important to me,

You can do nothing and be nothing but what I will infold you.

At the outset of his long poem, Whitman introduces into poetry in English a new forceful attitude toward the imagined figure of the reader. The reader “shall assume” only what the poet assumes, thus the reader’s mind is invaded and overturned in the opening lines. Next, his bodily existence is denied its sovereignty, for the reader and the poet share the same “atoms”; they are made of the same stuff. The reader, in this dance where Whitman leads, is not so much instructed and delighted as neutralized and overwhelmed.

The passage I selected is one of many in which the reader is enveloped by Whitman’s daring claims on him. Here, well past the poem’s half-way point, Whitman seems to call out to the reader as if in a crowd or across a street. No more “dear reader.” “You there,” the poet shouts, grabbing the reader’s attention only to deliver insults (“impotent, loose in the knees”) and issue commands worthy of a drug bust: open your mouth, spread your hands, show me what’s in your pockets. Of course, Whitman can be tender too, even seductive, and sometimes simply hospitable; he often “invites” the reader. But what I am highlighting is Whitman’s more assertive voice. This poet will not dispense a lecture or commit acts of charity. The trumpeting power of Whitman’s will is “not to be denied.” The poet claims to give all of himself, not as a donor would to an individual (“who you are…is not important to me”) but as someone who overcomes and “infolds” his subject. The reader at various points in “Song of Myself” is elevated, whispered to, and reassured—the reader may even feel Whitman’s hand on his shoulder—but here and throughout, the reader is handled so forcefully as to be enveloped and subsumed. I know no poet writing before or after Whitman who has dominated the reader with such a powerful love.

In a time when the content of poetry is increasingly broadcasted to a general audience and acted out on a public stage, Whitman reminds us of the rhetorical force and intimacy that can occur when the poet is alone with an isolated reader.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop