On “I’m Like a Story Someone Told”

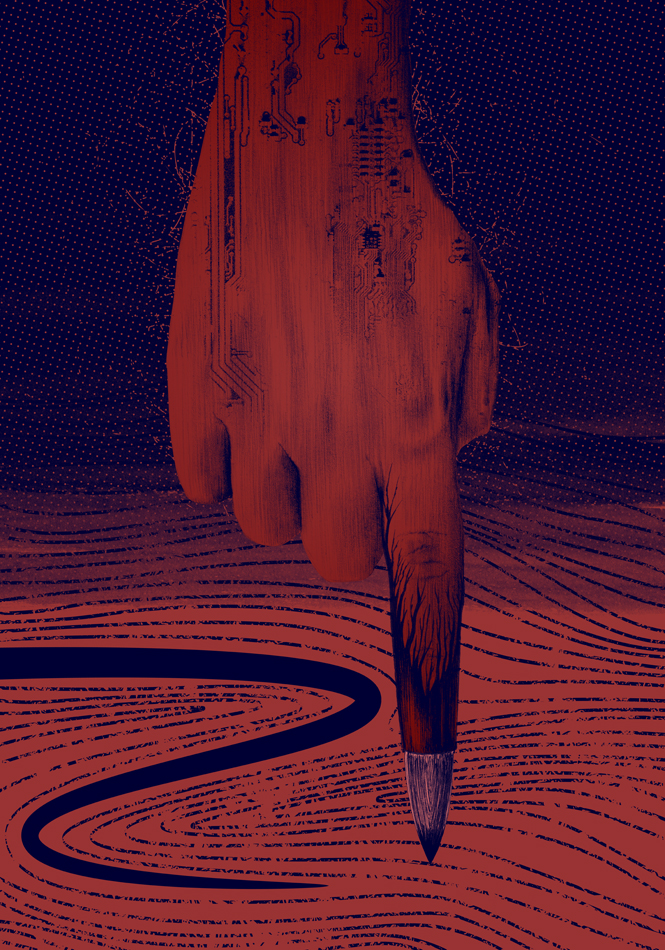

I came to writing late, starting at age thirty-four. My artistic life was born a month after my first child was born. I’m not fully conscious of the reasons for this. I only know that my writing often rises out of the dissonance between artistic and family life and that the poem included in the North American Review is no exception. Time is always the enemy. The need to spend time with my wife and children. The need to spend time with my work. And because time is limited, these two are often at odds. Over the years, I’ve learned to reconcile myself to the fact that there will never be enough time. But I’ve never fully reconciled myself to the fact that as a result of that shortage I will never really feel as if I’ve been good at either. I will always fall short of the ideal in my head. Telling stories to my children at night and the fact that those stories never quite come out the way I’d like them to, never quite match that movie reel in my head, embodies that failure, that disconnect between the ideal and the reality. The poem, “I’m like a story someone told,” tries to capture that feeling, but it also tries to capture the slippery nature of identity, the fictional quality of the character of any artist or writer who spends their lives trying to navigate between two worlds—the artistic and the familial. Anyone who has done this knows we spend so much time stepping back and forth between these disparate worlds, and at some point we simply can’t keep up appearances, we lose track of which world we are in, maybe we end up with a foot in each—the consequence being we don’t feel “real” in either.

I’m like a story someone told

I’m like a story someone told

It’s like the desperate whine of wheels stuck in snow, like trying to come up with an ending for the tales I tell my ten-year-old son in bed at night, tales of brigands and pirates, men who are proud of their plunder. No matter what I say, the ending falls short, and he wants another.

So I unravel again, neither of us any closer to listening.

Recommended

Mercy

Eclipsing

Psychic Numbing