Every Atom | No. 65

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

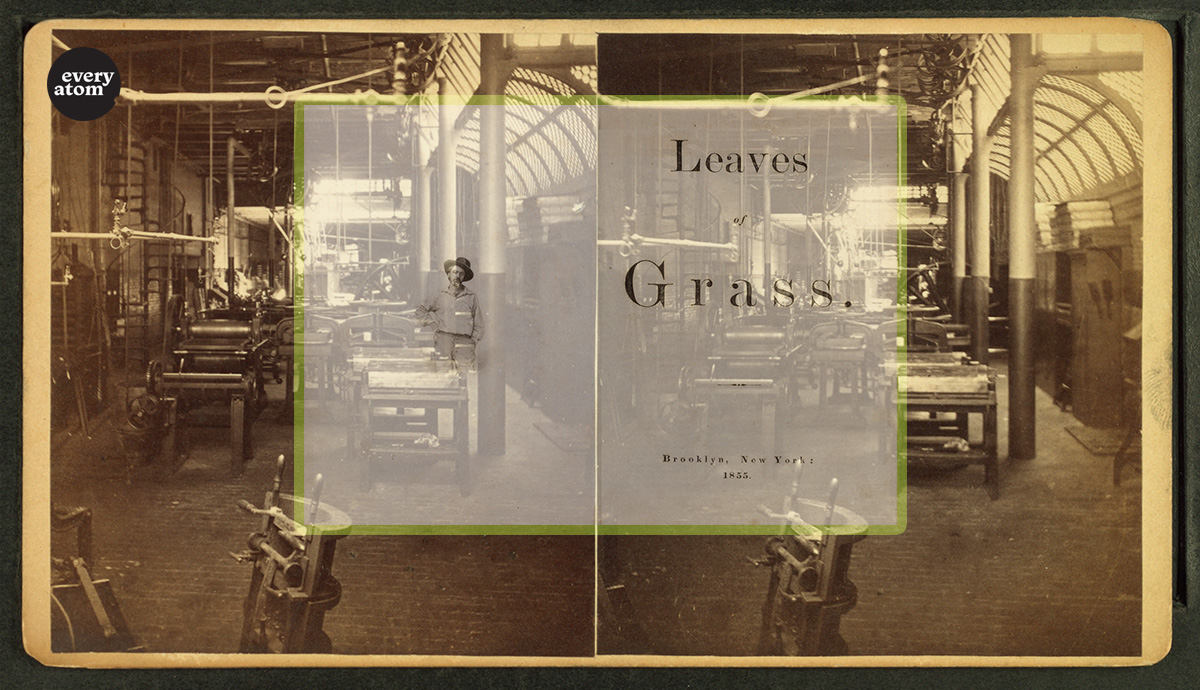

In a manuscript note from the late 1850s, Whitman identified his mission to be “The Great Construction of the New Bible,” and in the 1871 poem “Passage to India” he dreamed of traveling to “realms of budding bibles.” In an under-examined passage of “Song of Myself,” Whitman fulfilled his promise from the 1855 preface to Leaves of Grass indicating that “America does not repel the past or what it has produced under its forms or amid other politics or the idea of castes or the old religions” by describing his new American bible as the accumulated pages from the “budding bibles” of the past:

Taking myself the exact dimensions of Jehovah and laying them away,

Lithographing Kronos, Zeus his son, and Hercules his grandson,

Buying drafts of Osiris and Isis and Belus and Brahma and Adonai

In my portfolio placing Manito loose, and Allah on a leaf, and the crucifix engraved,

With Odin, and the hideous-faced Mexitli, and all idols and images.

When Whitman writes in the first line of this passage that he is “Taking myself the exact dimensions of Jehovah,” he seems again to identify himself as a modern poet-god whose goal is to replace the deities of the past. As the following lines indicate, however, Whitman is not taking Jehovah’s measurements in order to assume his divine garb. Instead, Whitman is measuring the size of a page of sacred text upon which Jehovah is described so that he might tip this page into the binding of his new American bible. In addition to this page devoted to the Israelite god, Whitman includes lithographed images from the sacred narratives of ancient Greece, drafts of pages that contain the gods of Egypt, Assyria, and India, loose sheaves of paper for the Algonquian and Islamic deities, an engraving of the Christian cross, and portfolio pages of gods from the Norse and Aztec traditions. Whitman’s new bible does not rise from the ashes of old bibles that are burned away in the consuming fire of modernity. Rather, Leaves of Grass is a composite of the leaves from older bibles. While elsewhere Whitman makes the audacious claim to be both the prophet and the messiah of a new American religion, in this passage from “Song of Myself" he adopts the more modest role of the poet-printer who constructs his book from discarded sheets of holy writ and then writes his poems as a palimpsest on the sacred past. Whitman counseled in the 1855 preface, “argue not concerning God.” His vision of a new holy book pieced together from the old ones provides a beautiful image of an inclusive future that respects its own past.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop