I Was From Where She Had Been From

When I was younger, the inability of strangers to guess where I was from satisfied my ambition to hide, to conceal, to cover up everything that had made me into who I was. Perhaps then I could convince myself that I was something else. However, after my mother’s death, I found no comfort in the fact that no one could guess I was from where she had been from, that I was from her. It seemed as if, in fact, it might not be true at all.

My mother was born in Jasper, right in the county where I grew up, but the relearning of this always came as a surprise because she did not grow up there. She spent her summers there at her Grandma and Grandpa Padgett’s farm, as did a menagerie of cousins. They would wake up to find biscuits in the kitchen and then would spend the day roaming the mountainside, Grandma Padgett fishing until time to cook supper and Grandpa Padgett working in the fields. I knew the names of some of the places my mother had lived: Flowery (pronounced “Floweredy”) Branch and Red Bud. When I was little, these places sounded mystically pretty. When my mother once attempted to drive me and my sister through one of these towns on our way somewhere else, it seemed like any other spot along the road, and it wasn’t the way she remembered it either.

I was born in the hospital in Canton, one county closer to Atlanta, and was brought home to the mountain where my mother had spent her summers. The land had been split among the brothers and the children of the sister, who had died too young. My grandpa had deeded a few of his acres to my mother and my aunt when my parents wanted to move back to Pickens County from Atlanta, where my father had been living and working when he met my mother.

I have a few memories of life in the trailer, on the mountain, most of them born of stories told and retold. The day they brought my sister home from the hospital, I demanded to be taught how to tie my shoes. No bus came for me the first morning of Head Start, and my mother raised Cain about the chigger attack I endured. We had a dog named Patches, who got his foot caught in a trap someone had set in the woods and had to be killed. A cat came and stayed that we called Tom until he had a litter of kittens. Then we called him Tomerina. We left him on the mountain when we moved, when I was in the first grade, into the house my father had lived in with his uncle and grandmother.

In the third grade, I learned I had an accent. I’ve since learned all Southerners have this story, in one iteration or another, eventually. I was telling my friend from Tennessee (the land of milk and honey, where she had been allowed to start kindergarten at age four) a story involving rurnt milk, and she kept asking me to repeat myself. Finally she pronounced, “Oh, you mean ‘ruined,’” and I felt something I now know to be shame. I began what I would now call a self-improvement project: I tried to sound more like my teachers and less like my family, to some success.

When I moved to California for college, I was delighted when person after person expressed surprise that I was from the South. I had successfully blended in in at least one way with the generic middle-class Americans I would keep trying to be. Of course, some things you can’t hide: the wide gap between my two front teeth, for one. I still wore the underwear I’d been wearing since I stopped growing: training bras and white cotton briefs with little-girl patterns. Eventually my mouth would betray me in other ways as well. There’s always a word or two you don’t get fixed.

Later, I went to writing school, and my first workshop teacher called my stories “suburban,” which, even though it was true, stung. When I had tried to set my stories in any location even approaching a resemblance to home, it felt staged and insincere, like I was an outsider playing at something. So I stripped my stories of setting or tried to set them, without naming them, in places like the Santa Monica neighborhood I had walked over my lunch hour before quitting my office job to go to writing school. For perhaps the first time, being mistaken for something I wasn’t felt annoying, uncomfortable, wrong.

Shortly before my mother’s death, I attended the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and there, among writers whose accents my own might’ve rivaled had it been left unabated, I felt like I wasn’t from anywhere. And hadn’t been in a long time. I had never been able to solve the problem of setting my stories anywhere in particular, and I wasn’t sure I had a right to. I regretted my earliest self-improvement project and burned with proper shame. Here’s the truth: I will never get back what I threw away.

I see other people from my county embrace it as an identity, and sometimes that seems right: they still live there. Sometimes they haven’t lived there any more recently than I have, and I wonder how they feel so at ease claiming this place that they’ve abandoned. Because isn’t that what I’ve done? I’ve left, got myself some education, and stayed away. I’ve come back to visit, I’ve seen the new restaurants, I’ve looked at the same blue mountains in the distance, the same tree-covered ones in the foreground, I’ve put my feet into the creek—but it’s not mine anymore, is it? And it feels presumptuous to say it ever was.

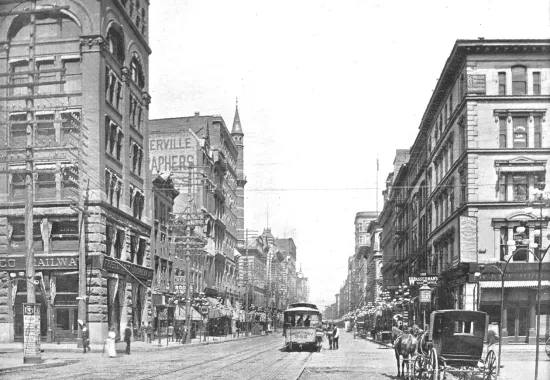

Illustration by Tom Moore, an illustrator who lives in St. Louis, MO.

Recommended

The Ballad of Ollie Jackson

A Picture of Stack Lee

Crossing Paths