Every Atom | No. 86

Introduction to Every Atom by project curator Brian Clements

In 1855, when the first edition of Leaves of Grass appeared, Walt Whitman was 36 years old, and yet the section later to be called “Song of Myself” ends with a first-person, present-tense rendering of his death as a white-haired elder. It is a sensuous death, a willed disintegration into the elements and literary history: “I depart as air, I shake my white locks at the runaway sun, / I effuse my flesh in eddies, and drift it in lacy jags.” And then he bequeaths himself to the dirt, to regeneration, and to our possibly bewildered reading of the poem he has just concluded.

Earlier, in the section to be labeled in future editions as part six, Whitman already had seen the grass as hieroglyphic, as something to be read, and then, suddenly, as “the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” Longing to “translate the hints about the dead young men and women,” he wonders what has happened to them. And then he knows

They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceas’d the moment life appear’d.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

“Song of Myself” is visionary and ecstatic; nevertheless, its description of death within nature’s cycles is scientifically accurate and spiritually challenging. And its trope of grass presents the central metaphor of the whole career. Certainly, Whitman’s experience of the war among sick, wounded, and dying soldiers in Washington, DC’s hospitals would deepen and darken this vision, but the metaphor would stand: death goes into the ground and life rises from it. And who is to say with certainty what the word “soul” may yet signify in our positivistic age and what the career of a self may really be? In “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” Whitman described the self as “struck” like a coin “from the float forever held in solution.” And in “Faces” he had imagined selves careering through time and lives toward a final perfection.

Spots or cracks at the windows do not disturb me,

Tall and sufficient stand behind and make signs to me;

I read the promise and patiently wait.

I held these passages in mind five years ago when I visited the Camden, New Jersey Whitman House where the poet lived from 1884 until his death in 1892. The last stop in our tour of the home, which has been restored to resemble its appearance when Whitman lived there, was the small back garden. Within the wooden fence that borders the yard are several trees, a modest area of grass, patches of dirt, and clustered hostas growing in the shade of the trees. There was not a lot to see, but much to imagine. Our guide was a large man in a ranger-green New Jersey State Park Service uniform, and when it was time to go, I paused.

“Would you mind if I pluck a couple of hosta leaves?” I asked.

“Okay,” he replied. “They grow back.”

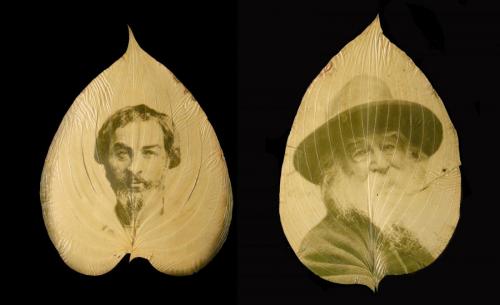

I had brought my materials with me. Back at the car on Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard (Mickle Street when Walt lived there), I placed the leaves on felt-covered boards, then covered them with plastic transparencies and sheets of glass. One transparency was printed with Whitman’s 1855 “Christ likeness,” the other with his 1877 “Old Philosopher” portrait, and when I clipped these layers together I placed the boards in the back window of the car where the sun poured down. As I drove north to visit friends on Cape Cod, the leaves began to change. Where the transparencies were clear the leaves bleached, and the portraits began to appear, embodied in the leaf’s sheltered pigments.

I had learned the chlorophyll print process from Binh Danh, its modern originator, with whom I’d been collaborating on a book of art and poetry. Binh’s leaves often hold the images of Khmer Rouge genocide victims, resurrected to peer out from their new green bodies to ask, “How could this have happened?” He hadn’t been thinking of Whitman, Binh told me, but they seemed to take the great war poet’s central image literally, conjuring presences in tropical leaves rather than leaves of grass.

And so, in a way, I was taking Whitman literally when I developed his portraits in leaves grown from his home dirt—or at least I was making a symbolic gesture, an art gesture—guided by his extravagant claims for selves and souls. If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles. So I did. Happy 200th, Walt. Every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you, wherever you are.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop