How Was "Eight Hours, with Cow" Born?

The first time I saw my father broken was a revelation. It was the morning after his multiple heart procedures at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Someone had propped him up in a mechanical chair, although his body had no strength, and he was slumped forward, chin to chest. Wires and cords slithered every which way, making me think of a puppet left abandoned in a closet. From there, my mind raced to Pinocchio, which was one of the first stories he told me when I was a child, and from there, to Indonesian shadow puppet plays, an art form I had taken to in my years spent living in Java, Sumatra, and Bali. The curious thing I discovered, standing in that room listening to my mother repeatedly ask my father—on the nurse’s orders—what year it was, was that my ever-present insecurity, my weakness in his presence, was intact. He was weak but still strong. Our relationship was as fraught as ever, quite beyond all the machines, beyond the heart that had been removed during his procedure and later replaced. I began to fear, listening to all the beeps and blips of his insides, that things would be exactly the same when he came back to himself. I feared that they wouldn’t.

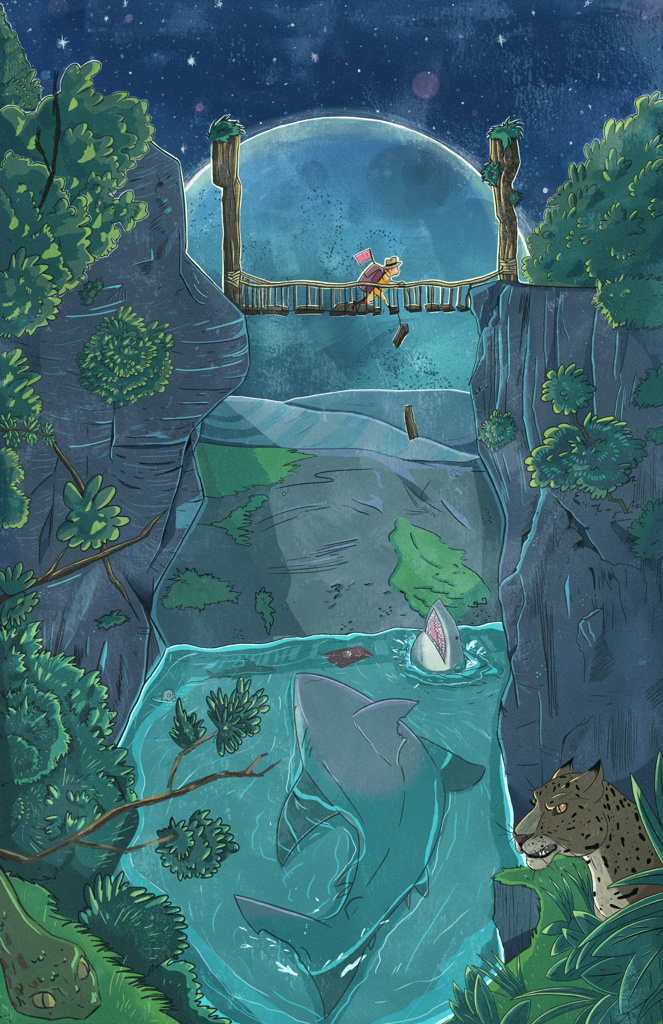

And this was how my essay “Eight Hours, with Cow” was born. I had been put in mind of the stories he told me as a child, using them as a kind of frame for the lyric structure. I also thought about the reasons why we never got along—his disappointment in my life choices—which include living and working overseas for years at a time.  For him, this choice means I don’t love him; for me, it means I am inspired to live out in the world because of the way he raised me. The cow part of the essay comes from the valve planted in my father’s chest, the idea that he had been remade as something more than himself, something sacred, something important.

For him, this choice means I don’t love him; for me, it means I am inspired to live out in the world because of the way he raised me. The cow part of the essay comes from the valve planted in my father’s chest, the idea that he had been remade as something more than himself, something sacred, something important.

I intended the piece to be an homage to my father and to the strange life of an itinerant writer. Living in so many places, although a strain on my family relationships, has put me in touch with a world of other stories. If I could communicate with him, even now, I would tell him these stories in the way he used to tell me his when I was a kid. But we never could communicate, so I keep them for myself, for this essay.

A quick note on craft. My love of the lyric essay style comes from such works as “The Fourth State of Matter” by Jo Ann Beard (more narrative than lyric, but the way she weaves her various strands is miraculous!), “The Pain Scale” by Eula Biss, “Son of Mr. Green Jeans” by Dinty Moore, Citizen by Claudia Rankine, and “Autopsy Report” by Lia Purpura. I feel like an essay concerning the jigsaw surgery that allowed my father’s heart to be removed and replaced demands a similar jigsaw format. The freedom of the form inspires, in that it slices and restitches narrative in unique ways. The trick, of course, is in making the disparate pieces form a coherent whole, which I think the examples above really do. As for my piece (which I in no way compare to the genius works above), once I hit upon storytelling, cows, and travel as strands, I was able to shuttle them back and forth over the heart of the story, which is my relationship with my father. By stitching it all together, my life, his surgery, the ways he’s motivated me, I have hopefully contributed to the genre of creative nonfiction generally while doing justice to him in ways he might not expect.

Someday I hope to show him this piece, which until now I’ve kept under wraps for the sake of his recovery. At least that’s what I’ve been telling myself. I suspect it has more to do with cowardice. I was never as strong as him, after all.

Recommended

Nor’easter

Post-Op Appointment With My Father

Cedar Valley Youth Poet Laureate | Fall 2024 Workshop