"Fighting Words: Fictional Struggles, Inside and Out"

I like to tell my students that every conversation is a fight.

Well, at least in fiction. In fiction, every character has a desire, and it’s usually the case that no two characters have exactly the same desire. It’s also usually the case that dialogue is not just talking—it’s a forum in which characters try to move the situation toward their interests. And if conversations are opportunities for characters to pursue their desires, which are not the same as what other characters want, then dialogue puts characters at active cross-purposes, with every line leaving them more at odds.

In other words, every conversation is a fight.

That’s certainly true in my story “Delicate Tables,” which first appeared in the North American Review and is now in my new short story collection, The Guy We Didn’t Invite to the Orgy and other stories. That book is full of fights, of course, mostly between people and groups—conflicts about belonging. (In one of the stories, there really is a guy who wasn’t invited to an orgy.) For its part, “Delicate Tables” takes on a particular kind of do-I-get-to-belong question: employment.

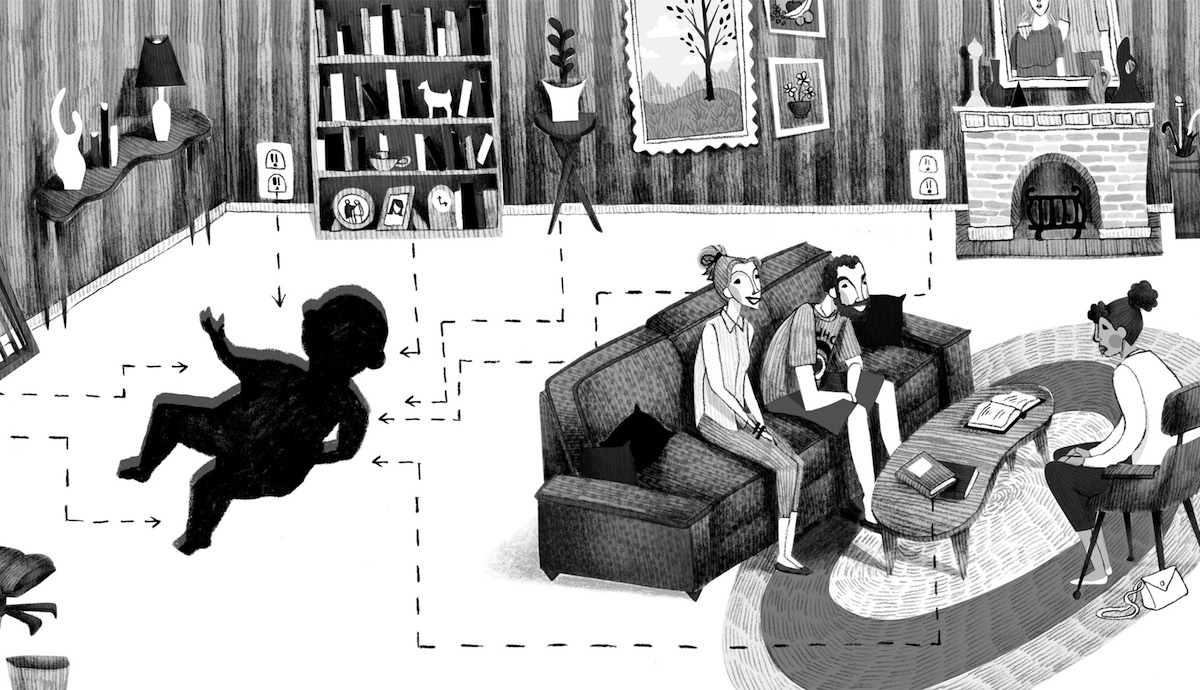

The story developed after I watched a couple of friends interview possible nannies. I was struck by the strangeness of the interaction. In theory, it could be a sort of cooperative thing; if all goes well in a particular interview, the person will be hired, which means they’ll be paid, and it also means that the two moms will be able to go back to their own jobs and their child will be in good hands; everybody wins. But of course these are interviews, and mostly they don’t go well, or at least not well enough for the person to be hired. My friends only needed one nanny, so they didn’t hire most of the people they talked to. And that inevitability was part of every conversation. The applicant knew she might not get the job, which would leave her unemployed, and the moms knew that the given person might not be right for the job, which would leave them still searching. There was lots of potential for disappointment on both sides—though of course the moms had more control than the applicants did; they got to choose.

That last aspect interested me a lot—the imbalance of power in the conversation. I think that’s why I ended up writing from the point of view of Neecie, an applicant for a nanny position, rather than from the point of view of one of the people in the couple who interview her. And I think it’s why the story gets a lot more complicated than the situation that inspired it. No spoilers here, but the man and woman searching for a nanny are not at all like my friends, and are in fact strange enough and difficult enough to inadvertently give Neecie more power; while she’s there, she thinks quite a lot about whether she even wants the job. That gives her some choice in the situation. At the same time, she really does need a job, and that makes it impossible for her to bolt after the first sign of trouble.

You see, characters have desires, sure, but a given character might have more than one, and those different wants might be at odds with one another. And that’s the second kind of battle—the inner conflict. On the one hand: “Neecie was half-tempted to just leave. She had another interview that day, didn’t need to stick around with these people….they were definitely off, and who needed that?” On the other hand: “But it just wasn’t in Neecie to leave things unfinished. And you could never count on the next interview working out; you always had to make this interview work out.” This internal battle interested me a lot, especially because I’ve certainly been in the position of needing a job and thus being stuck in the role of supplicant. It’s not fun.

Most fiction, if it’s really going to work, needs this. It needs multiple levels of conflict—between a character and the outside world (usually in the form of other people) and, also, within the character. And this layering is one of the ways that fiction can teach us about real life. Take my collection, for example. On the surface, it’s about the tension between individuals and groups (please let me into your group!), but ultimately it’s about something personal, something each person has to work out individually. Why do I feel like I don’t belong? Why do I want to belong? These questions probably won’t be answered if we’re granted membership in a club or social group. We have to get our own selves straightened out to answer them.

I won’t spoil things by saying how it all resolves for Neecie, but I think the internal battles are usually the most interesting ones. I mean, the external battles might be more obviously consequential—you get the job or you don’t—but the internal ones? Those are the ones that come with us wherever we go, the ones that follow us out the door once the conversations are over.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop