Every Atom | No. 84

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

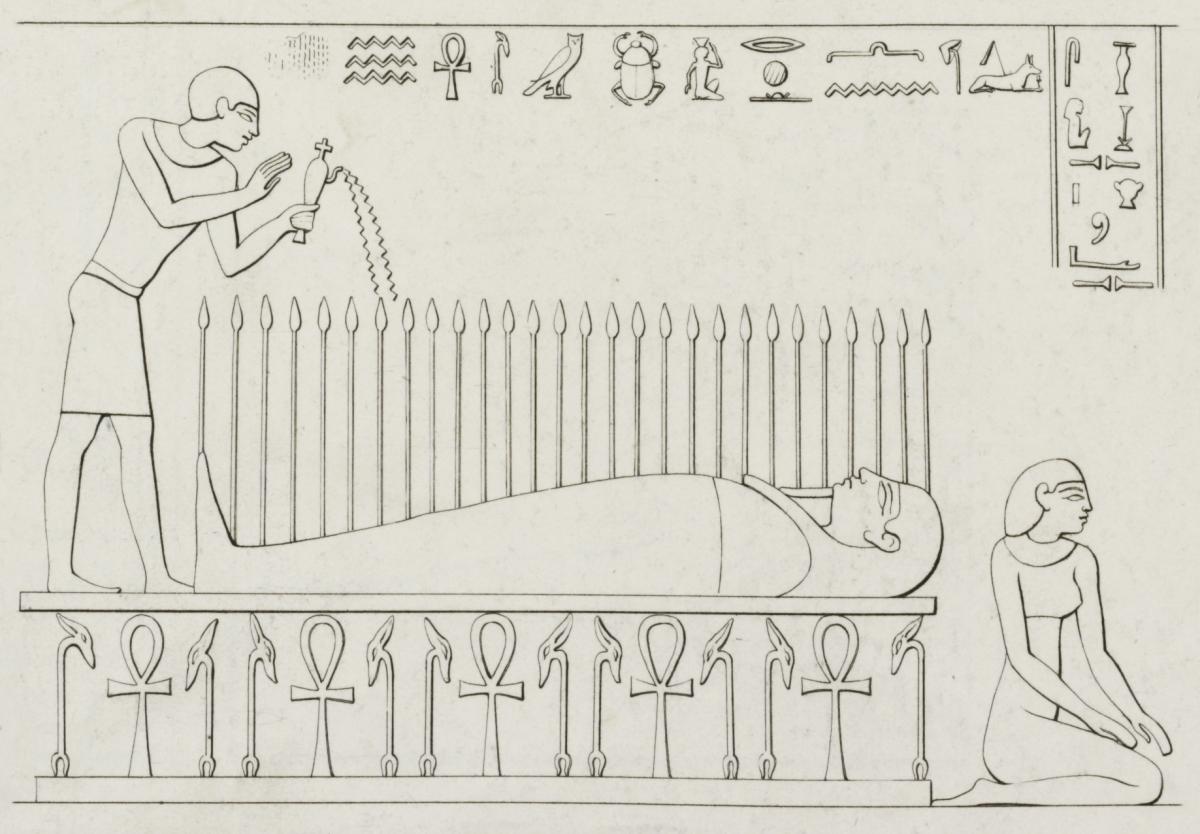

In the Astor Library in New York, sometime during 1855, Whitman came across a huge compendium of etchings of Egyptian hieroglyphs and tomb carvings that had been published fifteen years previously by an Italian archaeologist. One of these etchings, reproduced here, shows a version of the resurrection of the dead Osiris. A libation is being poured over Osiris’s coffin, out of which grow twenty-eight stalks of wheat. We do not know if Whitman studied this particular drawing, but it seems likely. In 1856 he published “A Poem of Wonder at The Resurrection of The Wheat” (later, “This Compost”), one of whose lines could serve as a caption for the drawing: “The resurrection of the wheat appears with pale visage out of its graves…”

The Osiris etching that Whitman probably saw in the Astor Library in 1855

There are many conflating accounts of the story of Osiris, but all agree on certain elements. Osiris was a god-king who ruled Egypt in ancient times. His brother, Set, jealous of his power, killed him by trapping him in a box and floating it down the Nile. Isis, who was both Osiris’s sister and wife, retrieved the body and brought it back to Egypt. Set found it again, however, and, tearing it apart, scattered the limbs. In some versions of the story, Isis gathered the limbs, put the body back together, and then lay with her husband to bring him back to life. In other versions, Isis took the form of a bird and flew over the earth seeking Osiris’s body. When she found it she beat her wings so that they glowed with light and stirred up a wind; Osiris revived sufficiently to copulate with her, begetting their son, Horus.

The etchings Whitman saw refer to a more vegetable version of the resurrection. Osiris was also a god of the crops, identified with the annual Nile flood and subsequent reappearance of the wheat. A number of reliefs have been preserved in which plants or trees grow from his dead body. In paintings and statues, Osiris is typically painted green. It was also the custom to make a figure of Osiris in grain on a mat placed inside a tomb. In the museum at Cairo there is an Osiris mummy which in ancient times was covered with linen and then kept damp so that corn actually grew on it.

Osiris is the “evergreen” principle in nature. Like the other well-known vegetation gods, he stands for what is broken, dismembered, and decayed yet returns to life with procreative power. His body is not just reassembled, it comes back green. With him we turn to the mystery of things that increase as they perish and the gift as a property that both perishes and increases. Osiris is the mystery of compost: “It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions.”

Adapted from Lewis Hyde’s The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World (Vintage 1979).

Image: “Rappresentanze della camera funebre di Osiride, relative alla sua morte e Risorgimento. New York Public Library Digital Collections. From Ippolito Rosellini, Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia, Vol. III (Pisa, 1844).

Full image can be accessed in the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Lewis Hyde is a poet, essayist, translator, and cultural critic with a particular interest in the public life of the imagination. In addition to The Gift, he is the author of Trickster Makes This World; Common as Air; A Primer for Forgetting; and a book of poems, This Error is the Sign of Love. He has also published two volumes of translations of Nobel laureate Vicente Aleixandre’s poetry and is the editor of On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg and The Essays of Henry D. Thoreau. A MacArthur Fellow and former director of creative writing at Harvard University, Hyde was the Richard L. Thomas Professor in Creative Writing at Kenyon College until his retirement in 2018. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his wife, the writer Patricia Vigderman.

Lewis Hyde is a poet, essayist, translator, and cultural critic with a particular interest in the public life of the imagination. In addition to The Gift, he is the author of Trickster Makes This World; Common as Air; A Primer for Forgetting; and a book of poems, This Error is the Sign of Love. He has also published two volumes of translations of Nobel laureate Vicente Aleixandre’s poetry and is the editor of On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg and The Essays of Henry D. Thoreau. A MacArthur Fellow and former director of creative writing at Harvard University, Hyde was the Richard L. Thomas Professor in Creative Writing at Kenyon College until his retirement in 2018. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his wife, the writer Patricia Vigderman.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop